The summer season typically brings with it a notable uptick in gun violence in cities across the U.S. But the stakes to reduce that violence are especially high this year. After a sharp pandemic-era increase in gun violence and tense local elections dominated by issues of crime and safety, local public officials are facing immense political pressure to advance effective and lasting solutions to keep their constituents safe.

At the same time, local leaders are confronting another important, albeit far less noticed task: determining how to budget the remainder of the American Rescue Plan Act’s (ARPA) Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (SLFRF) before the 2024 deadline. The SLFRF program—designed to provide fiscal relief for local governments to recover from the pandemic—also equips local leaders with unparalleled federal resources to address the pandemic-era spike in gun violence and lay the foundation for longer-term, root cause violence intervention strategies that can improve both public safety and community well-being. Indeed, last year, President Joe Biden urged local leaders to dedicate more of their ARPA dollars to violence intervention, and to do so swiftly to meet the urgency of the challenge.

Yet, early reporting by the Marshall Project on SLFRF allocations indicates that large local governments have mostly leaned on status-quo carceral public safety approaches (such as police, courts, and corrections) in the program’s first year. As many have pointed out, this could be a missed opportunity for cities and counties to invest in root cause community safety infrastructure (such as place-based safety programs in the economic, built environment, or public health domains) that not only improve long-term safety and well-being outcomes, but also reduce capacity constraints on the police.

To understand local spending patterns on community violence intervention—and, importantly, how local governments may be advancing root cause safety approaches with their SLFRF allocations—this brief provides new analysis on how cities and counties with populations over 250,000 (referred to as “Tier 1”) are using their federal dollars to invest in community violence intervention (CVI).

What are ‘root cause interventions’?

Root cause community violence interventions are evidence-based, community-centered, and multidisciplinary strategies designed to address the structural factors that contribute to gun violence, including interventions to prevent and disrupt cycles of violence, address trauma, enhance economic stability and opportunity, and improve the overall physical, social, civic, and economic conditions that contribute to violence. In addition, this brief defines “root cause” community violence interventions as explicitly non-carceral—i.e., those that do not involve law enforcement, the court system, or criminal detention. While carceral interventions are eligible uses of SLFRF dollars, they have long been the default response to addressing crime concentration and have received the vast majority of local public safety funding for many years. Instead, this brief focuses on strategies designed to pre-emptively transform the conditions that create and sustain community violence, rather than reactive strategies that address the symptoms of those conditions.

ARPA provides local governments with an opportunity to address gun violence while building lasting community safety infrastructure

ARPA funding was designed to promote inclusive and equitable recovery efforts in communities disproportionately impacted by the uneven effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. So, some may ask, what does pandemic recovery have to do with gun violence, and why do root cause approaches deserve specific attention? A review of the evidence indicates three key reasons:

- The same communities disproportionately impacted by the pandemic’s public health and economic effects bore the brunt of its uptick in gun homicides. Within cities, gun violence has long been concentrated in a select set of economically and racially segregated places where other indicators of disinvestment and structural disadvantage cluster. These same communities were hit hardest by both the pandemic and recent rise in gun homicides, while better-resourced communities were shielded from the worst effects of both. ARPA funds explicitly recognize that much of the same community infrastructure that contributes to positive public health outcomes—such as stable housing, living wages, and urban greenery—also contribute to positive public safety outcomes.

- Despite receiving the vast majority of funds devoted to public safety in regular budget cycles, status quo interventions haven’t produced lasting public safety outcomes. For the past several decades, the default response to addressing the intersection between place and violence has been to police the markers of place-based poverty further through carceral strategies such as predictive policing, “broken windows” policing, “stop and frisk” policies, and place-based policing units. Over time, carceral interventions can produce negative consequences for residents of these communities, including family separation, childhood trauma, reduced trust in the police, and even increased participation in illegal behavior. These status quo responses can not only be less effective than non-carceral alternatives, but they also only address the symptoms of neighborhood violence, rather than transforming the conditions that create and sustain it. ARPA provides local leaders with the opportunity to leverage federal investment to scale proven models that can improve safety outcomes without negative collateral consequences.

- ARPA dollars provide an unprecedented—and time-limited—funding source for root cause safety approaches with numerous community benefits. Even scholars who recognize role of police in deterring violence have found that U.S. cities are missing the opportunity to advance sustained, large-scale investments that change the very neighborhood conditions that lead to high violent crime rates in the first place. Intentional and targeted root cause approaches have never been given the chance to work at scale because they have never received even a fraction of the investment that punitive approaches have. ARPA allows cities and counties to alter this funding landscape for a limited period, providing them with federal dollars to advance root cause safety approaches while also producing positive benefits that reach beyond violence reduction to support healthy and thriving communities.

Methods

This brief provides an updated quantitative analysis of previous Brookings research on the use of ARPA dollars to address the root causes of gun violence—presenting the most recent snapshot to date of large city and county1 “community violence intervention”2 allocations and expenditures. It draws from quarterly reports submitted to the U.S. Treasury Department for data through December 31, 2022.

To better highlight different uses of CVI, this brief categorizes CVI projects into seven evidence-based categories: 1) economic programs; 2) built environment and neighborhood physical improvements; 3) social cohesion and conflict mediation models; 4) community nonprofit capacity-building investments; 5) trauma and victimization services; 6) behavioral health supports; and 7) carceral interventions, including investments in law enforcement, surveillance equipment, courts, and detention centers. (For a further explanation of which programs fall into the seven categories, please see the Glossary at the end of the brief.)

Importantly, there are two primary limitations to using the “community violence intervention” filter to understand SLFRF allocations to community safety. First, many funded SLFRF projects not coded as community violence intervention can still have an outsized impact in reducing violence. Second, the CVI category itself is a difficult allocation category to assign due to its interdisciplinary nature. Despite these limitations, this brief uses the CVI filter because it is focused on how local governments are explicitly thinking about community safety.

SLFRF dollars classified as “revenue replacement” are excluded in all comparisons of CVI to other SLFRF appropriations, obligations, and expenditures in this brief. The SLFRF revenue loss provision allows local governments to categorize at least $10 million of their allocation as “revenue replacement.” These funds are exempt from many of the use restrictions, program income requirements, and procurement conditions imposed on other SLFRF appropriations. Projects categorized under the revenue loss provision cannot also be classified under a second use category (such as community violence intervention) even if the recipient plans to use those funds for such a purpose. Therefore, because the CVI category must exclude revenue replacement dollars, these funds are excluded from comparisons against other use classifications as well.

Finding #1: Relatively few local governments are investing SLFRF dollars in community violence intervention

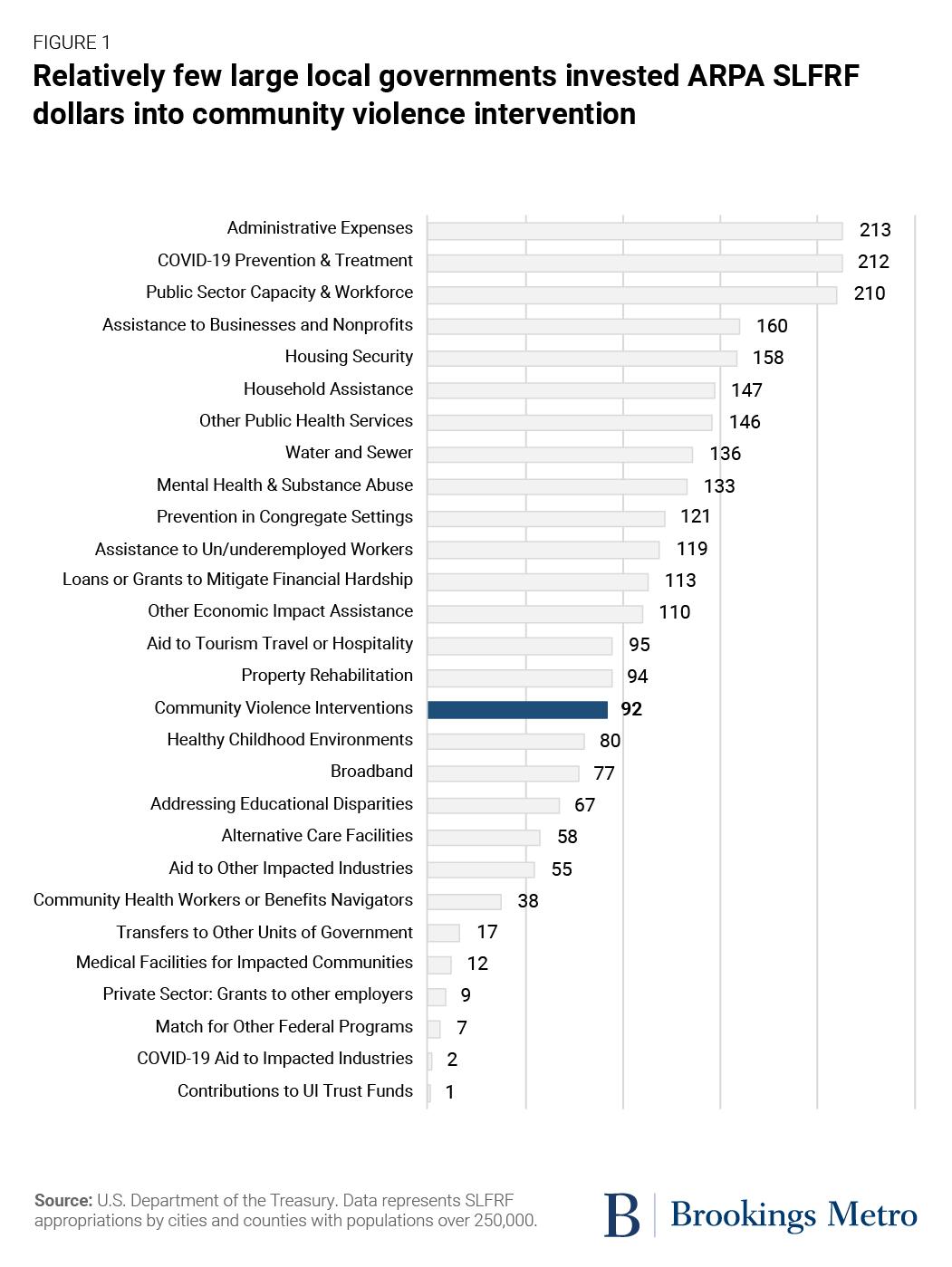

Of the 331 Tier 1 local governments that submitted reports to Treasury in December 2022, only 92 (28%) have used the SLFRF program to stand up or expand CVI initiatives in their communities (amounting to $683.7 million). While CVI is not the least-employed use of SLFRF dollars, it ranks substantially behind other categories that seek to address socioeconomic and community well-being disparities (Figure 1).

Finding #2: Of large cities and counties investing in CVI, the majority (69%) of root cause investments come from only five local governments

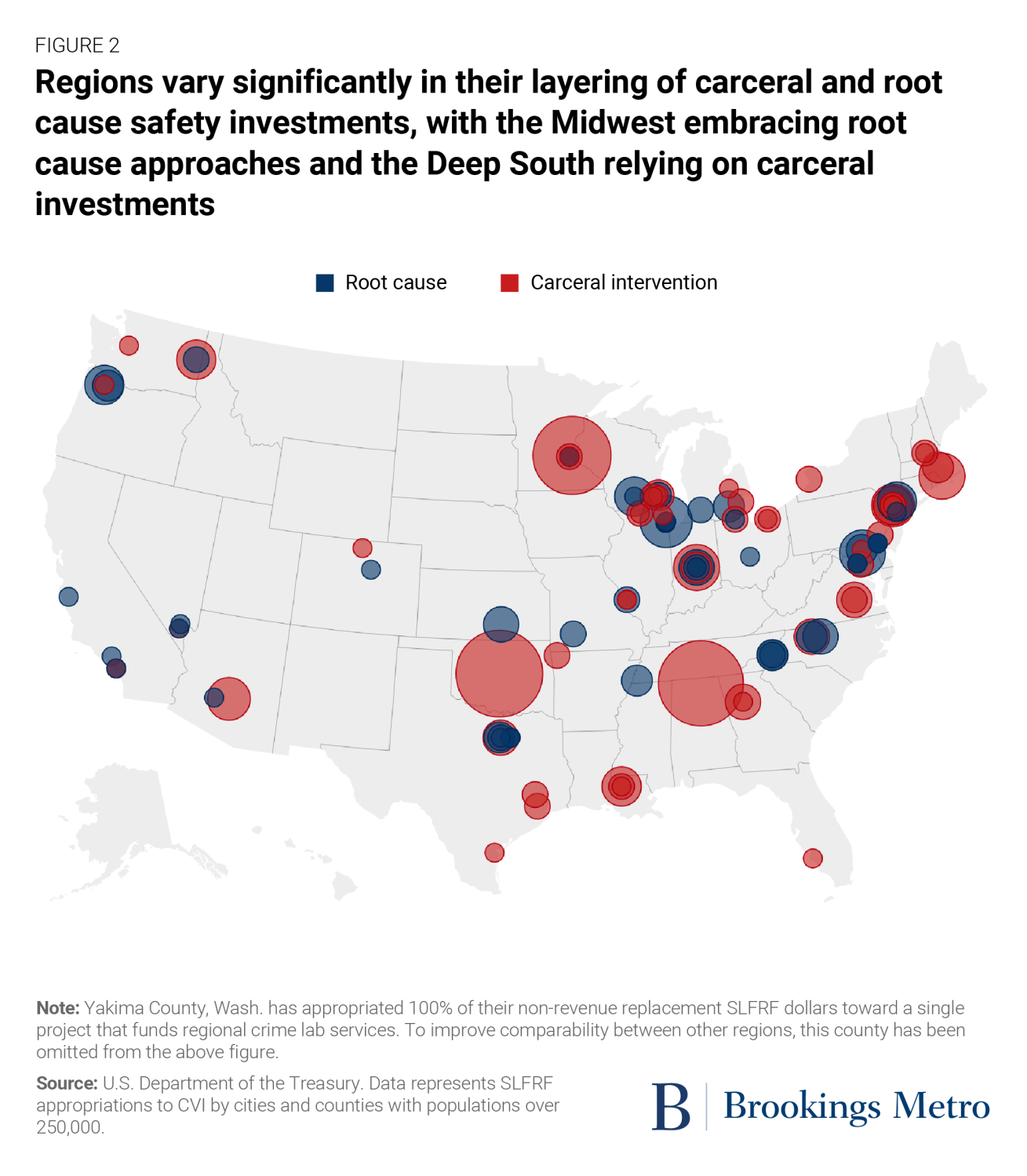

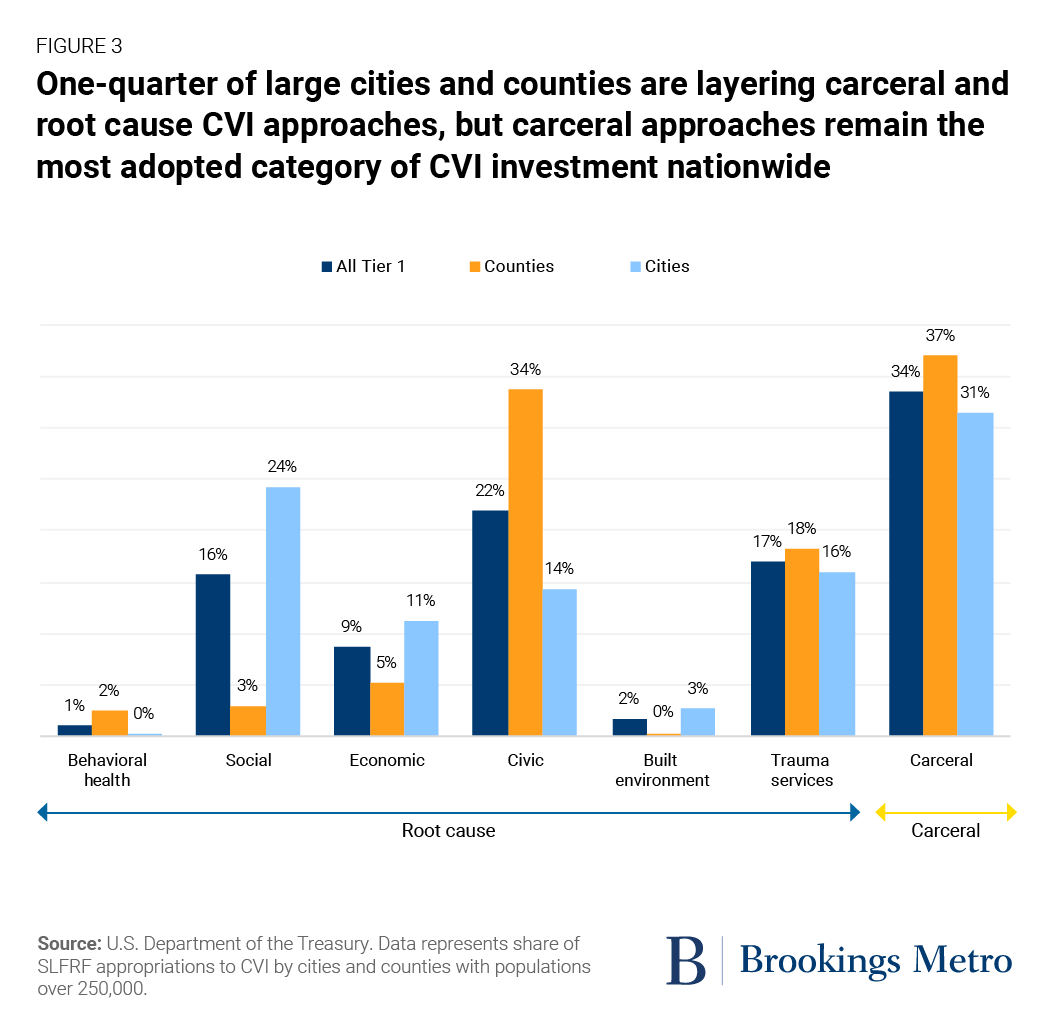

Among the relatively low number of 92 Tier 1 cities and counties investing in CVI, 65% of them have invested in root cause CVI approaches, 74% in carceral approaches, and around a quarter (26%) are layering both carceral and root cause approaches (this includes 35% of cities and 21% of counties). Cities and counties across the Midwest are spearheading this “layering” strategy, which is notably absent across the Deep South, where no large local government in Florida, Georgia, or Alabama has appropriated any of their SLFRF allocations to root cause violence intervention (Figure 2).

Importantly, trends in root cause CVI investments are heavily influenced by very large investments in a select few cities and counties. Of the 92 large local governments investing in CVI, the majority of appropriated funds (53%) are in the city of Chicago, Cook County, Ill., Washington, D.C., the city of Baltimore, and the consolidated government of Indianapolis (Marion County). Looking only at root cause CVI investments, these five local governments comprise 69% of all Tier 1 city and county investments in root cause interventions.

Our findings indicate that $453.8 million (66%) of the $683.7 million SLFRF dollars invested in CVI have been appropriated to different categories of root cause interventions. While at a glance this may appear to indicate a large-scale embrace of root cause approaches, the aforementioned five local governments responsible for the lion’s share of CVI commitments heavily skew these numbers. Across the board, carceral strategies have outpaced commitments to each type of root cause intervention by over a 10-point margin (Figure 3). Put another way, the average project using SLFRF dollars to fund carceral strategies accounts for 4.0% of that local government’s total non-revenue replacement appropriations, compared to just 1.8% per project for root cause interventions.

However, some large local governments are breaking this pattern. For example, Washington, D.C. invested only in root cause interventions under the CVI category (instead of layering carceral and non-carceral interventions), representing 6% of its non-revenue replacement appropriations.3 The city of Baltimore, which invested over 7% of its non-revenue replacement appropriations to date in root cause violence interventions, is scaling up its Mayor’s Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement to fund youth justice and “community healing” initiatives for residents impacted by gun violence. Chicago also represents an illustrative example for distributing large investments across multiple non-carceral root cause approaches to community safety (see text box below).

Chicago’s holistic approach to investing in CVI with SLFRF dollars

Chicago exemplifies how local governments can make large-scale investments in multiple non-carceral CVI approaches. The city stands out for appropriating 17% of its non-revenue replacement dollars to 16 root cause CVI programs, with focus areas spanning from youth supportive services to rapid rehousing to capacity-building. Notably, Chicago made large-scale investments in citywide community safety infrastructure, budgeting nearly $19 million to its Community Safety Coordination Center, which seeks to break down siloes and bring together health care, social services, education, restorative justice, faith, business, and other community partners with government partners to effectively scale CVI projects. Chicago also was one of the few cities nationwide to recognize the potential of built environment and place-based safety programming, appropriating nearly $10 million to improve infrastructure and create safe community spaces in areas of the city most impacted by violence.

Finding #3 Of large local governments investing in CVI, counties have embraced capacity-building projects while cities have focused on social cohesion and conflict mediation

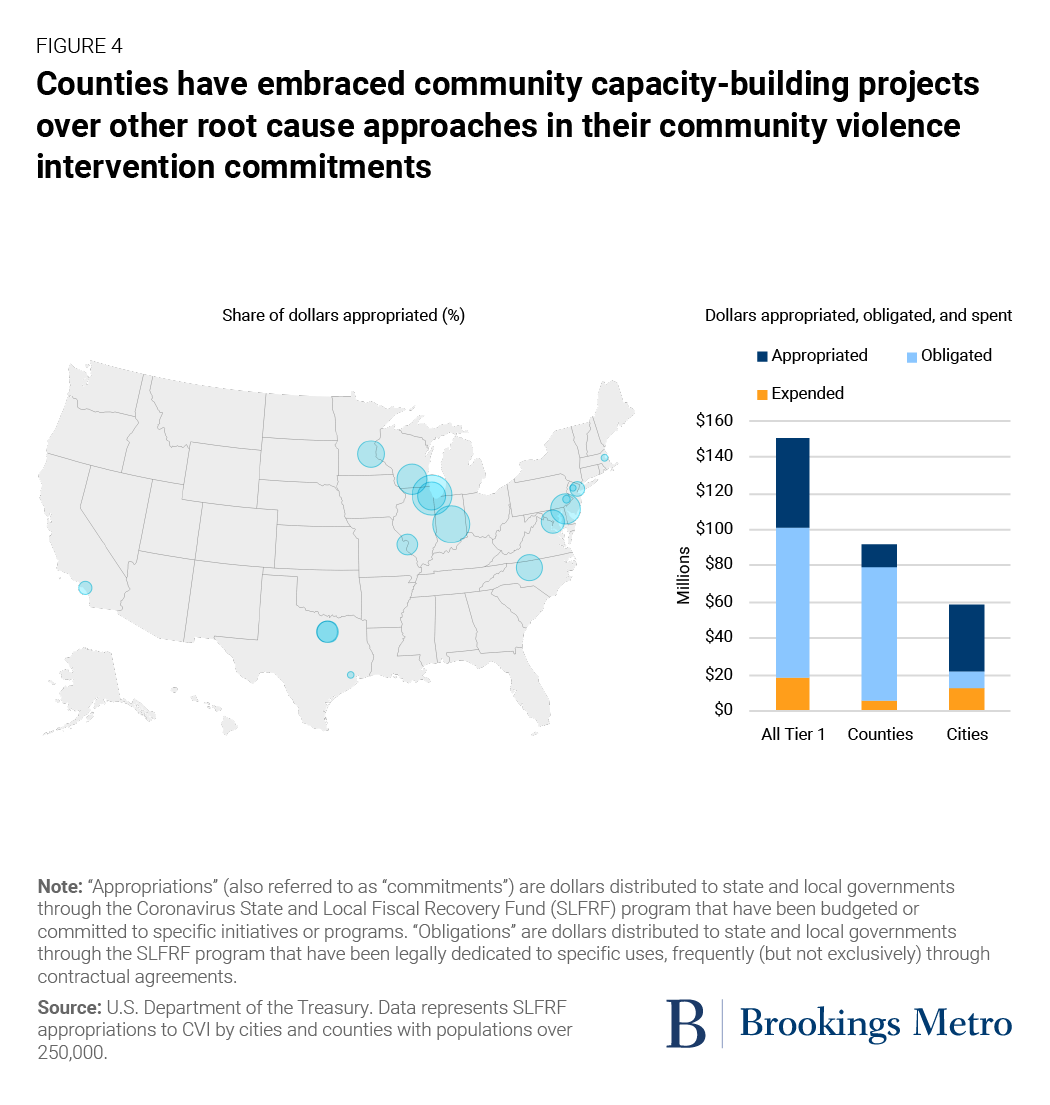

Counties have committed 34% of their CVI appropriations to civic capacity-building projects, outweighing their investments to other root cause interventions by a 16-point margin (though still lagging slightly behind investments in carceral approaches). This embrace of civic capacity-building as a CVI strategy is particularly notable in the Midwest and Northeast Corridor (Figure 4).

‘Strengthening community’ as a safety strategy in Tarrant County, Texas

Tarrant County, Texas (home to Fort Worth) provides a promising example for how a county in a region that has been slower to adopt root cause approaches (the South) is investing in civic capacity strategies to promote safety. As part of its “Strengthen the Community” approach, the county has appropriated $4.6 million to fund CVI strategies targeted to its highest-need communities, including a “Center for Transforming Lives” aimed at closing economic gaps for low- to moderate-income households.

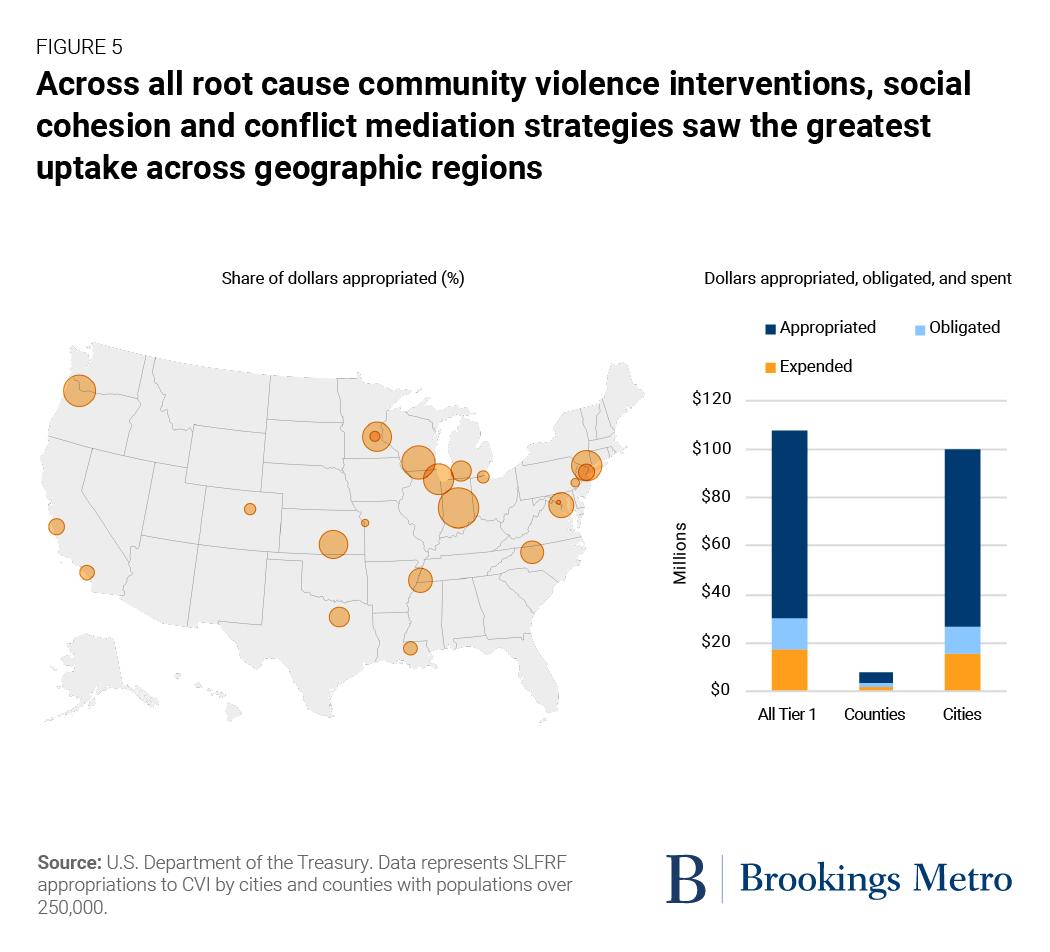

In contrast, cities have committed only 14% of their CVI appropriations to civic capacity–building, choosing instead to focus on economic support as well as social cohesion and conflict mediation programming (such as violence interrupter and credible messenger programs, mentoring initiatives, and other pro-social activities designed to improve safety). Interestingly, of all categories of non-carceral CVI approaches, social cohesion and conflict mediation saw the greatest uptake in cities and regions across the U.S., from Portland, Ore. to Memphis, Tenn. to Rockland County, N.Y.

Social cohesion and safety in Portland, Oregon

Portland, Ore. stands out from other Tier 1 cities for its embrace of social cohesion and conflict mediation CVI investments. (Figure 5). The city’s primary root cause intervention—Upstream Services for Families Impacted by Gun Violence—budgets over $11 million (7% of its total non-revenue replacement appropriations) to reduce violence in communities that have experienced dislocation and isolation during the pandemic (with a particular focus on African immigrant communities) by funding pro-social activities for youth and families.

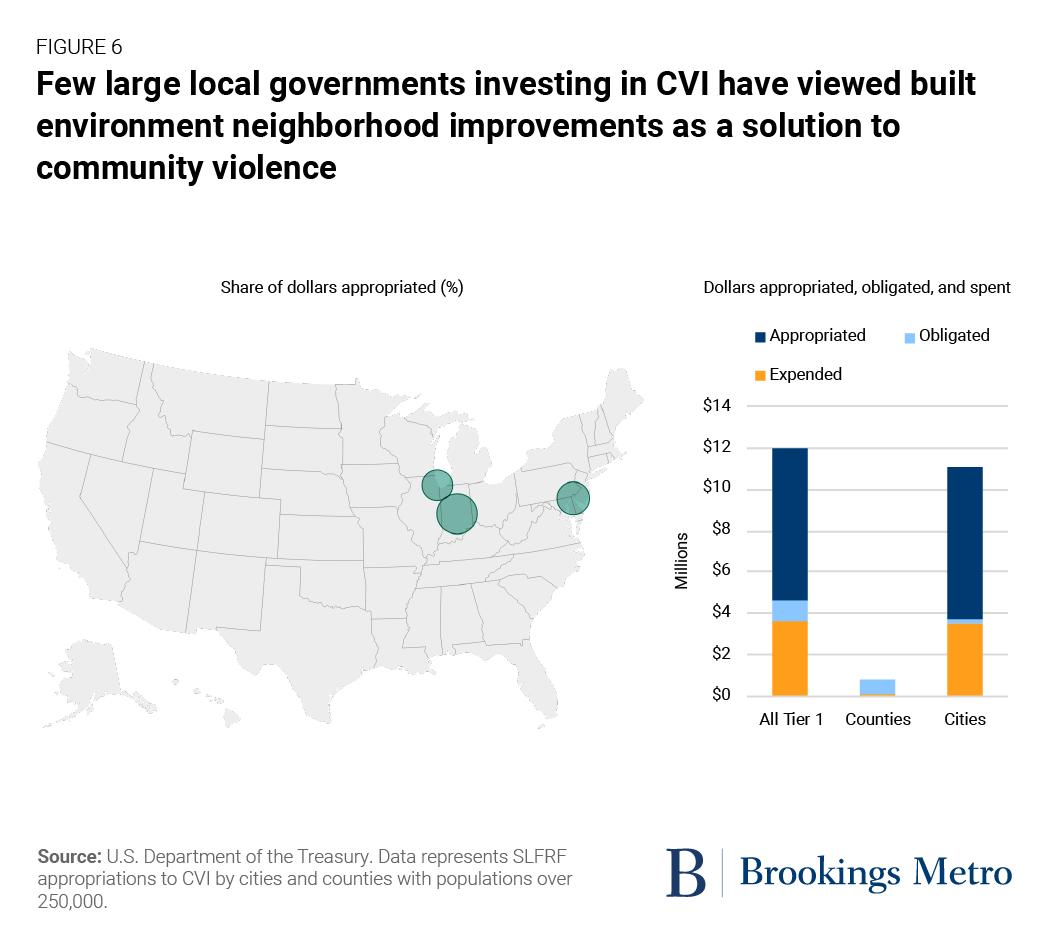

Finding #4: Despite sizeable investments in infrastructure, cities and counties have been slow to recognize the built environment as a tool for violence prevention

In recent years, the evidence base on the promise of built environment and other neighborhood improvements (such as vacant lot clean-ups, beautification efforts, and environmental design) to significantly reduce gun violence in the short and long term has grown. However, though cities and counties have made sizeable SLFRF investments in infrastructure (9% and 13% of their totals, respectively), most have not categorized these investments as violence prevention strategies. As of December 2022, only three large local governments have committed funding to built environment strategies under Treasury’s CVI classification: Chicago, Indianapolis, and New Castle County, Del.

Neighborhood beautification for safety in Indianapolis

One promising example of a built environment safety strategy is Indianapolis/Marion County’s Neighborhood Beautification Grants, which budget $1.1 million for ZIP codes that have experienced disproportionate axes of disadvantage (such as health disparities, high unemployment, and food insecurity) to invest in neighborhood-driven projects that nurture social cohesion and a sense of community. In total, 24% of local non-revenue replacement appropriations have gone to CVI, and 11% of those to root cause interventions (including the beautification grants).

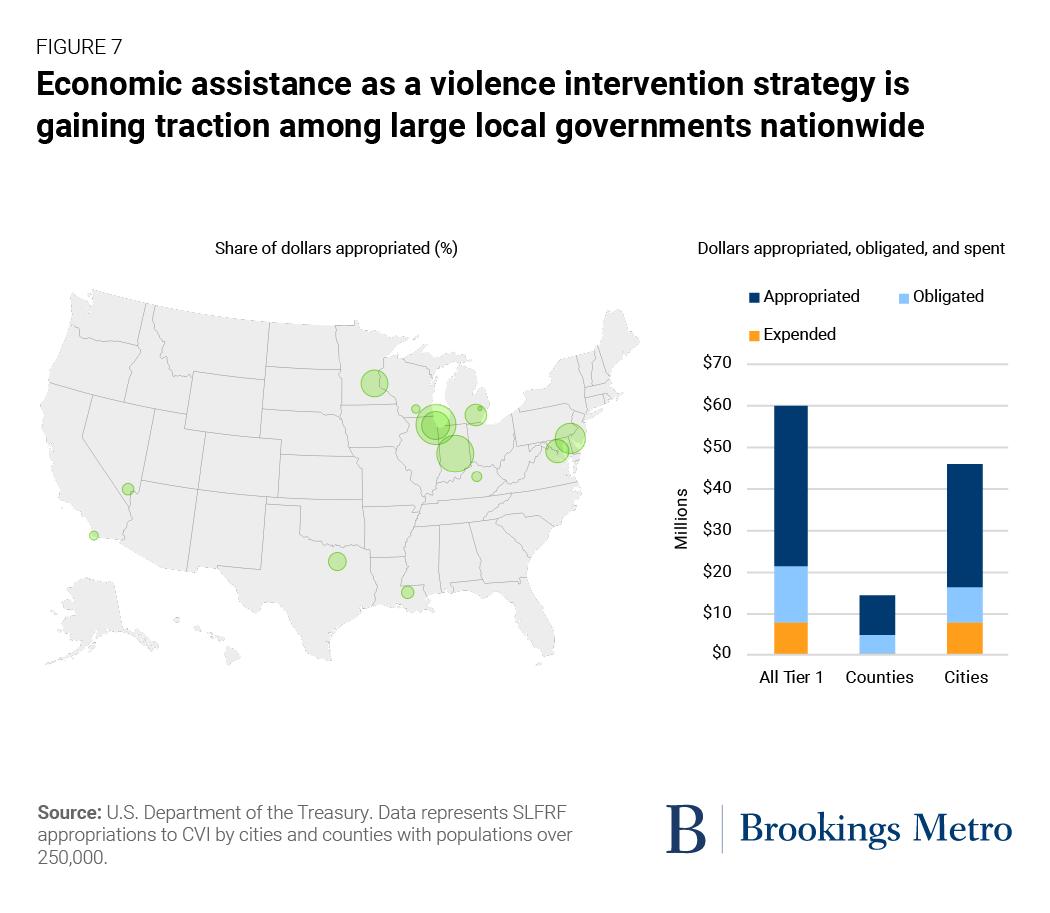

Finding #5: Economic assistance is gaining recognition as a violence intervention strategy, even when many of these programs have their own reporting categories

Roughly 9% of SLFRF dollars appropriated for CVI over the past two years have been committed to economic assistance projects (such as workforce/jobs programs, financial assistance, literacy training, housing and rental assistance, and reentry services), despite many of these programs having their own explicit reporting categories outside of CVI. This represents a notable difference in how cities and counties understand economic security as a nontraditional root cause approach to violence prevention compared to built environment investments.

Economic stability and safety in the mid-Atlantic

Two nearby mid-Atlantic cities exemplify the uptick in economic-based safety programs. In Baltimore, the Reducing Violence through Job Training Assistance program allocates over $10 million through the Mayor’s Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement to transition justice-involved individuals into employment. And in Washington, D.C., the Temporary Safe Housing for Victims/Persons At Risk of Gun Violence program allocates nearly $8 million to establish emergency housing for residents at risk of gun violence. While neither provide anything close to the full economic support needed to stabilize communities exposed to gun violence, they demonstrate promising examples of how city governments can follow the evidence to make meaningful investments in jobs and housing as a viable community safety approach.

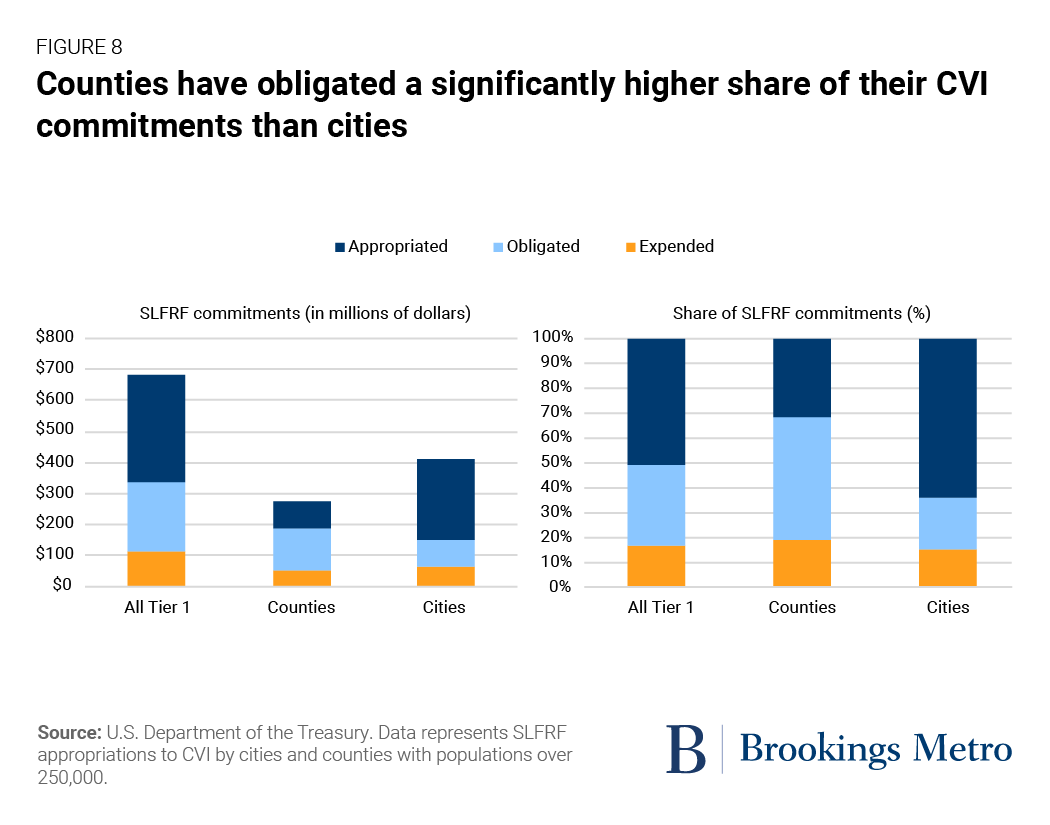

Looking ahead: Appropriations to CVI are important, but obligations matter most for the 2024 deadline

Our analysis found significant variation between the rate at which cities and counties are appropriating and obligating funds to CVI strategies (Figure 8). While Tier 1 cities and counties are spending SLFRF dollars committed to CVI at similar rates, counties have obligated a much larger share of these investments (68% in counties, compared to 36% in cities). This is important because timing matters for obligations; while local governments have until the end of 2026 to spend their SLFRF allocations, they must obligate all funds by December 31, 2024. This means that compared to counties, cities will face much more substantial time pressure to obligate their CVI appropriations by the 2024 deadline.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that across the U.S., most local governments are missing the opportunity to leverage ARPA funds to invest in CVI, and of those investing in CVI, many are missing their time-limited window to embrace root cause approaches at the level of investment needed to scale and sustain impact. It is undeniable that ARPA is enabling some regions, particularly in the Midwest, to stand up root cause CVI investments, but many of these investments are being made in the same select cities and counties rather than being adopted nationwide.

While still early, our analysis indicates several insights that merit additional research:

- More work is needed to scale, support, and sustain CVI as a field. Despite guidance from the Biden administration on how to use ARPA to advance community violence intervention (combined with pressure from constituents to address the pandemic-era spike in gun homicides), only 28% of Tier 1 cities and counties used SLFRF dollars to fund CVI approaches. As a field that has traditionally lacked sufficient public sector funding and is often strapped to pay its workers due to resource constraints, this relative lack of SLFRF investment indicates that more explicit efforts to scale and sustain CVI may be needed, such as dedicated federal programs that explicitly support root cause safety solutions.

- Regional dynamics matter in CVI investment patterns. While some regions, particularly in the Midwest and Northeast, stand out for their adoption of root cause CVI strategies, many have not invested in CVI at all or have relied entirely on carceral approaches. This indicates that regional political dynamics continue to pose an obstacle for local leaders interested in innovative solutions. These regional patterns matter because they mean that, in most large cities and counties (outside of the five discussed in Finding #2), SLFRF dollars intended for root cause solutions are not receiving the level of investment needed to succeed and may end up falling into the trap of “one short-lived pilot project to another.”

- The availability and public awareness of evidence on CVI strategies may impact their adoption. Social cohesion and conflict mediation strategies—including those that employ violence interrupters and credible messengers—saw much wider geographic adoption than other root cause approaches during the SLFRF program’s first two years. This uptake indicates that the broad evidence base underlying these strategies—as well as the public spotlight the Biden administration put on them—may be contributing to greater adoption.

While there is still time for local governments to scale up root cause community safety infrastructure before the SLFRF program’s 2024 obligation deadline, this type of comprehensive strategy-setting will require intentionality and an understanding that the investments made today can lay the groundwork for safe communities in the years to come.

Glossary of terms

ALLOCATIONS are the total funds distributed to state and local governments through the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (SLFRF) program.

AMERICAN RESCUE PLAN ACT (ARPA) is the $1.9 trillion economic stimulus and pandemic recovery legislation signed into law by President Joe Biden on March 11, 2021. This legislation is also referred to as the “American Rescue Plan” or “ARPA.” This brief focuses solely on the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (SLFRF) program, and thus, “ARPA” and “SLFRF” are used interchangeably.

APPROPRIATIONS are dollars distributed to state and local governments through the SLFRF program that have been budgeted or committed to specific initiatives or programs. In this brief, “appropriations” and “commitments” are used interchangeably.

BEHAVIORAL HEALTH INTERVENTIONS are root cause intervention models, including investments in substance use services, mental health services, and non-police crisis response initiatives.

BUILT ENVIRONMENT INTERVENTIONS are root cause intervention models, including crime prevention through environmental design, neighborhood beautification efforts, and other investments in the public realm designed to improve safety, such as streetscape improvements and vacant lot repairs.

CARCERAL CVI APPROACHES are investments in the CVI category that include funding to carceral institutions, such as police, courts, and corrections.

CIVIC CAPACITY-BUILDING INTERVENTIONS are root cause intervention models, including new community grant programs for nonprofits, community safety training for community leaders, funding for standalone community safety agencies (such as offices of neighborhood safety), system-level policy change, new coordinating/intermediary positions (such as community safety liaisons), and community engagement and/or needs assessment funding.

COMMITTMENTS are dollars distributed to state and local governments through the SLFRF program that have been budgeted or committed to specific initiatives or programs. In this brief, “appropriations” and “commitments” are used interchangeably.

COMMUNITY VIOLENCE INTERVENTION is an eligible use category (reporting code 1.11) established by the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s SLFRF Final Rule for recipient reporting on projects pertaining to violence reduction and gun violence mitigation.

CORONAVIRUS STATE AND LOCAL FISCAL RECOVERY FUNDS (SLFRF) is the $350 billion program authorized by the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) that provides economic stimulus and pandemic recovery funding to U.S. states, territories, cities, counties, and tribal governments. This brief focuses solely on the SLFRF program, and thus, “ARPA” and “SLFRF” are used interchangeably.

ECONOMIC ASSISTANCE INTERVENTIONS are root cause intervention models, including investments in youth and adult workforce/job training programs, financial assistance and wraparound services, literacy training, housing and rental assistance, and reentry services.

OBLIGATIONS are dollars distributed to state and local governments through the SLFRF program that have been legally dedicated to specific uses, frequently (but not exclusively) through contractual agreements.

REVENUE LOSS is a provision of the SLFRF Final Rule that allows local governments to classify some or all of their allocations as “revenue replacement.” Local governments may claim up to $10 million as “revenue replacement” as a standard allowance without any requirement to demonstrate a loss of revenue, or more if they are able to demonstrate a loss of revenue attributable to the COVID-19 pandemic.

REVENUE REPLACEMENT is an eligible use classification established in the SLFRF Final Rule. Funds classified as “revenue replacement” through the SLFRF program’s revenue loss provision can be used for any government service permissible under state law and are not subject to many SLFRF programmatic reporting requirements.

SOCIAL COHESION AND CONFLICT MEDIATION INTERVENTIONS are root cause intervention models involving violence interrupters, credible messenger programs, mentoring initiatives, and other pro-social activities designed to improve safety.

TIER 1 LOCAL GOVERNMENTS are metropolitan cities and counties with populations greater than 250,000. These jurisdictions are also referred to as “large local governments” or “large cities and counties.”

TRAUMA AND VICTIMIZATION INTERVENTIONS are root cause intervention models, including programs for domestic violence, human trafficking, child abuse, and gender-based violence survivors; supports for victims and families of gun violence (including hospital-based intervention); and healing-centered/trauma-informed programs.

-

Footnotes

- This brief focuses exclusively on Tier 1 cities and counties (those with populations over 250,000) but recognizes the important role states can play in CVI allocations at the local level.

- SLFRF project and expenditure reporting code 1.11.

- Washington, D.C. has appropriated more than $15.2 million through the SLFRF program to hire new police officers. However, these funds are classified as “revenue replacement” and are not included in this analysis.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).