Editorial Note: This is a modified post based on the

full version

posted on the Health Affairs blog on February 14, 2014.

It seems that bipartisanship has reappeared in healthcare reform, as the three Congressional committees with Medicare jurisdiction recently agreed on a framework to repeal the sustainable growth rate (SGR) formula that is used to pay physicians and other healthcare providers. If passed into law, the SGR Repeal and Medicare Provider Payment Modernization Act of 2014 will signify a major step forward in transitioning Medicare’s payment system away from a fee-for-service (FFS) model that incentivizes volume and number of procedures, toward a value-based model that rewards improvements in quality of care and population health.

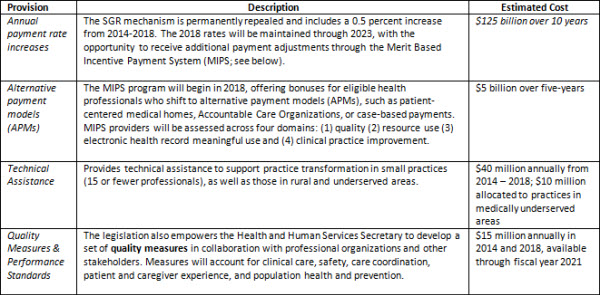

However, the biggest obstacle ahead is deciding how Congress will pay for the proposed “doc fix.” The Congressional Budget Office estimates suggest the physician payment reform bill will likely cost around $130-$170 billion, most of which would be needed to offset the scheduled payment cuts under the existing SGR formula. Although the SGR system was initially implemented to contain Medicare cost growth, relying on across-the-board payment cuts has not worked well in practice. Congress has enacted short-term patches to delay cuts each year since 2002, and as a result, the gap between actual Medicare spending and the SGR spending target has widened so much that physician payments will be reduced by 24% if Congress fails to act by April 1st. Below we provide a brief outline of key provisions in the legislation and their estimated costs.

Key Provisions and Costs: SGR Repeal and Medicare Provider Payment Modernization Act of 2014 (HR4015)[1]

Paying for a New Medicare System

The Congressional committees have floated a list of potential sources[2] of savings to pay for these reforms, but there is a bigger opportunity here than just stabilizing physician payments. Instead, lawmakers, advocates, and health professionals should consider this rare opportunity to build a modern Medicare payment system that rewards better delivery of care and patient experience, improves population health, and reduces costs and system inefficiencies. Our proposed reforms to offset these costs reinforce the goal of the physician payment reforms—better care at a lower cost. If implemented together with the physician payment reforms, the whole package could have a more meaningful effect on beneficiary care and Medicare cost growth than the physician payment reforms alone. Below is a set of recommendations to help subsidize the costs of an SGR repeal and transition to value-based Medicare.

Pay for post-acute care based on patient’s health status and needs, not where care is received.

Estimated savings: $45 billion over 10 years[3]

Medicare often pays varying amounts for care once a patient leaves the hospital, based not on their health needs but on whether they receive care in an inpatient rehabilitation facility, a nursing home or in their own home. Substantial evidence suggests that this approach is inefficient, and that many beneficiaries could receive appropriate care in less intensive and more convenient settings.[4]

Enhance incentives for hospitals that improve post-acute care and lower readmissions.

Estimated savings: $10-$15 billion[5]

Hospital readmissions are costly and can sometimes be avoided when patients receive proper, well-coordinated follow-up care. While the readmissions penalties included in the Affordable Care Act have led to a lower readmissions rate than in the past, the incentives for hospitals to pay attention to the care patients receive once they leave the hospital could be strengthened. In exchange for higher base rates, hospitals could assume greater responsibility for coordinating post-acute care and share in the savings that result from lower readmissions and working more efficiently with post-acute care providers. Hospitals could also bear more of the costs when they fail to achieve lower readmission.

Pay for outpatient care based on services provided, not the type of facility.

Estimated savings: $10-$15 billion[6]

Similar to post-acute care, Medicare pays different rates for outpatient services based on facility type. In particular, Medicare pays a substantially higher amount for certain services provided in a hospital outpatient department, when the same services could be provided safely and effectively in a doctor’s office or other primary care setting. Without reform, higher payment for these services when a physician practice is part of a hospital conflicts directly with the goal of supporting a value-based system.

Use competitive bidding to set payments and improve quality, starting with lab tests.

Estimated savings: $8 billion over 10 years[7]

Medicare’s method for reimbursing many services besides physician care is based on detailed fee schedules that are difficult to update as costs of services or products go down, and as new ones are introduced. For example, technological improvements for laboratory tests have brought down the costs of both individual tests and batteries of tests, indicating that Medicare was overpaying by about $900 million a year.[8] One approach is to use competitive bidding to determine payments for basic lab tests and expand this approach to other services over time. Medicare has begun paying for some “durable medical equipment” products through competitive bidding, with substantial savings.

Reform Medicare benefits through a phased-in approach.

Medicare’s existing benefit structure also prevents beneficiaries from saving money when they choose high-quality, low-cost care, nor do they provide the best protection against high out-of-pocket expenses. Several organizations have outlined options to reform Medicare benefits, including Brookings, the Bipartisan Policy Center (BPC), and MedPAC.[9] We recommend gradually phasing in a similar set of benefit reforms.

Reform Medicare supplemental insurance (Medigap) to eliminate first-dollar coverage.

Estimated savings: $50 billion or more over 10 years (if implemented immediately)[10]

Supplemental Medigap coverage that eliminates all Medicare cost sharing (say, below 10% up to an out-of-pocket limit) could be prohibited, or alternatively, beneficiaries who choose such coverage would pay a fee that reflects the impact of their “first-dollar” coverage on overall Medicare costs.

Create a single deductible and an out-of-pocket limit for hospital and ambulatory services (Part A and Part B) and reform Medicare copayments.

Estimated savings: $50 billion (if implemented immediately)[11]

Like all other modern insurance, Medicare should have a single deductible for hospital and physician services and a limit on individuals’ total out of pocket expenses. This reform would also implement reasonable copayments where they don’t exist and reduce those that are excessive.

Implement these Medigap and benefit reforms together.

$110 billion in total savings over 10 years[12]

These reforms would have reinforcing effects on each other. For example, an out-of-pocket limit and copayment reforms in Medicare’s benefit package would enable the reforms in Medigap to have a greater impact, reducing Medicare costs and Medigap premiums further while still giving beneficiaries better protection against high costs.

Phase in the benefit reforms.

$20 to $40 billion over ten years (if phased in as recommended)[13]

To limit disruptions, the benefit reforms could be phased in over time, such as introducing a modest premium surcharge for beneficiaries with the most generous Medigap plans, gradually adjust deductibles and copayments, or apply them to all new Medicare beneficiaries starting in five years.

Reward beneficiaries for efficient prescription drug use.

$30 billion over ten years[14]

Under the current Medicare program for prescription drug coverage, low-income beneficiaries receive additional subsidies that reduce the amount they have to pay for their prescriptions, especially for brand-name drugs, and means they save very little when they choose available lower-cost but equally effective drugs. Introducing modest increases in copayments for brand-name drugs for those receiving low-income subsidies would help encourage more efficient prescription drug use without reducing the quality of care.

Raise the Medicare premium for higher-income individuals.

$60 billion over ten years[15]

Many bipartisan Medicare reform proposals have included additional means testing as a way to reduce Medicare spending. While this reform might be viewed as primarily shifting Medicare costs from taxpayers to higher-income beneficiaries, it too could be phased in over time and eventually paired with reforms that enable beneficiaries to lower their payments when they use less-costly, high-quality care.

Time for Reform

The unprecedented progress in Congress toward reforming Medicare’s physician payment system holds out real hope that Medicare can become a support rather than a recurring obstacle to physician leadership in improving American health care. The biggest remaining obstacle is how to pay for it. Through the reinforcing Medicare reforms that we have described here, truly meaningful, bipartisan Medicare reform may be closer than ever.

[1]

http://beta.congress.gov/113/bills/hr4015/BILLS-113hr4015ih.pdf

[2]

http://www.cq.com/pdf/govdoc-4415898

[3]

http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/44906-HealthOptions.pdf

[4]

(

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission 2011

,

Gage et al., 2012

,

Institute of Medicine 2013

).

[5]

CBO 2013

[6]

(

MEDPAC 2013

).

[7]

http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/44906-HealthOptions.pdf

[8]

https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-07-11-00010.pdf

[9]

Proposals from

https://www.brookings.edu/research/reports/2013/04/person-centered-health-care-reform

;

http://bipartisanpolicy.org/library/report/health-care-cost-containment

;

http://medpac.gov/chapters/Jun12_Ch01.pdf;http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/44906-HealthOptions.pdf

[10]

http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/44906-HealthOptions.pdf

[11]

http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/44906-HealthOptions.pdf

[12]

http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/44906-HealthOptions.pdf

[13]

http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/44906-HealthOptions.pdf

[14]

http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/44906-HealthOptions.pdf

[15]

http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/44906-HealthOptions.pdf

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

A Temp to Perm “Doc Fix:” Paying for the SGR Repeal and Creating Value-Based Medicare

February 19, 2014