The following brief is part of Brookings Big Ideas for America—an institution-wide initiative in which Brookings scholars have identified the biggest issues facing the country and provide ideas for how to address them. (Updated January 31, 2017)

Whether President-elect Donald Trump and his advisers know it or not, a complex challenge in the field of intelligence law will confront the new president almost immediately when he takes office: The legal authorization for one of the intelligence community’s most important collection programs is set to expire on December 31, 2017.

Whether President-elect Donald Trump and his advisers know it or not, a complex challenge in the field of intelligence law will confront the new president almost immediately when he takes office: The legal authorization for one of the intelligence community’s most important collection programs is set to expire on December 31, 2017.

The failure to reauthorize the law at issue—Section 702 of the FISA Amendments Act—would deal a body blow to the intelligence community. Yet the conduct of Mr. Trump as a candidate and immediately following his election will greatly complicate his task as president of bringing about its reauthorization. In the current environment, it will require care and prudence on the part of the new administration to put itself in a position to ask for and receive reauthorization of 702, since many people, based on the candidate’s own words and actions, will reasonably fear abuses by intelligence agencies under his control.

But for Mr. Trump’s election, the debate over 702 reauthorization was poised to be a relatively easy one. The law—which clarifies that the normal warrant requirements of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act do not apply when the National Security Agency or the FBI is conducting surveillance of non-U.S. persons reasonably believed to be outside the United States—is a critically important tool.

Broadly speaking, it permits the intelligence community to target certified categories of foreign communications for collection as they pass through U.S. servers and tech companies. Information derived from the 702 program, sometimes known as PRISM, comprises a large part of the President’s Daily Brief. Intelligence community insiders unanimously view 702 as one of the most important available instruments for foreign intelligence signal collection in the United States. The reason is that the FISA warrant requirement was never meant to apply to non-American targets overseas, and its cumbersome procedure—designed to protect civil liberties domestically—is simply incompatible with the volume of foreign intelligence information the United States collects abroad and the aggressiveness with which it does so. Yet much of this information, because of the dominance of U.S. technology companies in the global information architecture, now passes through servers in the United States. Without 702 to relieve the intelligence community of the strict terms of FISA, a lot of collection would grind to a halt.

What’s more, despite the anxieties expressed over 702, particularly in the wake of the Edward Snowden leaks, there have been no serious allegations that the 702 program has been the subject of abuse, and there is a lot of evidence that it has been used responsibly. There is strong bipartisan support for the program among members of both the House and Senate intelligence committees. As of November 7, in other words, the only serious question about 702 reauthorization was whether it would be a “clean reauthorization”—one without significant changes—or whether Congress would seek to build in some limited number of additional protections.

Mr. Trump’s election, however, substantially complicates the reauthorization picture. This is a man, after all, who campaigned promising abuses of power involving the intelligence community: spying on people because of their religion, torture, and retaliation against political opponents. This is also a man who, after the election, has left open the possibility of removing FBI director James Comey because the director concluded a criminal investigation without bringing charges against Mr. Trump’s opponent, Hillary Clinton. We often think about 702 as an NSA authority, but it is also to a significant degree an FBI authority. Thus, the person and the integrity of the FBI director is critically important to the integrity of the program. When a president openly contemplates violating the strong customary norm against firing the FBI director, based on the president’s predetermination that a citizen is guilty of a crime absent evidence, and replacing that person with someone acceptable to himself, it inevitably casts 702 in a very different light.

Unless and until Mr. Trump changes the environment with respect to the pervasive and justified anxieties about his intentions, 702 reauthorization may be extremely difficult, if not impossible. Even the Obama administration, which was not accused of significant abuses of intelligence authorities and which always struck a measured tone on those authorities, increasingly struggled to pass FISA-related laws. The USA Freedom Act, the last set of major changes to FISA, passed only after a divided Congress actually let an intelligence program lapse for a period of time. If Mr. Trump continues to send erratic and dangerous signals, it is not hard to imagine a bipartisan coalition in the House of Representatives preventing 702 reauthorization. It is even easier to imagine a group of 41 senators blocking consideration of a reauthorization bill in the Senate, either as an end itself or as a way of forcing Mr. Trump to stop some other activity or give in on some other matter.

Remember that inaction here produces repeal. The sunset provision requires positive congressional action for 702 to persist.

We might chalk all this up to the ordinary rough and tumble of politics, except for the fact that we need 702 and our security cannot afford even a temporary lapse. The Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board concluded that 702 “has enabled the U.S. government to monitor . . . terrorist networks in order to learn how they operate and to understand how their priorities, strategies, and tactics continue to evolve” and notes that 25 percent of the NSA’s reports involving international terrorism rely on data from the program. President Obama’s review group following the Snowden revelations concluded that 702 “has clearly served an important function in helping the United States to uncover and prevent terrorist attacks both in the United States and around the world.” This is one of the bread-and-butter programs of U.S. signals intelligence, and the incoming president must not let fears about his intentions or personality cause it to evaporate.

The burden is entirely on the new administration, and on Mr. Trump personally, to instill in Congress and in the public the kind of confidence that will make reauthorization possible. To this end, the new administration should take the following five steps:

First, the president-elect should immediately cease the speculation about replacing Director Comey. Comey is not a popular man these days in either political party, but his removal for refusing to indict Hillary Clinton would constitute the most dramatic politicization of the intelligence community since the Watergate era. Though the president undoubtedly has the raw constitutional authority to fire Comey, it would be a grave breach of the presidential obligation to take care that the laws be faithfully executed to fire an investigator for concluding that a U.S. citizen had committed no crime. If President-elect Trump wishes for Congress to continue reposing in him the awesome collection powers associated with 702, he immediately must cease contemplating such abusive behavior.

Second, the president-elect needs to choose Justice Department leadership of genuine stature and bipartisan regard. The first line of oversight of all FISA programs, outside the intelligence agencies themselves, is the men and women of the U.S. Department of Justice, who both restrain and represent the intelligence agencies in court. The persons of the attorney general, the deputy attorney general, and the assistant attorney general for national security thus matter a great deal. Are these people whose word—when they make factual representations to the court, Congress, and to the public—matters? Mr. Trump ran a remarkably fact-free campaign. The relationship between the intelligence community and the law, however, must be based on facts and trustworthy personnel. If Congress does not trust the Justice Department’s senior leadership in its intelligence oversight role, and its representation role of the agency in the FISA court system, 702 will die. The selection of Senator Jeff Sessions represents, in this regard, an inauspicious start. The merits of the appointment are beyond the scope of this chapter, but suffice it for the present to say that we can expect a highly partisan fight over his confirmation. And we can expect as well Justice Department comments on 702 matters in the first year of the administration to be received, particularly by Democrats, in light of the fallout from that fight. All of this puts an enormous premium on whom Mr. Trump names for key positions beneath the attorney general.

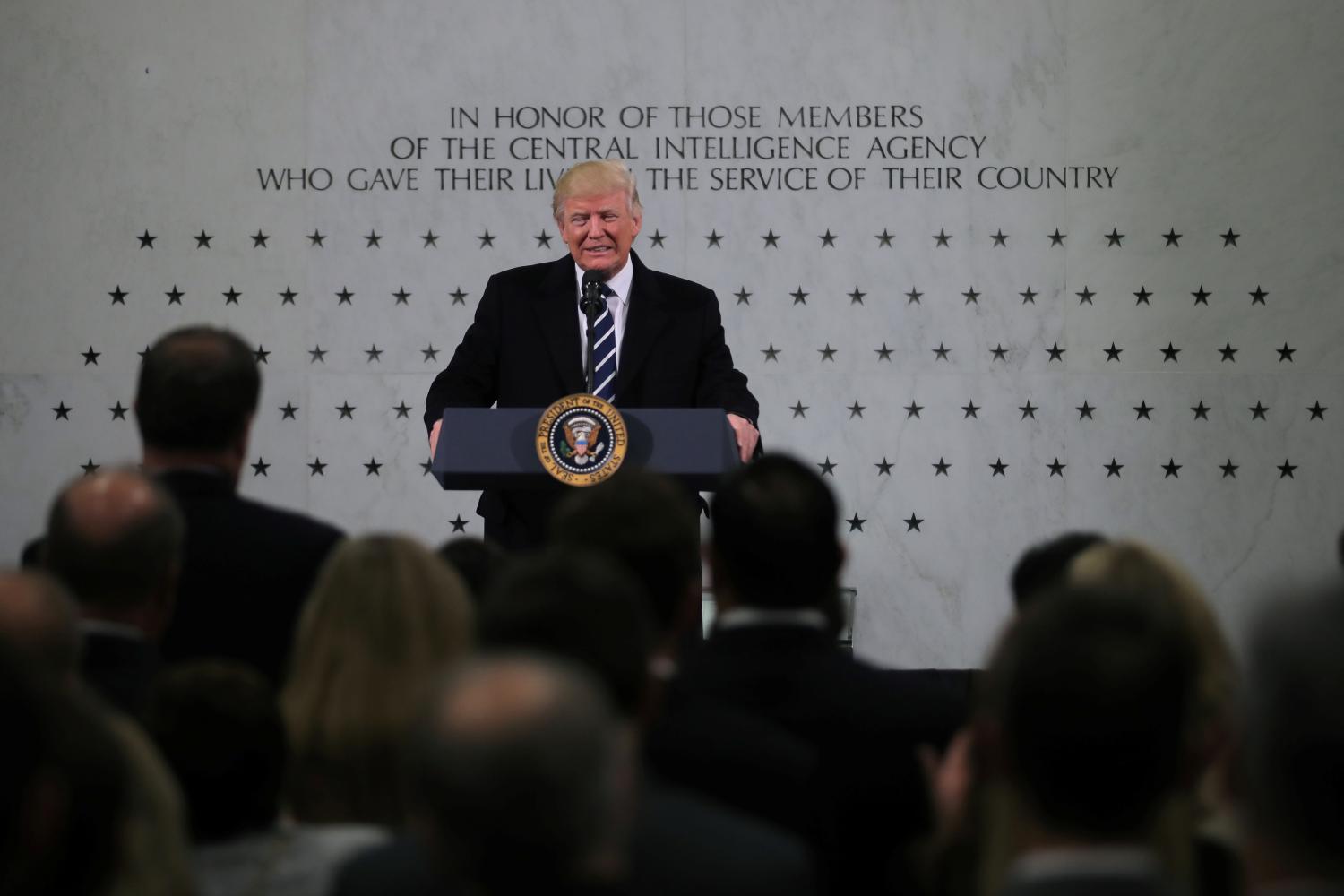

Third, the president-elect needs also to choose a CIA director of genuine stature and bipartisan regard. The Central Intelligence Agency is not the epicenter of the FISA process. But it is the epicenter of a lot of intelligence controversies. And Mr. Trump’s promises, particularly with respect to waterboarding and torture and targeting terrorists’ families, make vivid the possibility of major confrontations over CIA activities. It is hard to imagine that Congress will easily renew authority for major NSA activities in the presence of real doubt as to whether the CIA plans to follow the law. Putting in charge of the agency serious leadership committed to legal compliance is critical to maintaining public and legislative confidence that the intelligence community more broadly, the NSA included, can be trusted with the 702 powers. The selection of Mike Pompeo as CIA director is more promising here than is the Sessions nomination. Pompeo has the regard of a bipartisan collection of former intelligence officials and colleagues on the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence. On the other hand, his views of the early Bush administration CIA interrogation program can be expected to spark serious controversy in the context of his confirmation.

Fourth, the president-elect needs to work with the bipartisan leadership of the two intelligence committees to verify publicly that he has not altered the NSA’s operating authorities or guidance—or, alternatively, that any changes he does make are lawful and prudent. People need confidence, if they are to reauthorize 702, that the NSA they are empowering is the same entity with the same policies and practices that has not abused it in the past. They need to have confidence that the order they are reauthorizing is the regular order. The oversight committees have a critical job in this respect. But the incoming administration does, too. The more changes it makes, and the more it obscures its changes, the less confident people will be.

Fifth, and almost too obvious to mention, the incoming administration needs to assiduously avoid any actions involving the intelligence community that represent any appearance of departure from reasonable public expectations of intelligence community conduct. The early Bush administration took highly aggressive actions that raised serious legal questions. The later Bush administration and the Obama administration moderated those actions notably, with the result that there is now a high degree of consensus among a wide array of analysts about the proper scope of intelligence community activity. While disagreement remains on the precise contours of transparency and oversight, today there is a strong shared sense of where the lines of normalcy are. Actions that push those lines will gravely undermine the confidence on which stands the legislative coalition for 702.

Section 702, in short, is a palatable tool only because we have high confidence in the fidelity both to law and to a certain set of relatively settled expectations about intelligence community behavior. That is, we have high confidence that it is being used responsibly, by responsible people, and for genuine foreign intelligence, not political, purposes. Our president-elect must come to understand that it will survive only as a long as that continues to be the case, and he needs to behave accordingly, or his first year will see the loss of a critically important national security tool.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).