Leaving the Paris Agreement is one in a string of absurd foreign policy decisions that have quickly undermined the country’s credibility as a partner in international cooperation, writes David Victor—credibility that is essential not just to protecting the environment but also managing immigration, sharing intelligence, slowing the spread of nuclear weapons, avoiding pandemics, and a host of other things that Americans care about. This piece originally appeared on Yale Environment 360.

Finally, the shoe has dropped. The United States will leave the Paris agreement, Donald Trump announced on Thursday. Trump’s America, he says, is putting itself first.

For the master negotiator, as Trump fancies himself, this decision is one of the biggest negotiating blunders of his presidency so far. He has confused self-interest, which almost every nation puts first, with strategy. And he seems to understand almost nothing about the climate change problem nor the Paris framework he loathes.

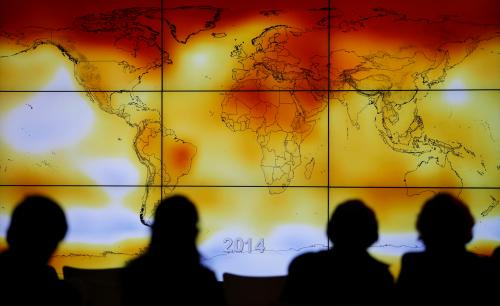

Making cost-effective cuts in the emissions that cause climate change is firmly in America’s self-interest. Our beaches will erode from higher sea levels, our storms will become more severe, and heat waves will be more intense. Our natural ecosystems are fragile, just as in many other countries, and they will suffer.

Since the U.S. only accounts for about 15 percent of global emissions, it can’t do much about the problem unless other nations come along as well. Paris, which American diplomats played a central role designing, would provide just that. Today, the Paris agreement doesn’t require that any country do much beyond what it would do otherwise. Paris is about the long game—laying a foundation for deeper cooperation as countries learn more about what they are willing and able to do.

Staying in Paris would have been easy.

A host of studies has shown that the U.S., no matter who sits in the Oval Office, was not on track to meet the Obama-era pledge made under the Paris agreement to cut emissions 26 percent to 28 percent below 2005 levels (see studies here and especially here). To be sure, since Trump took office, his policies have made that even harder, but not by much. Yet rather than deal with this reality, Trump praised a study showing that the economy would be plunged into darkness if forced to meet Obama’s pledge—a scenario that few, today, take seriously.

Pointing to a fake scenario and ignoring the easy option of adjusting the pledge made by the U.S., Trump saw no other choices but exit. That choice runs exactly counter to America’s interests—to what a real America First president would demand—and led the president to select the worst option for changing the U.S. relationship to Paris.

The really odd thing about all this isn’t just the wrong-headed analysis of America’s interests on climate change. It is that for a president obsessed about getting a fair deal on the global stage, his foreign policy choices will make fairness even harder to obtain. Leaving Paris is one in a string of absurd foreign policy decisions that have quickly undermined the country’s credibility as a partner in international cooperation—credibility that is essential not just to protecting the environment but also managing immigration, sharing intelligence, slowing the spread of nuclear weapons, avoiding pandemics, and a host of other things that Americans care about.

Leaving Paris is one in a string of absurd foreign policy decisions that have quickly undermined the country’s credibility as a partner in international cooperation.

The rest of the world won’t sit idly as the country that traditionally has been the main supplier of global public goods creates a vacuum in leadership.

Many countries are now jockeying to fill the vacuum that is being left by the U.S. Most interesting to watch in that process is China. Across the board, where America is leaving China is saying it will do the opposite, whether it is Chinese President Xi Jinping’s speech in favor of globalization in Davos or China’s steadfast support for the Paris process. So far, this vacuum filling is more symbolic than substantive; it has not required China or other countries to do much that is different from what they would do otherwise. But rhetoric will give way to reality and the harm to America’s credibility and standing in the world will be palpable.

A place to watch is the delivery of the $100 billion pledge reaffirmed in Paris. This money, promised by the wealthier nations to help the poorer, is a key part of the political glue that holds the Paris process together. The developing countries—especially the least developed countries—were expecting new funds to help them engage with the process and, especially, to help them manage the costs of adapting to a rapidly changing climate. Some of these countries—such as the low-lying island nations—are extremely vulnerable to climate change and aren’t, themselves, responsible for creating these problems. As they lose faith that these funds will flow, they will become a lot less cooperative in international diplomacy, making it harder to reach deals that require global consensus.

Over the last few years, both the U.S. and China—along with many other countries—have made concrete pledges for a first tranche of funding. All told, they have committed more than $10 billion to be spent over the coming three years starting around 2015—funds are already flowing—with more money after that. (The $100 billion figure includes both these official funding flows from governments as well as capital mobilized from the private sector. The exact balance between public and private funding has never been clear by design, but most analysts expect that most of the money will eventually come from the private sector.)

China, if it continues to play its cards well, could become a major source of innovation and good will on climate change.

While both the U.S. and China made big pledges, the two countries have followed diametrically opposite paths in delivery. Under Obama, the U.S. pledged $3 billion and actually delivered $500 million of that total. One of Trump’s first actions on climate change was to cancel the remaining amount. And in his announcement on Thursday, he puffed that the U.S. was exposed to “billions and billions and billions of dollars” of commitments, including to the fund, and few others have paid much or anything. The real story is quite different. China has actually made a bigger pledge—although it is running its money through its own mechanisms, as the Paris agreement allows, rather than through the official Green Climate Fund.

China, if it continues to play its cards well, could become a major source of innovation and good will on climate change.

What will all this mean for Paris itself?

Some foreign policy analysts suggest that other countries will also head for the exit. I suspect the opposite will happen—in part because Paris hasn’t required that they do much beyond what they were planning anyway and in part because staying engaged when Trump leaves has become more popular than ever in some countries.

The basic idea built into the Paris agreement still makes sense. Countries make pledges for the efforts they will undertake and then conduct periodic reviews to check to see what is working and not. Over time, this process of pledge and review would make deeper cooperation easier. Charles Sabel, a law professor at Columbia University, and I have been calling this experimentalist governance of climate change. Countries, firms, and NGOs are committed to do something about global warming, but nobody really knows what will work and at what scale—policy experiments and learning are essential.

America’s exit isn’t good news for Paris, despite what some analysts have argued. The U.S. almost always plays a key role in building effective international institutions. Without America, leadership is diffused and harder to muster. The list of things left undone in Paris remains very long, and leadership is essential to turning the Paris framework into something truly effective. Without the U.S., the Paris process has lost an important leader in making the Paris pledge and review vision effective, but the idea still makes sense. And the countries left behind will still keep pushing forward.

The good news in this is that Trump’s exit, while inflicting harm, is not permanent. The amount of damage that Trump’s administration can do to U.S. national policy on climate change is large, but it is constrained by rigidities in the political system and in the long-term nature of energy investments. The Clean Power Plan, for example, might be rolled back—but nearly all firms are already implementing lower-carbon investment strategies that are consistent with the plan. And the very toxicity of Trump’s policies to many in the country has made it very popular for other power centers in the U.S. to do the opposite. On many fronts—climate as well as immigration and public sector funding for research—California, for example, is doubling down. Governor Jerry Brown heads to China today for talks that will focus on climate change perhaps more than any other topic. While Washington burns, the states are alive and well and have become much more positive conveyors of the country’s foreign policy messages.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

America heads to the exit: What Trump got wrong about Paris

June 6, 2017