Across partisan, ideological, and racial lines, Americans are rethinking the country’s criminal justice system. The Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act (S. 2123) and the Sentencing Reform Act of 2015 (H.R. 3713) have passed out of the Senate and House Judiciary Committees respectively and earned support from a bipartisan group of elected officials, the White House, and advocacy organizations including the American Civil Liberties Union and Koch Industries.

Criminal justice reform must strike a balance between reducing the federal prison population and safeguarding the public from crime. The Senate bill, as well as its House companion, would reduce mandatory minimum sentence length for certain offenders and expand recidivism reduction programming. According to Senator Chuck Grassley (R-IA), the Chairman of the Judiciary Committee, the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act addresses “legitimate over-incarceration concerns while targeting violent criminals and masterminds in the drug trade.” Recently, however, Senator Tom Cotton (R-AR) has led a cadre of conservatives in objecting to criminal justice reform. Speaking on the floor of the Senate, Cotton declared the legislation a “massive social experiment in criminal leniency…[that] threatens to undo the historic drops in crime we have seen over the past 25 years.”

To understand the state of the nation’s criminal justice system and evaluate the challenges and opportunities of the proposed reform, let us first consider the magnitude of the U.S. incarcerated population.

The prison population buildup

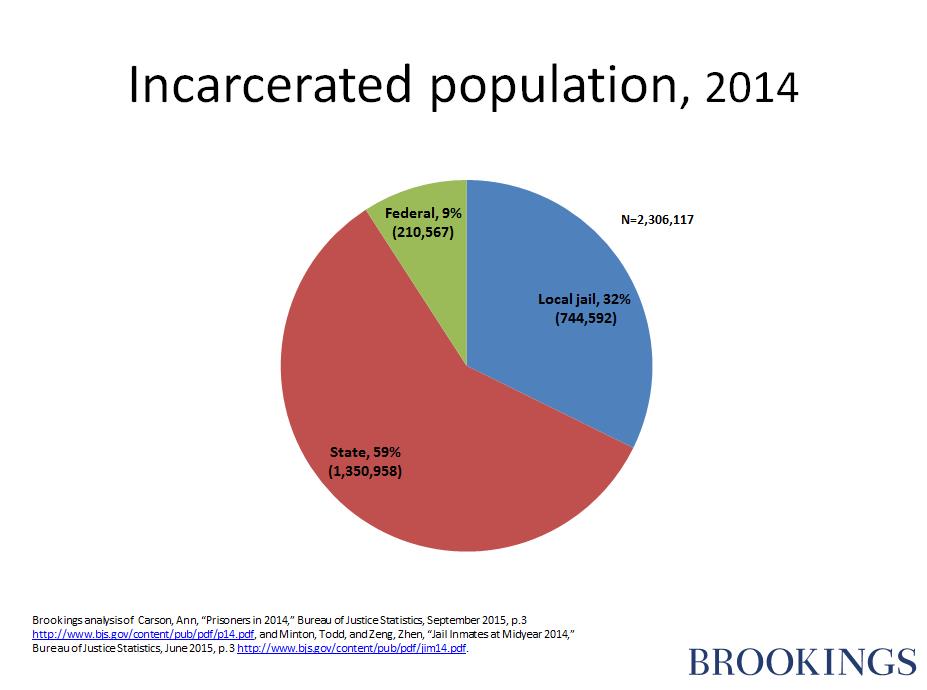

The combined local, state, and federal prison populations in the United States totaled 2,306,117 in 2014, the most recent year for which data is available. Although the states incarcerate the greatest number of people collectively, the federal prison system is the nation’s single largest jailer [Figure 1].

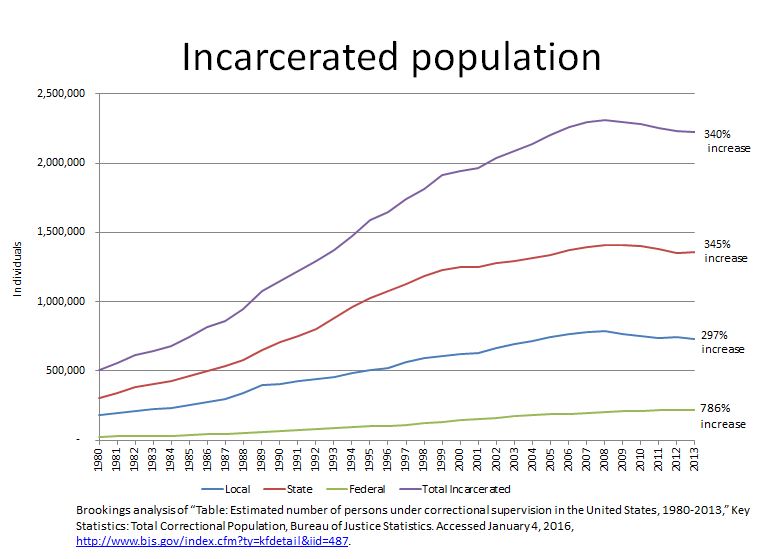

Between 1980 and 2013, the most recent year for which comprehensive time-series data is available, the combined federal, state, and local prison populations ballooned, increasing 340% from 503,600 to 2,200,300 individuals. In this time period, the federal population expanded most rapidly, with an increase of 786% from 24,363 to 215,866 individuals [Figure 2].

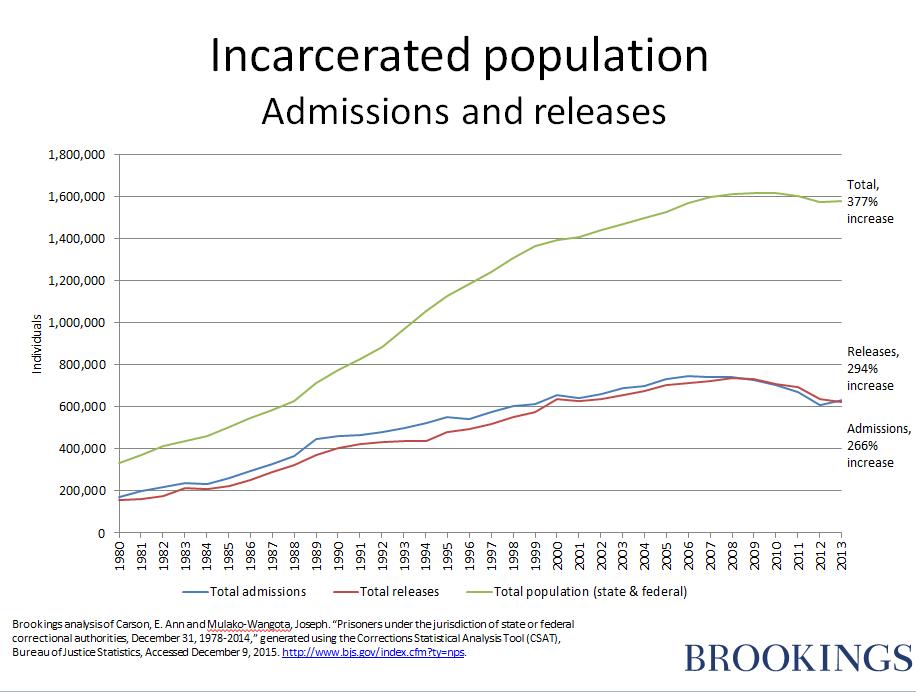

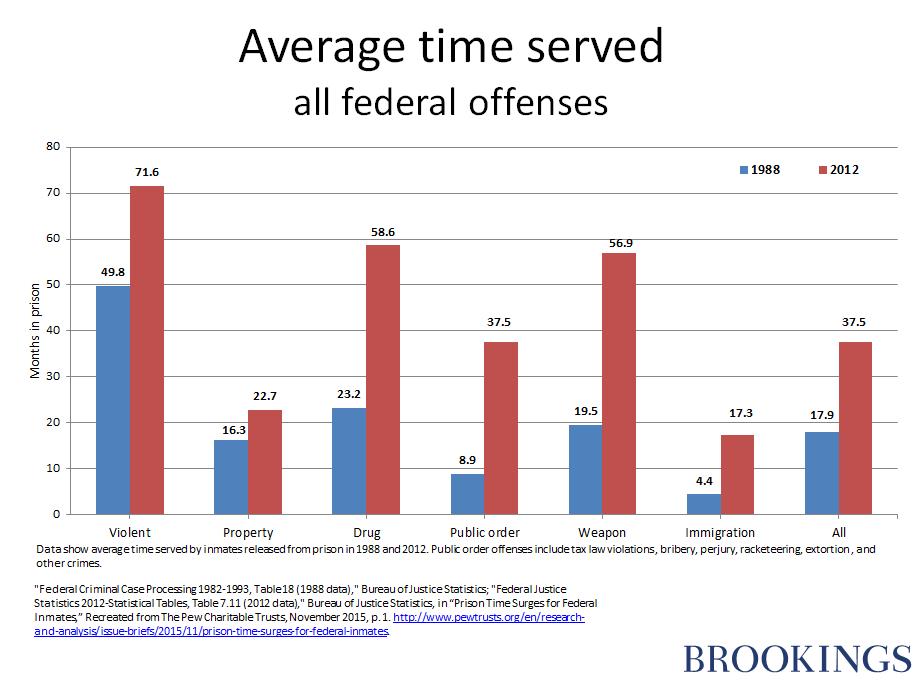

The increased prison population is the cumulative result of decades in which the number of individuals admitted to prison outpaced the number of individuals released [Figure 3]. The steep increase in the rate of admission is attributed to a number of factors including prosecution, investigation, and sentencing rates. The sharp decrease in the release rate is the product of policy choices to increase sentence length and decrease parole. A striking report by the Pew Charitable Trusts shows that the average length of time served by federal inmates more than doubled from 1988 to 2012 [Figure 4].

The population of individuals incarcerated in the United States is unique among western, liberal democracies, and this has deleterious social and fiscal consequences for taxpayers and even more, for those imprisoned. As the bipartisan, blue-ribbon Charles Colson Task Force on Federal Corrections concluded after months of rigorous, evidence-based policy examination, the status quo of incarceration in the United States is unsustainable. It is against this backdrop of necessity that we evaluate reform measures in the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act.

Low-level drug offenders

Sections 101, 102, and 103 of the bill pertain to federal drug offenders. Drug offenders comprise an estimated 50% of the incarcerated population—the single largest category of federal felons. This means that reducing sentence length for certain types of drug offenders has the potential to significantly reduce the prison population.

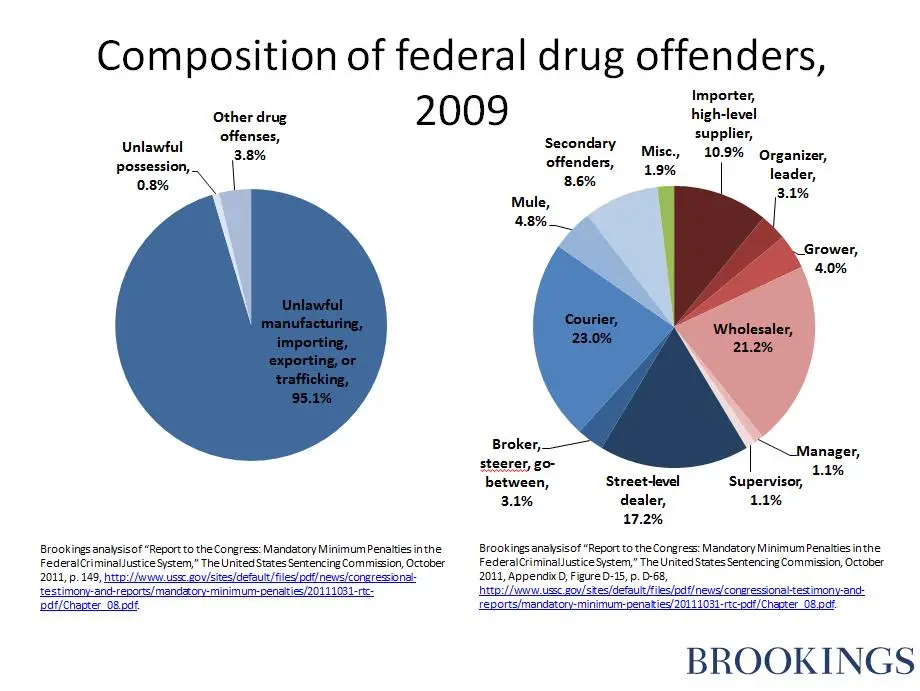

Senator Cotton has expressed concern that these reforms would “reduce sentences not for those [prisoners] convicted of simple possession, but for major drug traffickers.” As we argue in another post, the Senator’s claims are subject to interpretation. The statutory definition of “drug trafficker” pertains to an estimated 95.4% of individuals incarcerated at the federal level [Figure 5], but the term is broad in that it encapsulates a number of low-level offenders, including street-level dealers, brokers, couriers, and mules [Figure 5].

To address mass incarceration in a way that targets low-level offenders, lawmakers must distinguish between the offenders who played an organizational role in the drug trade versus those who played a relatively low-level role in drug distribution. Critically, the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act makes this distinction, specifying that sentence reduction would not apply to drug offenders who served as importers, exporters, high-level distributors or suppliers, wholesalers, or manufacturers.

Firearms

Sections 104 and 105 of the legislation would reduce sentence length for some firearm offenders. Roughly 16% of federal prisoners were weapons offenders, the second largest category after drug offenders. This is a substantial part of the prison population, so sentencing reform for key categories of offenders could make a meaningful impact on the size of the federal prison population. When it comes to squaring the impetus to reduce incarceration with concern for public safety, however, the politics become especially tricky.

For instance, a provision of Section 105 would reduce enhanced mandatory minimums for “armed career criminals” from 15 to 10 years. This would reform the Armed Career Criminal Act (ACCA), 18 U.S.C. 924 (e), which requires imposition of a minimum 15-year term of imprisonment for recidivists convicted of unlawful possession of a firearm, as defined by 18 U.S.C. 922 (g), if they have three prior state or federal convictions for violent felonies or serious drug offenses. In this instance, a “serious drug offense” is one punishable by ten years imprisonment; a “violent felony” is one that (1) has an element of threat, attempt, or use of physical force against another or (2) is burglary, arson, or extortion, involves the use of explosives, or otherwise involved conduct that presents a serious potential risk of physical injury to another.

In this case, there is little question that the offenders who would stand to benefit from sentencing reform committed several serious crimes. The proposed legislation, however, would not exonerate these individuals—far from it, in fact. The legislation maintains ten years of compulsory sentencing and permits judges a modicum of discretion to review the facts of an individual’s case and recommend additional years behind bars if they deem it appropriate.

If lawmakers are serious about reducing the federal prison population, reforms that target low-level drug offenders and certain weapons offenders will have the greatest impact. As lawmakers assess criminal justice reform in the Senate and in the House, they must recognize the gravity of the over-incarceration epidemic and look to the facts as they consider the offenders who would be affected by reform.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Addressing mass incarceration with evidence-based reform

April 8, 2016