Cars are a fact of life for the vast majority of Americans, whether we’re commuting to work or traveling to just about anywhere. But a new development outside Phoenix is looking to change that. Culdesac Tempe, a 1,000-person rental community, aims to promote a new type of walkable neighborhood by banning residents from driving or parking cars there. Instead, Culdesac Tempe will promote ride-sharing, biking, and other flexible transportation options (including a nearby light rail station) that will free up more land for open space and amenities.

For many Americans, the thought of giving up cars may seem impossible. But we know driving has plenty of negative health, environmental, and economic consequences. Our decision to drive is often one of necessity, as we contend with sprawling development that makes it hard to live, work, and interact in one location.

Culdesac Tempe is an important first step, but banning cars in a handful of neighborhoods won’t solve the larger transportation problem in metropolitan Phoenix and many other regions: the need to travel long distances to access economic opportunity.

Rather than focusing on an outright ban on cars, we need to make it easier for more people to live in places where shorter trips are the norm, and driving across an inefficient and inequitable built environment isn’t always necessary. Planners, developers, and other leaders need to invest in more connected, vibrant, and inclusive places that are designed around people, and reduce the distances we need to travel to get there.

Tempe: A sprawling city with long trips

Culdesac Tempe’s vision is commendable: supporting a dense, active community that aligns with changing transportation preferences and technologies. More people, especially younger travelers, want to walk, bike, scooter, or take transit rather than drive. Ride-sharing, car-sharing, transit upgrades, and other services offer greater flexibility. Even Waymo is testing driverless cars in the area. Culdesac Tempe aims to take advantage of all these conveniences in the rapidly growing area around Arizona State University.

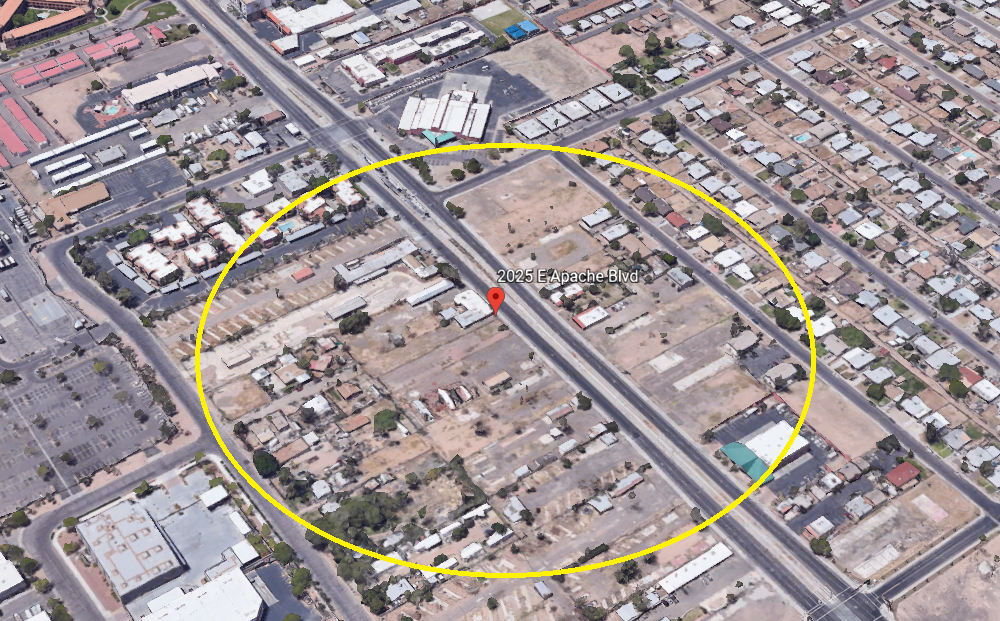

The challenge is that our transportation demands do not exist in a vacuum. While Culdesac Tempe’s proposed 16-acre community will have housing, shopping, and other amenities on-site, that doesn’t change the fact that the surrounding region is car-centric. Strip malls, parking lots, and warehouses are immediately adjacent to the project site. Residents will still need access to a car to reach distant workplaces, stores, schools, hospitals, and other destinations across the Phoenix metro area. This is a common concern that has stymied new urbanist communities for years.

Proposed site for Culdesac Tempe

Source: Google Earth, 2025 East Apache Boulevard, Tempe, AZ

Source: Google Earth, 2025 East Apache Boulevard, Tempe, AZ

Due to the surrounding urban sprawl, Phoenix residents’ local trips are already long. According to the latest Census Bureau data, 59% of the metro area’s 2 million jobs are more than 10 miles away from where residents live. This is true across America, as the distance between people and their jobs grows, underscoring the importance of local land use and development patterns. Consequently, residents face significant spatial barriers to economic opportunity—and car travel is the only choice they have.

Americans have more cars and drive more miles than ever before

Phoenix isn’t alone. Nationally, we’re stuck in a car-centric landscape, with developers, planners, and policymakers continuing to fuel more suburbanization, highway construction, and parking. And although jobs are concentrating in denser areas, the majority are still marooned in far-flung suburbs. The average American commute exceeds 10 miles, making cars the default option for getting to work and many other types of trips.

As a result, our car dependence continues to grow. From 2005 to 2018, the total number of vehicles increased from 196.6 million to 221.4 million—a 12.6% jump. That’s 25 million extra cars on the road and almost two cars per household, highlighting the magnitude of the national challenge at hand.

Last year, 55 of the country’s 100 largest metro areas had more vehicles per household than the national average of 1.82. Many of these areas were concentrated in the Southeast, Mountain West, and West, ranging from Birmingham, Ala. (1.96) and Nashville, Tenn. (2.00) to Denver (1.94) and San Jose, Calif. (2.06).

There are exceptions to this increase. Several metro areas in Florida have older populations who tend to drive less, and then there are transit-rich cities such as New York, which had the lowest vehicles-per-household, at 1.26. Phoenix stood near the national average, at 1.84.

Finally, we’re continuing to drive a lot, with vehicle miles traveled increasing each year. The country’s drivers now log 3.2 trillion vehicle miles traveled annually, up from 2.9 trillion in 2010 and more than double the 1.5 trillion miles in 1980. VMT per capita isn’t much better; we’re each driving almost 9,900 miles annually, up from a recent low of 9,400 miles in 2013 and 6,700 miles in 1981. While VMT fell during the recession due to declining incomes and rising gas prices, that trend reversed as the economy recovered.

We must rethink our places and not simply focus on banning cars

Our need to travel long distances and our dependence on cars speak to the enormous spatial barriers we face.

These trends are especially concerning compared to our global peers, who are embracing denser developments, car-free city centers, and a broader range of transportation options. European cities stand out here, from Barcelona’s “superblocks” planning effort, to Ghent’s pedestrian zone, to Copenhagen’s bicycle highways. Compare our nearly 10% gain in VMT since 2010 to the United Kingdom (1.4%), France (6.4%), and Germany (6.7%). Some countries even reduced their net VMT, including Denmark (-0.1%), Spain (-3.8%), and Finland (-9.7%).

Some positive changes are taking place in the U.S., though. The number of driver’s licenses issued has declined for some age groups as part of decades-long trends. For example, the share of 16-year-olds holding a driver’s license has fallen from 43.6% in 1987 to 26% in 2017. Traditionally seen as a sign of freedom, licenses no longer hold the same appeal to many of today’s digitally connected teens. Many households don’t even own a car either; in 2018, the share of zero-vehicle households stood at 8.5%, affirming the importance of transit and other transportation options.

So, while going car-free may be an impossibility for most Americans, that doesn’t mean some places aren’t changing.

Developments like Culdesac Tempe are part of a movement toward shorter trips, aimed at helping individuals benefit from greater proximity to economic opportunity via better transportation access, affordability, and choice. Human-scaled designs and projects focused on pedestrian access and connectivity are making a difference in cities across the country. The pent-up demand for walkable urban places is reflected in higher rents and higher GDP per capita in those areas. Parking minimums—the amount of parking legally required in new developments—are disappearing in cities such as San Francisco and Minneapolis. Congestion charges and additional parking permit fees have the potential to limit driving in New York. These efforts encourage people to drive less, while incentivizing the creation of more walkable, livable communities.

No single strategy, or development, will obviate our need to travel long distances. But plans focused on improving walkability and connectivity—across different neighborhoods and whole regions—should become the norm if we’re to address the inefficiencies and inequities in our legacy transportation systems.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Banning cars won’t solve America’s bigger transportation problem: Long trips

January 6, 2020