In advance of the Oct. 19 presidential debate at UNLV, The Sunday and the Brookings Institution, in partnership with UNLV and Brookings Mountain West, are presenting a series of guest columns on state and national election issues.

Every U.S. president since George Washington has had to deal with dangers abroad. Our nation’s chief executive is also our commander and diplomat in chief. That part of the job is going to be especially difficult for the president we elect Nov. 8, given the seemingly unprecedented multitude of menaces to U.S. interests around the world.

Not that President Barack Obama had it easy when he entered the White House in January 2009. He inherited wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, neither going well, and a severe downturn in the world economy as a result of an implosion in the U.S. real estate and financial sectors.

But back then, at least, the word “ISIS” had only two meanings — the Egyptian goddess of fertility and a tranquil river meandering through the English countryside; the Middle East, while far from tranquil, had yet to reap the whirlwind that began with the Arab Spring; Obama touted Turkey as a showcase of how secularism and democracy could thrive in a Muslim state; Dimitry Medvedev (remember him?) was the top man in the Kremlin, ready to reset U.S.-Russian relations; Ukraine was at peace within its own borders; the European Union was launching its “year of creativity and innovation”; France, ending a decades-long sulk, strengthened Western security by rejoining the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) as a full member.

Moreover, despite a largely hostile Congress, Obama has used his presidency to make significant progress on three high-stakes issues: constraining Iran’s nuclear ambitions, defrosting U.S.-Cuban relations and nudging the world toward a serious action on climate change.

Alongside the opportunity to build on those initiatives, Obama’s successor will have to grapple with threats that have gotten worse in the past few years. The Arab world is far more turbulent than it was eight years ago. North Korea’s dictator, Kim Jong-un, claims to be developing ballistic missiles that can reach the U.S., and that he has tested a hydrogen bomb.

Our 45th president will have to deal with the stark reality of a new cold war against Vladimir Putin’s expansive Russia, a more assertive and repressive China, a brutal civil war in Syria that has created a humanitarian catastrophe and, partly as a result, a European Union on the edge of what its own leaders call an existential crisis.

As for NATO, America’s closest ally, Great Britain, is going through what we can only hope is a passing phase of self-diminishment. Turkey — a strategically key member of the alliance — suffers from an increasingly authoritarian president, lethal problems with several states on its borders and an on-again/off-again affinity with Putin.

These are the regional specifics of what has become a worldwide contagion of heightened tension between nation states, upheavals in failed states and the spread of ungoverned spaces where terrorism tends to thrive.

International bodies like the United Nations are struggling. So are efforts at maintaining vigorous and healthy world trade. The aftermath of the Great Recession includes a backlash against globalization itself in the resurgence of protectionism rooted in the social and political pathologies of nativism and xenophobia.

These adverse trends add up to a reversal of the progress that characterized the second half of the 20th century and the first years of the 21st. Integration seems to be giving way to disintegration, order to disorder, cooperation to competition and conflict.

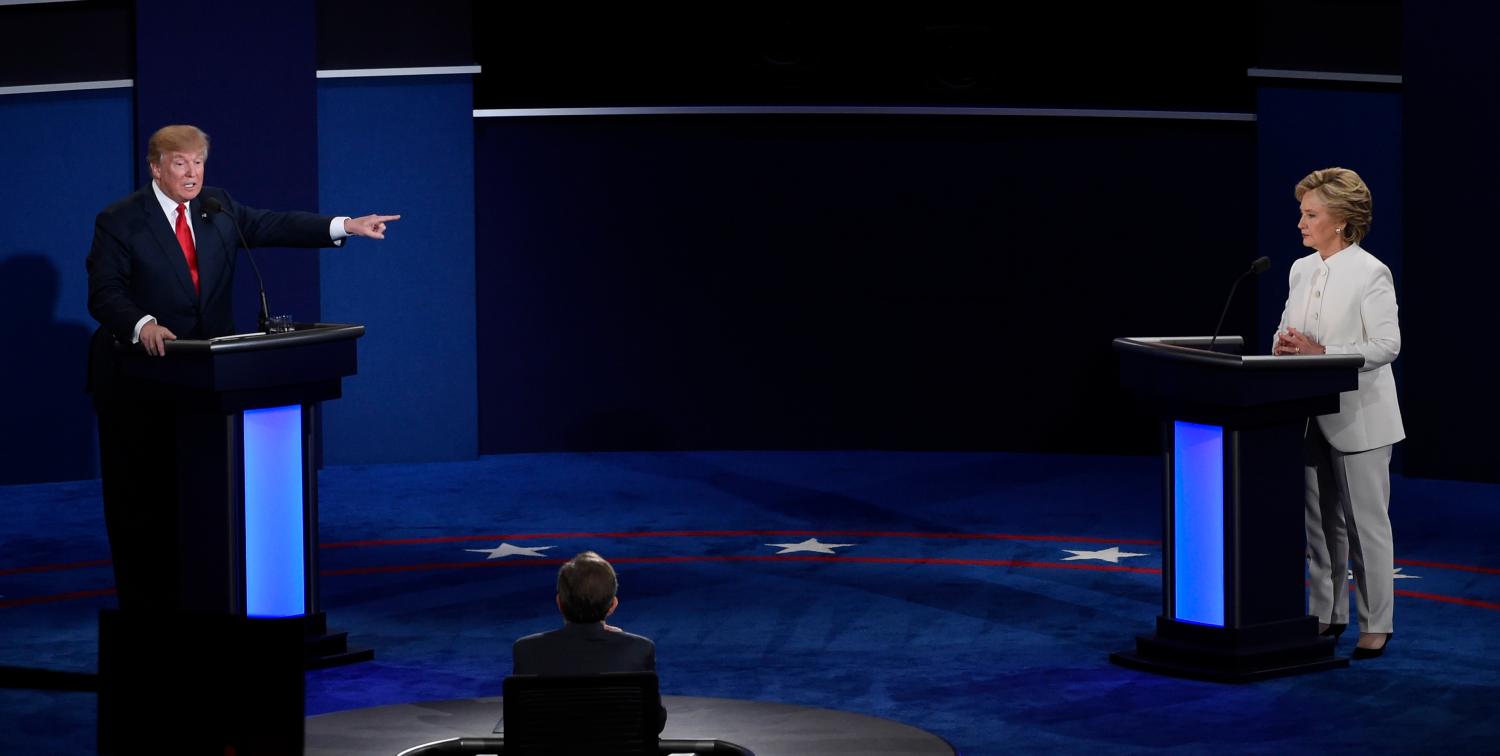

It’s no wonder Obama, only half-joking, asked last September, just before the beginning of the presidential election season, why anyone would want his job. But 21 major-party candidates — 16 Republicans and five Democrats — did. Now it’s down to Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, who are scheduled to debate Oct. 19 at the Thomas & Mack Center.

Here are some facts and factors to consider as citizens decide which candidate offers the most realistic and constructive vision for American foreign and security policy for the next four to eight years.

Let’s start by putting the current messiness and scariness of the world in historical perspective.

The bad news screaming from the headlines may seem pervasive, ominous and overwhelming. But it is by no means unprecedented.

Our leaders have faced constant challenges — some more dangerous than those today, others that have exposed the limits, failures and misuse of American power. Yet their legacy is a reminder that our nation, fallible as it is, has maintained a deep reservoir of resilience, adaptability, strategic continuity and a blending of idealism and pragmatism of which we can be proud.

While Theodore Roosevelt’s voice boomed from the bully pulpit, he believed in speaking softly while carrying a big stick, a motto for what today we call diplomacy backed by force. Woodrow Wilson kept America out of World War I for nearly three years, then switched course and intervened militarily, thereby ensuring victory. Franklin Roosevelt took the nation into World War II after the most devastating attack the U.S. has ever experienced and at a time when it looked like the Thousand-Year Reich and the Empire of the Rising Sun were well on their way to domination of much of the world.

Harry Truman, untested and unpopular, came to the rescue of a war-torn Europe that was flat on its back and menaced by a Soviet juggernaut, while dealing cautiously with mainland China as it fell under Communist control.

In 1956, Dwight Eisenhower, our only general-turned-president since Ulysses S. Grant, was determined to keep the Cold War from turning hot. He thought he had no choice but to rein in Britain and France, who joined Israel in an ill-advised invasion of Egypt, an ally of the Soviet Union. That was the right call, even though it meant humiliating two of the United States’ staunchest allies just as the Soviet army was crushing the Hungarian revolution.

During John F. Kennedy’s thousand days in the White House, he was in almost nonstop crisis mode. First came a U.S.-sponsored anti-Fidel Castro invasion that fizzled on the beaches of the Bay of Pigs, followed by two showdowns with Nikita Khrushchev over his bullying of West Berlin and stationing missiles in Cuba. Either one of those could have led to a thermonuclear war.

The Johnson, Nixon and Ford administrations were bedeviled by the grueling, divisive and ultimately futile war in Indochina. Yet they and their successors still managed to contain the USSR and Warsaw Pact until their demise in 1991.

This backstory should give Americans and our friends around the world confidence that the cumulative trials and perils awaiting the next president, serious as they are, are ones that our nation is up to.

The American economy is still the largest in the world, and its recovery is well ahead of those of most other advanced countries. U.S. armed forces, in both quantity and quality, are ahead of the arsenals of the next eight other countries combined.

The new administration will have to take extra measures to deal more effectively with regional powers that are breaking bad: Russia’s effort to extend its sphere of domination, China’s assertiveness against its neighbors and North Korea’s growing belligerence.

In addition to deterring real or potential adversaries, the U.S. will have to ratchet up its support for fellow democracies. While that’s a global imperative, it has now become a priority in Europe in the wake of massive refugee flows, the rise in identity politics, populism and, in several countries, secessionism.

Here again, though, history is on our side, and Europe’s. Over the past 70 years, with persistent backing from the U.S., Europe transformed itself from the most blood-stained of all continents into a zone of peace, prosperity, collaboration across borders and open societies within them. Repairing the EU’s flaws — such as the tensions created by a monetary union that’s not supported by a fiscal union, and addressing popular discontent with the EU bureaucracy in Brussels and the European Parliament in Strasburg — will require significant reform, political courage and, as before, unstinting U.S. support.

All that is doable if leaders on both sides of the Atlantic convince first themselves, then their constituents, that the European Project’s basic principles are solid, its troubles remediable and its survival essential.

The same cannot be said about Putin’s project. He has resurrected a zombie method of governing his country and, as he sees it, making it great again. He relies on repression at home, aggression and intimidation abroad, the Big Lie and a statist economy in which Kremlin-favored oligarchs have taken the place of commissars. That model, in its Soviet incarnation, failed before, and it will fail again. It will fail not, as Putin fears, because of a Western-instigated “colored revolution” but because the atavistic system he has reinstated has been proved not to work.

As for the Western response to Putinism, containment — accompanied by dialogue and diplomacy — worked before and would work again. In fact, it’s already working. Despite the fissures in Europe and the strains in the transAtlantic community, the U.S. and EU are holding firm on sanctions against Russian individuals and entities implicated in the annexation of Crimea and the occupation of eastern Ukraine.

Meanwhile, NATO has made some progress in recent months in protecting member states from Russian revanchism.

Like Russia, China has no real allies, only frightened neighbors. The U.S., by contrast, has 26 treaty allies in Europe, 22 in the Western hemisphere and six in Asia.

Managing the geopolitics of the 21st century depends heavily on healthy geoeconomics. That includes a world trading order that benefits all countries that participate — and, crucially, also benefits as many of those countries’ citizens as possible, particularly those who are economically vulnerable.

Therein lies an urgent and difficult task for next U.S. president. The Republican and Democratic primaries sent a clear message to the candidates for the White House and Congress: There’s a formidable disenchantment with trade agreements like the Trans-Pacific Partnership among 12 nations in the Americas and Asia, and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership between the U.S. and the EU.

The forces of globalization are a fact of life. Government policies can affect and channel them, but not stop or reverse them. The goal is to maximize and spread the benefits of globalization through international rules that ensure reciprocity and national safety nets for citizens who face losses in the short term.

In addition to looking to America’s past for inspiration as we debate policies for the future, candidates and voters should focus on a warning. When Teddy Roosevelt entered the White House, he quickly established himself as our first robust internationalist president. That was 115 years ago. For 95 of those years, the U.S. has been a major contributor to the progress of the human enterprise. But there also was a 21-year hiatus when our country failed in that regard. That was the isolationist era, starting with the Senate’s refusal to ratify America’s membership in the League of Nations in 1920. The U.S. turned increasingly inward. Ten years later, Congress enacted protectionist tariffs in the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, which, as has often been said, “put the ‘Great’ in the Great Depression.”

The lesson: Bad economics lead to bad politics that lead to bad policies, and sometimes war. The worldwide economic calamity played into the hands of hatemongering demagogues, notably Adolf Hitler, who used the rhetoric of ethnic cleansing, anger and vengeance to turn Germany into a militaristic police state. Still, the U.S. held back for another eight years, not lifting a hand against Germany’s annexation of Austria and the German-speaking parts of Czechoslovakia (sound familiar?). As late as September 1940, with Poland and France already under the boot of the Wehrmacht and Britain under Luftwaffe bombardment, Charles Lindbergh, Sinclair Lewis, Walt Disney and Teddy Roosevelt’s daughter Alice formed the America First Committee, which vigorously opposed intervention until Pearl Harbor 14 months later.

We must hope that the long spell of insularity was an aberration, never to be repeated. It took a catastrophe visited on the U.S. itself to shake our country back, belatedly but decisively, into 75 years of uninterrupted global engagement and leadership under 13 presidents, seven Democrats and six Republicans.

The years — and, indeed, the months — immediately ahead are an inflection point. The international situation is not just messy and scary, it’s unstable. Whether it gets worse or better depends in no small measure on whether the American people choose a leader for our nation who is committed to leadership of our world.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

As threats increase, America needs a diplomat in chief

August 22, 2016