Vice President Biden’s announcement that the State Department and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) will establish a refugee resettlement program to enable minors to seek refugee and parole status in the United States is most welcome. The new program was announced at a summit meeting of three Central American presidents on November 14. It forms part of U.S. efforts to address the crisis of children, together with young mothers, crossing the border in the thousands at the Rio Grande valley to reunite with family members in the United States. The program begins this December.[1]

The U.S. government could have relied upon the declining number of unaccompanied minors arriving from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras to avoid any obligation to address the underlying problems. Instead, following Biden’s remarks, the State Department announced straightforward procedures that offer procedural and safe passage into the United States either as a refugee or with parole status. Instead of risking their lives through a treacherous journey to reach the U.S. southern border, unmarried minors under 21-years-old can now be processed in their own countries.

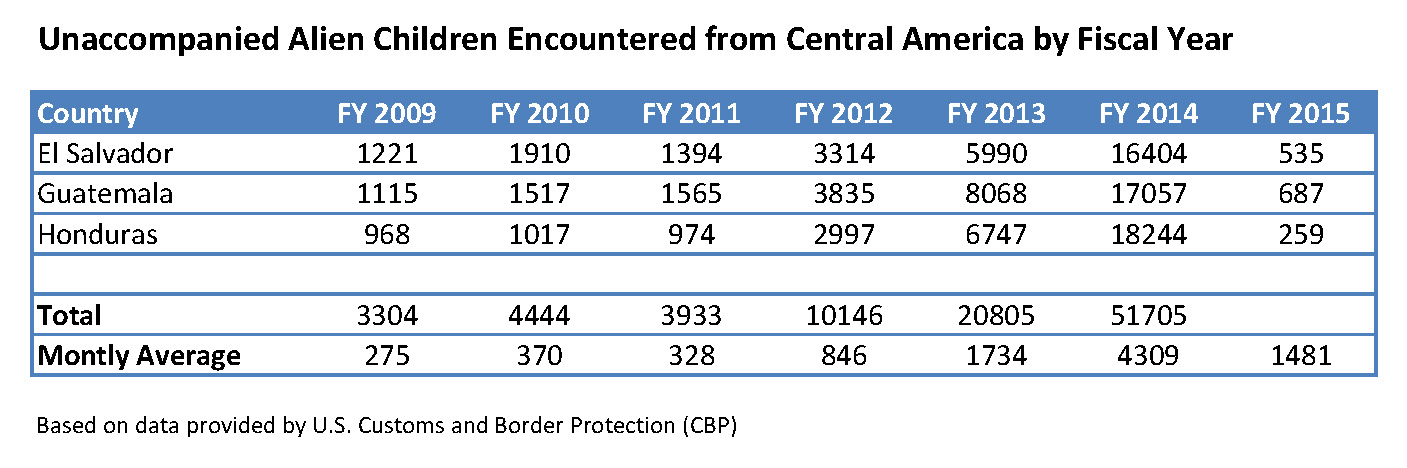

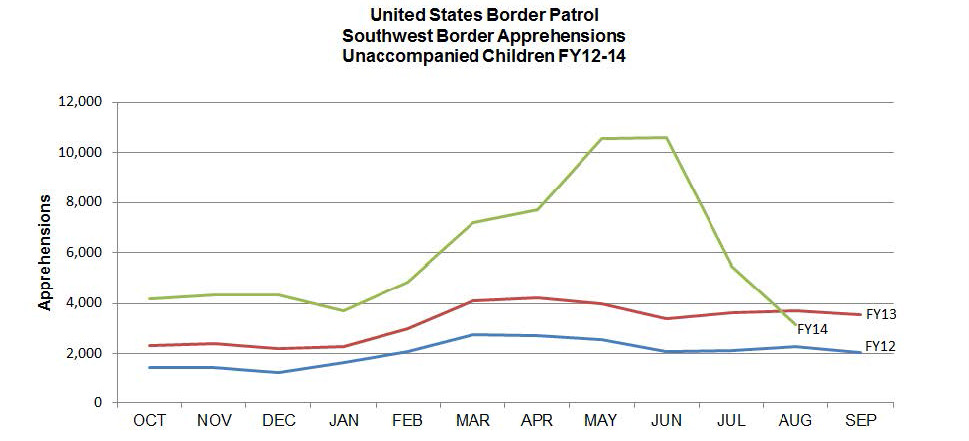

From its high peak of 16,404 unaccompanied minors (0-17-years-old) from El Salvador, 17,057 from Guatemala and 18,244 from Honduras in FY 2014, which ended on September 30, the number of apprehensions at the U.S. border has fallen significantly.

In October 2014, 1,551 unaccompanied minors were apprehended at the Rio Grande Sector compared to 2,652 in October 2013, a 42 percent reduction year on year. However, in the same geographic sector the number of family unit apprehensions increased by 6 percent over the same period.[2] The numbers indicate that a significantly reduced number of unaccompanied children are reaching the southwest border, but mothers and their young children continue to move northward.

Most arrive in search of a parent or close family member. According to a survey carried out by the UN High Commission for Refugees, 48 percent claim that violence in their community forces them to flee. A further 21 percent of the children surveyed claimed abuse and violence from a caretaker in their home.[3] Others seek better economic opportunities, and many claim a combination of all three factors. The State Department recognized that the violence from criminal gangs in the three sending countries, together with the presence of a parent in the United States, provided adequate basis for determining whether the minor was eligible for refugee status, and failing that parole status.

Refugee status

A parent who is legally in the United States can initiate the petition for the minor child or children as refugees with the help of a designated resettlement agency. (A broad range of these agencies are already registered with the State Department’s Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration to help resettle refugees in the United States) A more limited number of designated agencies will be announced to work with Central American petitioners by the end of November. With the help of the agency, the parent legally in the United States will complete a State Department form DS-7699. He or she can also petition for the other parent of the child so long as they are currently married to each other. As part of the petition process, the designated agency will help the U.S. parent submit to DNA testing to confirm biological relationship with the minor child.

In the three Central American countries, the UN’s International Organization for Migration will manage the process by contacting each child and inviting them to a pre-screening interview. The published purpose is to prepare the child for a refugee interview with a DHS official, but we must assume that it is also intended to weed out minors who fail to meet the basic requirements.

With DNA establishing a parental relationship, the child proceeds to an interview with a DHS official in their home country. This is the critical test because DHS will establish whether the child has grounds for refugee status based upon “a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.” The most credible fear for these children is “membership of a particular social group” such that gang members seek to recruit, prostitute or harm them if they refuse to join, or align under pressure with the opposing illicit gang.

Parole status

Should the child not qualify for refugee status, he or she can apply for parole based on a DHS finding that the “individual is at risk of harm, clears all background vetting, there is no serious derogatory information and someone has committed to financially support the individual while in the United States.”[4]

These conditions are not onerous and are intended to protect children from violence, abuse and neglect. Parole does not give the child permanent immigration status or a path to the same. Nor are parolees eligible for medical and other benefits beyond schooling and the right to work. However, the parolee can remain in the United States for two years and may extend that period thereafter.

For those children with legal counsel, a legitimate fear of sexual harassment, bodily harm from gangs or intra-family feuds can often be established, but for those children without counsel and over anxious in the interview with a U.S. official, the grant of parole status is the more likely outcome. We should therefore expect more children to qualify as parolees – entering on a temporary basis rather than permanent refugees.

Ceiling to the number of refugees

Currently 4,000 refugees may enter the U.S. from Latin America and the Caribbean in the fiscal year 2014 to 2015. Given the 61,705 unaccompanied minors detained by Customs and Border Patrol in FY 2014, the current quota will not be sufficient to meet the needs of those who qualify as refugees. Therefore, we should support lifting the current ceiling to accommodate the anticipated larger number of petitioners for refugee status from three northern Central American nations. There is no limit on the number of parolees that may enter the United States in any one year.

The speed with which both State and DHS reached agreement on processing petitioners for refugee and parole status in their respective countries indicates an admirable capacity to adapt. DHS Secretary, Jeh Johnson’s seven visits to the southwest border this year and his interaction with the children have encouraged him to act judiciously and relatively fast. He reflects American compassion toward these children, and often their mothers, who risk so much to join a parent in the United States. The program recognizes that there is a war in Central America and the respective states are incapable of protecting their young citizens from gangs and organized crime. This program responds to Emma Lazarus’ poem engraved in the bronze plaque at the pedestal of the Statute of Liberty:

Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

[1] U.S. Department of State. “Western Hemisphere: In-Country Refugee/Parole Program for Minors in El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras with Parents lawfully President in the United States.” Last modified November 14, 2014. http://www.state.gov/j/prm/releases/factsheets/2014/234067.htm.

[2] U.S. Customs and Border Protection. “Southwest Border Unaccompanied Alien Children.” Accessed November 20, 2014. http://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/southwest-border-unaccompanied-children.

[3] UNHCR Regional Office for the United States and the Caribbean. “Children on the Run.” Accessed November 20, 2014. http://unhcrwashington.org/children.

[4] U.S. Department of State. “Western Hemisphere: In-Country Refugee/Parole Program for Minors in El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras with Parents lawfully President in the United States.” Last modified November 14, 2014. http://www.state.gov/j/prm/releases/factsheets/2014/234067.htm.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

A Refugee and Parole Program for Central American Minors

November 20, 2014