On April 9, 2020, the Federal Reserve took the unprecedented step of establishing a Municipal Liquidity Facility (MLF) that will offer up to $500 billion in lending to states and a handful of cities and counties.

Both the substance and the speed are welcome given the crushing impact health care, extraordinary public expenditures, and lost revenues are having on state and local finances. However, the MLF’s proposed eligibility criteria unintentionally deepen what are becoming disturbing and obvious racial disparities of COVID-19.

As initially proposed, the Fed’s MLF facility will support lending to U.S. states and the District of Columbia, U.S. cities with a population exceeding one million residents and U.S. counties with a population exceeding two million residents. The population requirements mean that, unless the Fed revises the eligibility criteria, only ten cities and fifteen counties across the country have direct access to the MLF.

In particular, none of the thirty-five most African American cities in America meets the Fed’s criteria for direct assistance. They will be forced to go through their state government and may be limited by that state’s ability to access funds compounded by the state politics.

While the Fed’s criteria were surely motivated by a desire to make loans quickly, the consequences are significant. As a result of both urban/rural and racial politics, many of the largest metropolitan areas lack single jurisdictions that meet the Fed’s criteria for assistance. The entire metropolitan statistical areas of Atlanta, Baltimore, Boston, Pittsburgh, and Detroit all fail this test. Not a single city or county in Ohio, Georgia, or New Jersey (America’s densest state) qualify.

For every ten percent more Black the city’s population, it is ten percent less likely to qualify for the Fed’s program.

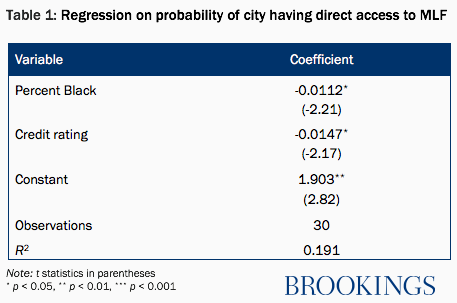

To show how powerful the racial impact of the population criterion is, we looked at the interaction between city size and the African-American population share, controlling for credit rating. The result (shown in Table 1) finds a strong statistical correlation: For every ten percent more Black the city’s population, it is ten percent less likely to qualify for the Fed’s program.

Interestingly, given the Fed’s interest in making loans only to solvent entities, the 10 largest cities have a lower average credit rating than the next largest 20, so the Fed’s criterion is increasing its risk (at least as judged by credit rating agencies).

We are not suggesting that the Fed had racist intentions when setting this limit. To the contrary, everything suggests the Fed was just acting quickly in unprecedented area – the Fed has long objected to aiding municipal and state governments for good reason. Quick actions can have unintended consequences, and the Fed has time to fix this one.

Avoiding discriminatory outcomes, even when there are no malicious intent, is a critical part of anti-discrimination policy. When the Fed policed consumer lending for problems it used a test called disparate impact. The Fed defined disparate impact as occurring, “when a lender applies a racially (or otherwise) neutral policy or practice equally to all credit applicants but the policy or practice disproportionately excludes or burdens certain persons on a prohibited basis.” It should apply that logic to the eligibility criteria for MLF as well.

With the increasing evidence of the disproportionate impact that the COVID-19 is having on Black and other communities of color, it will be important for policymakers to actively use an equity scorecard to ensure that, at the very least, their actions do not exacerbate existing inequities and at best, correct over the very near term the disparities that do exist. Hence, the Fed should be thinking about how to modify the MLF so that what is obviously a rescue operation does not turn into something more familiar: a policy operation that disadvantages Black and brown populations.

We know that direct access to the Fed’s liquidity facility provides security and independence to the cities that currently qualify under the MLF. They can continue to manage their own finances and debt needs. The MLF is not a cure-all, it has limitations on the size of support and the types of debt instruments it will take, as well as only providing support for funding of two years or less in duration. Every other city must go through their Governor’s office, hands outstretched, to ask for assistance.

The Federal Reserve’s decision-making is supposed to be independent of short-term or partisan politics. But the Fed’s policy actions do not exist in a neutral racial context and political reality. In the U.S. the reality is that state Governors favor constituencies and geographies.

So what can the Fed do?

There are several possibilities. One potential solution would be for the Fed to expand the MLF to the 50 largest cities (down to New Orleans at just under 400,000) and 50 largest counties in America. Another would to be to accept notes that meet the MLF’s strict criteria from any municipal issuer directly; why force anyone to go through the governor’s office?

The history of American urbanization is fraught with racially biased policies. The federal government’s decision of where to allocate credit plays a central and abhorrent role: the term redlining comes from federal mortgage credit program in the Great Depression and its aftermath. We know that majority Black cities do not receive the same level and types of investment that majority white cities do. And now, in addition to the disparate impact of COVID-19 on Blacks and communities of color, Black-owned businesses are at greater risk from the disease and recession as our colleagues Andre Perry and David Harshbarger document. Adding heavily majority-minority cities and counties to the disadvantaged list when creating the MLF would perpetuate an ugly history.

It’s time to modernize the policy playbook and think through the equity impacts of the MLF. The Fed has acted to remedy discrimination in the past. Luckily, the Fed has time to show how it can do so here, too.