Education technologies like personalized learning have tremendous potential to help students learn. To maximize the value of personalized learning, the public and private sectors must increase their investments in training, infrastructure, hardware, and curriculum. Unfortunately progress in each of these areas is uneven.

In a recent Chalkboard post, I discussed the potential benefits from broad adoption of personalized learning. A key reason that I remain skeptical about the long-term impact of personalized learning is the lack of bandwidth in the nation’s schools. The available data suggests that school internet speeds continue to rise at a rapid rate, but remain below the levels needed to support broad adoption of personalized learning.

The most recent and comprehensive data on school internet speeds is collected by the nonprofit Education SuperHighway (ESH). They analyze school district applications to the Federal Communication Commission’s E-Rate program. E-rate provides funding to schools and libraries to subsidize the cost of internet access. ESH then contacted schools to verify the connection types and bandwidth for the 2015 funding year.

Many school districts lack high-speed internet

In their 2015 report, ESH finds that schools have made considerable progress. In 2013 the FCC established a minimum bandwidth target of 100 Kbps per student [1]. ESH found that 30 percent of school districts meet that low standard. Over the next two years that figure rose to 77 percent of school districts. Only Wyoming and the single district-state of Hawaii have reached the 2013 goal. Since then the FCC has set the ambitious goal of 1 Mbps per student by 2018. Some schools have already met this lofty standard, but the vast majority have not.

Providing high-speed broadband to the communities that currently lack access will require an ambitious effort. Broad swathes of the country remain unconnected to terrestrial broadband options. There are a variety of technologies that could provide access to these school districts, but companies are reticent to offer services in communities with few customers. Governments can fill in the gap but it would require larger subsidies to Internet Service Providers (ISP).

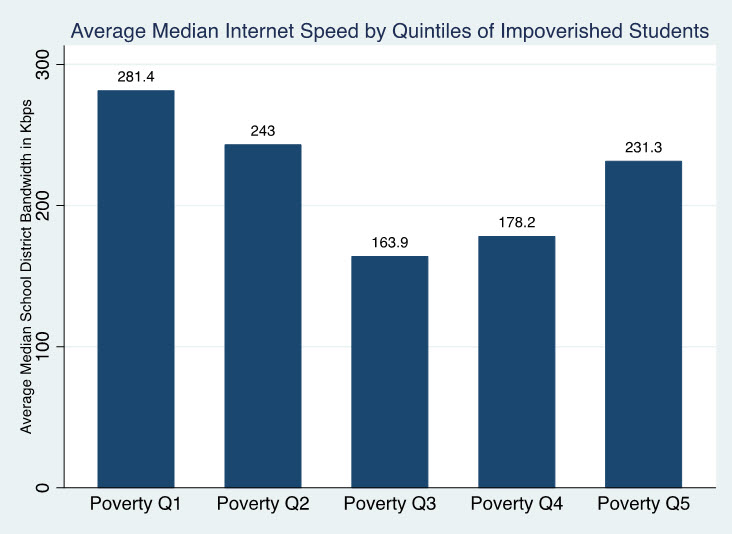

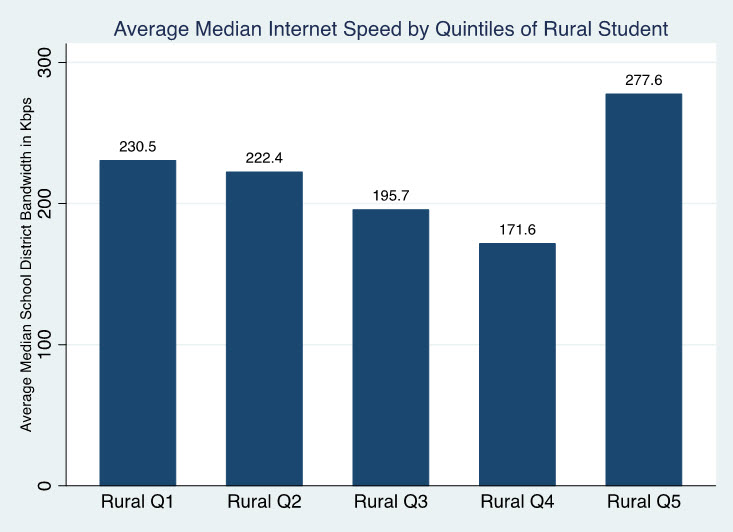

The average median bandwidth for states was 220 Kbps per student. States with few impoverished students (lowest quintile) had a high median bandwidth speed (281 Kbps per student). But, states in the top quintile for the number of students in poverty also had an above average school district median bandwidth of 231 Kbps per student. A similar pattern follows for the number of students living in rural areas. States in the lowest and highest quintile for the number of rural students had higher median bandwidth connections than states in the third and fourth quintile.

Source for both charts: Author’s Calculation from ESH Compare and Connect K-12

Differences within states

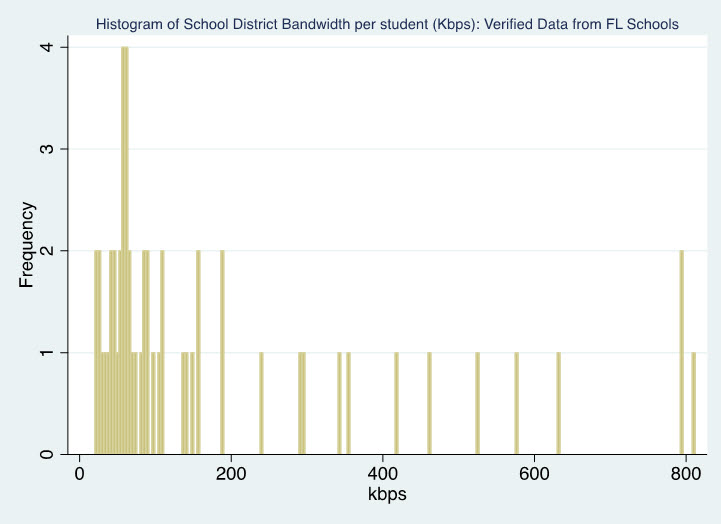

The state-level data on broadband speeds mask considerable variation at the district level. For example, in Florida, the median school district broadband speed is 82 Kbps per student and 40 percent of school districts have an average speed of at least 100 Kbps. Escambia County in the panhandle has an average speed of 20 Kbps per student while Glades County in south-central Florida averages 812 Kbps per student.

Source: Author’s Calculation from ESH Compare and Connect K-12

One possible explanation is that states with greater numbers of impoverished and rural students have slower internet connections. Impoverished and rural communities do not have the customer bases to attract infrastructure investments from ISPs. However, the number of rural students and the number of students in poverty have weak relationships with the median state bandwidth. The Florida data suggest that bandwidth speeds vary more within rather than across states.

Why does this matter?

100 Kbps per student is not fast enough to support personalized learning. State Education Technology Directors Association’s (SETDA) recommends downlink bandwidth speeds of 100 Kbps per student as a minimum. For example, SETDA recommends 250 Kbps per student for online learning. For a bandwidth-intensive platform like Khan Academy they recommend 1.5 Mbps per device. Many districts are far from these targets.

Without a clearer view of school bandwidth and peak internet usage it’s not possible to understand the nature of the problem. This presents an additional difficulty to policymakers who seek to address this issue. Is the current 2018 FCC standard of 1 Mbps per student fast enough for every student in the country to take an online standardized exam? There is no research yet that allows for a precise answer to this important question. The last national study of school internet speeds occurred in 2005. The federal government could address this problem by administering a survey about school internet access. This would provide a more detailed picture about peak usage rates and current speeds.

If personalized learning and other internet-enabled educational tools are to realize their potential then substantial infrastructure investments in wireless broadband, fiber, and other technologies are needed. Ensuring that every school has the necessary bandwidth is a difficult task because it would require a massive investment from public and private sources. Policy analysts and advocates should take into account this challenge when predicting the adoption and impact of personalized learning.

Note: [1] ESH defines Internet Access bandwidth per student as “For Internet access, total bandwidth per district is calculated as the sum of the capacity of all Internet Access connections divided by the total number of enrolled students in the district as reported in NCES data.”

The FCC’s 100 Kbps per student standard is based on SETDA’s recommendation.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).