Ryan Hass writes that the Biden administration’s approach to China reflects the acknowledgement that America must build ‘situations of strength’ with like-minded nations to respond to challenges posed by rival powers—a subtle but significant departure from the Trump approach to China. This piece originally appeared in the East Asia Forum.

In 1949, American strategists feared that Soviet advances were generating an intensifying threat to the free world. That August, the Soviet Union broke the United States’ nuclear monopoly by successfully detonating an atomic device. Washington worried that Moscow’s build-up of military forces could be a prelude to an offensive against western Europe and the Middle East.

In response, former US secretary of state Dean Acheson led an effort to formulate a government-wide response. The result was NSC-68, a strategy document that concluded that massive rearmament would be necessary to ensure the viability of the free world.

Acheson distilled his thinking in a 1950 speech at the White House, arguing that ‘The only way to deal with the Soviet Union, as we have found from hard experience, is to create situations of strength. Wherever the Soviet detects weakness or disunity—and it is quick to detect them—it exploits them to the full’.

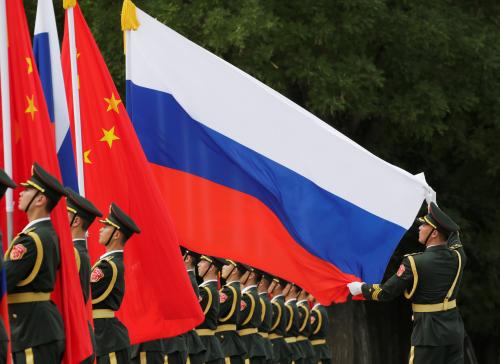

There are clear limits to historical analogies between the US–Soviet rivalry at the onset of the Cold War and the tense competition that exists between the United States and China today. Nevertheless, the core logic that Acheson articulated in 1950—that the United States must build ‘situations of strength’ with like-minded nations to respond to challenges posed by rival powers—is a central organising principle for how the Biden administration plans to compete with China.

This approach is informed by a judgment that, as in 1950, the United States and its main partners are aligned in support of important objectives—peaceful settlement of disputes, prevention of great-power conflict, promotion of an open and rule-based economic system, and the need for international coordination to tackle transnational challenges. Additionally, Washington and its main partners share broad interests in urging Beijing to forgo its bullying behaviour and accept greater responsibility for finding solutions to global challenges.

But alignment in support of common objectives will not automatically generate unity of effort. Unlike in 1950, when the United States produced 50 per cent of global output, every major economy in the world today maintains deep connections with China. As a result, no country is willing to join a bloc to oppose or contain Beijing. This reality will place limits on the level of unity that is available to contend with challenges posed by China.

To the extent that Washington proves able to collect the weight of key countries to deal with Beijing from a point of maximum advantage, it will be on an ad hoc, issue-by-issue basis. Countries will join the United States in seeking to influence Beijing based on their own priorities and how China relates to them. For some, the goal might be to push Beijing to halt its problematic behaviour. For others, it might be to press China to exercise greater leadership in addressing global challenges such as climate change.

To weave together issue-based coalitions, the United States will need to meet partners where they are, rather than demanding that they accept Washington’s perception of a China threat. Building common purpose with partners will not be exclusively animated by China. Rather, the guiding principle will be forging habits of coordination with friends wherever possible. With European partners, such efforts could work towards setting common climate change ambitions, which could then inform joint efforts to push Beijing to accelerate its timelines for achieving its climate targets. There also could be space for productive trans-Atlantic cooperation to accelerate technological innovation, shore up international trade and investment rules, combat the COVID-19 pandemic, uphold human rights and democratic values, and exchange best practices on countering domestic violent extremism.

With ASEAN partners, US policy might be tailored around the priorities of the region’s youthful and dynamic population. Specific projects might focus on expanding access to information and opportunity, developing human capital, demonstrating leadership on climate change or improving local public health capacity. Such efforts could pay dividends over time by elevating America’s appeal and creating a more fertile environment for coordination on specific issues relating to China. Attempting to mobilize the region to collectively push back against China’s maritime activities, by contrast, will have limited purchase. The United States must simultaneously allay concerns among partners about being ‘forced to choose’ between the United States and China. The inescapable reality is that China’s importance to other countries is growing. It is the world’s largest trading power and the leading engine of global economic growth. It is becoming more embedded in Asian and European value chains.

Given this reality, the United States will need to give allies space to pursue their own interests with China, even while they partner with the United States on priority issues. Washington will also need to demonstrate—through its own words and actions—that it supports developing a constructive relationship with China, even as it prepares to push back strongly against problematic Chinese behaviour.

Somewhat counterintuitively, the more Washington is seen as responsibly working to develop durable relations with Beijing, the more diplomatic space it opens for cooperation with others on China. Washington’s partners will feel more comfortable working with the United States on issues relating to China when doing so is not perceived as an expression of hostility towards China. When Washington is seen as an instigator of tensions with Beijing, on the other hand, it reduces partners’ willingness to work with the United States for fear that doing so could be perceived as tacit support for adversarial antagonism toward China.

Above all, Washington will need to right its own ship as a prerequisite for instilling confidence in its partners to join efforts to influence China. The United States must restore its own sources of strength by hastening domestic renewal, investing in alliances, re-establishing US leadership on the world stage, and restoring America’s authority to advocate for values.

The Biden administration’s approach to China reflects a subtle but significant departure from the Trump administration’s more direct approach of confronting China. Although the results of the Biden administration’s strategy may not be visible for some time, President Biden and his team do not harbour illusions of changing China overnight. They intend to play a long game. If their approach bears fruit, the United States will fortify its capacity to compete with China from a position of strength.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Biden builds bridges to contend with Beijing

March 15, 2021