Americans used to be a nomadic bunch, uprooting themselves for better jobs, better housing, and better lives, but new Census data again confirms a trend first observed at the nadir of the recession: We’re becoming a nation of homebodies, and not by choice.

Census Bureau data released this week reveal that the rate of Americans moving reached another new postwar low in 2011. The mutually reinforcing constraints of a stalled housing market on the ability to move for employment bodes poorly for economic recovery, though the slowdown may also provide windfall population gains for some places that need them.

The new statistics indicate that just 11.6 percent of U.S. residents moved between 2010 and 2011, down from 12.5 percent the previous year, and the lowest rate since 1948. To put this in proper perspective: the 35.1 million people who changed residence last year is the lowest number since 1960, when the nation’s population was about 40 percent smaller.

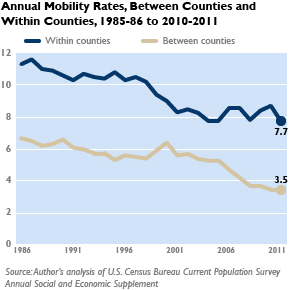

The new low point represents a confluence of two different troubling patterns. The first, reported earlier, is the sharp drop-off in “longer distance” migration rates (both between counties and between states) after 2007. That dip reflects the impact of the recession and the housing market crash. The historically low share of Americans moving across county lines remained at 3.5 percent for the second straight year.

The second pattern is a new historic low point for local within-county residential movement. The drop in local mobility follows a gradual long-term decline associated with the aging of the population and higher homeownership levels in recent decades. Yet, the new rate of 7.7 percent is lower than the previous low in 2007-08, and well below rates in the 9 to 10 percent range that prevailed during the 1990s. The lackluster housing market and more stringent credit policies help explain the new low. Indeed, the small uptick in this rate during the two previous years can be attributed, in part, to the reshuffling of households resulting from foreclosures and “doubling up.”

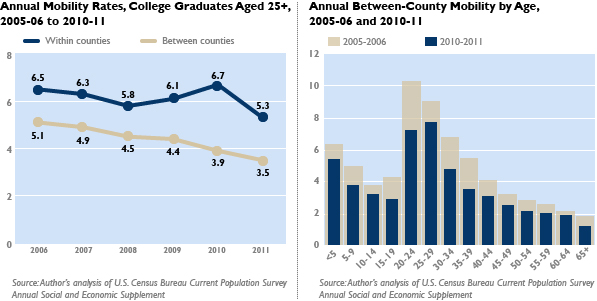

Additionally, the new numbers show historically low local and long distance migration rates for two key groups. Adult college graduates, the lifeblood of the national labor market, are not finding jobs in new places, and appear to be staying in their homes. Meanwhile, young adults in their early 20s—newly graduated from college or starting out in life—are moving much less, especially between counties, than just five years ago.

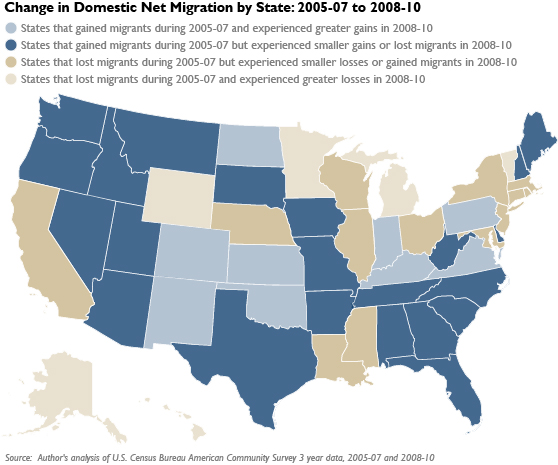

The newly flat-footed American population continues to avoid former migrant magnets in the Sun Belt. In metropolitan Phoenix and Las Vegas, the housing bubble coincided with unusually high mid-decade population gains from migration. As these flows dissipated, prior “feeder areas” in California and other parts of the West enjoyed a population windfall.

Similar dynamics fueled, then cooled, movement to southeastern magnets like Orlando and Atlanta from metropolitan New York and other parts of the Northeast and the Midwest.

Yet the slowdown has also affected broader parts of the nation. Among 31 states that gained migrants during the pre-recession 2005-07 period, 22 either gained fewer migrants, or lost migrants in the 2008-10 period. Among the 20 states (including the District of Columbia) that lost migrants in the former period, 13 either lost fewer or actually gained migrants in the latter period, including California, New York, and Massachusetts (see Table).

A foreboding trend for national economic recovery thus presents an opportunity for former “exporter” states and metropolitan areas like Los Angeles and New York to convince their newfound, if reluctant, residents to remain, even after migration opportunities to seemingly more attractive locales again open up. Indeed, this audition period could be a long one if the current migration slowdown persists.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Americans Still Stuck at Home

November 17, 2011