Each month, many thousands of workers across the U.S. lose their jobs, while others find themselves newly employed. The net number of jobs created or lost in all this activity is an important indicator of the nation’s economic health. But the raw number of jobs created or lost from one month to the next doesn’t say much about the underlying economy. Rather, many of these month-to-month changes are the result of predictable seasonal fluctuations. For example, the fact that the last ten Januarys witnessed the economy shedding over 2.5 million jobs is simply retailers slowing down after the holidays and says nothing about broader economic performance.

This year’s monthly job gains and losses can indicate how the economy is doing once they are corrected to account for the pattern we already expect in a process called seasonal adjustment. The approach for this seasonal adjustment that is presently used by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) puts very heavy weight on the current and last two years of data in assessing what are the typical patterns for each month.

In my paper “Unseasonal Seasonals?” I argue that a longer window should be used to estimate seasonal effects. I found that using a different seasonal filter, known as the 3×9 filter, produces better results and more accurate forecasts by emphasizing more years of data. The 3×9 filter spreads weight over the most recent six years in estimating seasonal patterns, which makes them more stable over time than in the current BLS seasonal adjustment method.

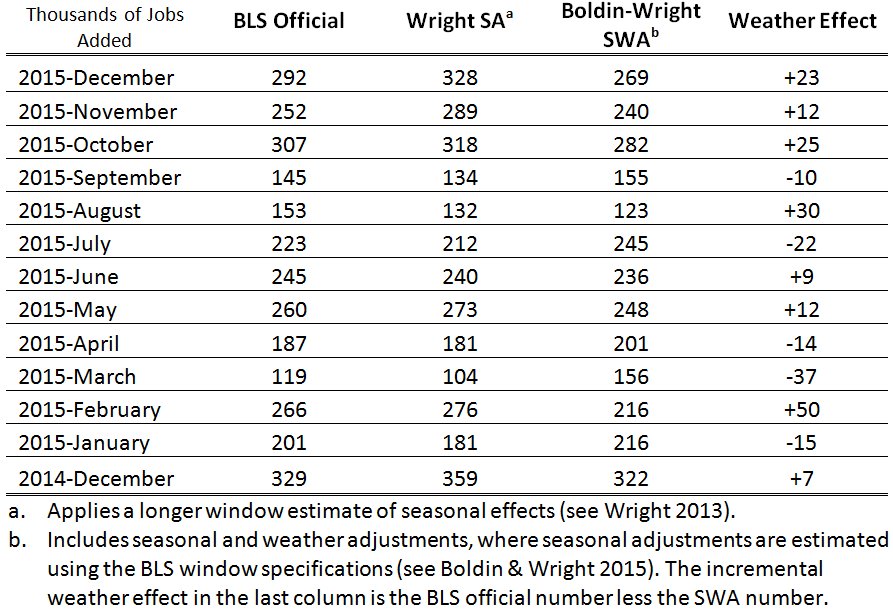

I calculate the month-over-month change in total nonfarm payrolls, seasonally adjusted by the 3×9 filter, for the most recent month. The corresponding data as published by the BLS are shown for comparison purposes. According to the alternative seasonal adjustments, the economy gained 328,000 new jobs last month, 36,000 more jobs than the official total. Data updates released today for prior months also reveal some differences between my figure and the official job gains numbers from prior months. While the official BLS numbers for November were updated to 252,000 new jobs, my alternative adjustment indicates that 289,000 new jobs were added, 37,000 more than the official number. The discrepancies between the two series are explained in my paper.

In addition to seasonal effects, abnormal weather can also affect month-to-month fluctuations in job growth. In my paper “Weather Adjusting Economic Data” I and my coauthor Michael Boldin implement a statistical methodology for adjusting employment data for the effects of deviations in weather from seasonal norms. This is distinct from seasonal adjustment, which only controls for the normal variation in weather across the year. We use several indicators of weather, including temperature and snowfall.

For the month of December, higher-than-average temperatures appear to have had a significant effect on jobs, with warmer weather likely boosting construction employment above its seasonal norms. Our weather-adjusted estimate of 269,000 new jobs factors out the effects of unusual weather, which we estimate were roughly 23,000 new jobs.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

292,000 new jobs added in December? Alternative measures give different picture

January 8, 2016