This report is part of the Series on Regulatory Process and Perspective and was produced by the Brookings Center on Regulation and Markets.

With so much happening in Washington, it would be easy to overlook that—halfway through the president’s term—the Trump administration’s deregulatory mission is continuing apace, albeit quietly in the background. Although observers have largely focused on the volume of rulemaking activity under Trump (or, more specifically, the decline in the volume of rules issued—see here and here), I want to pause for a minute to think about process.

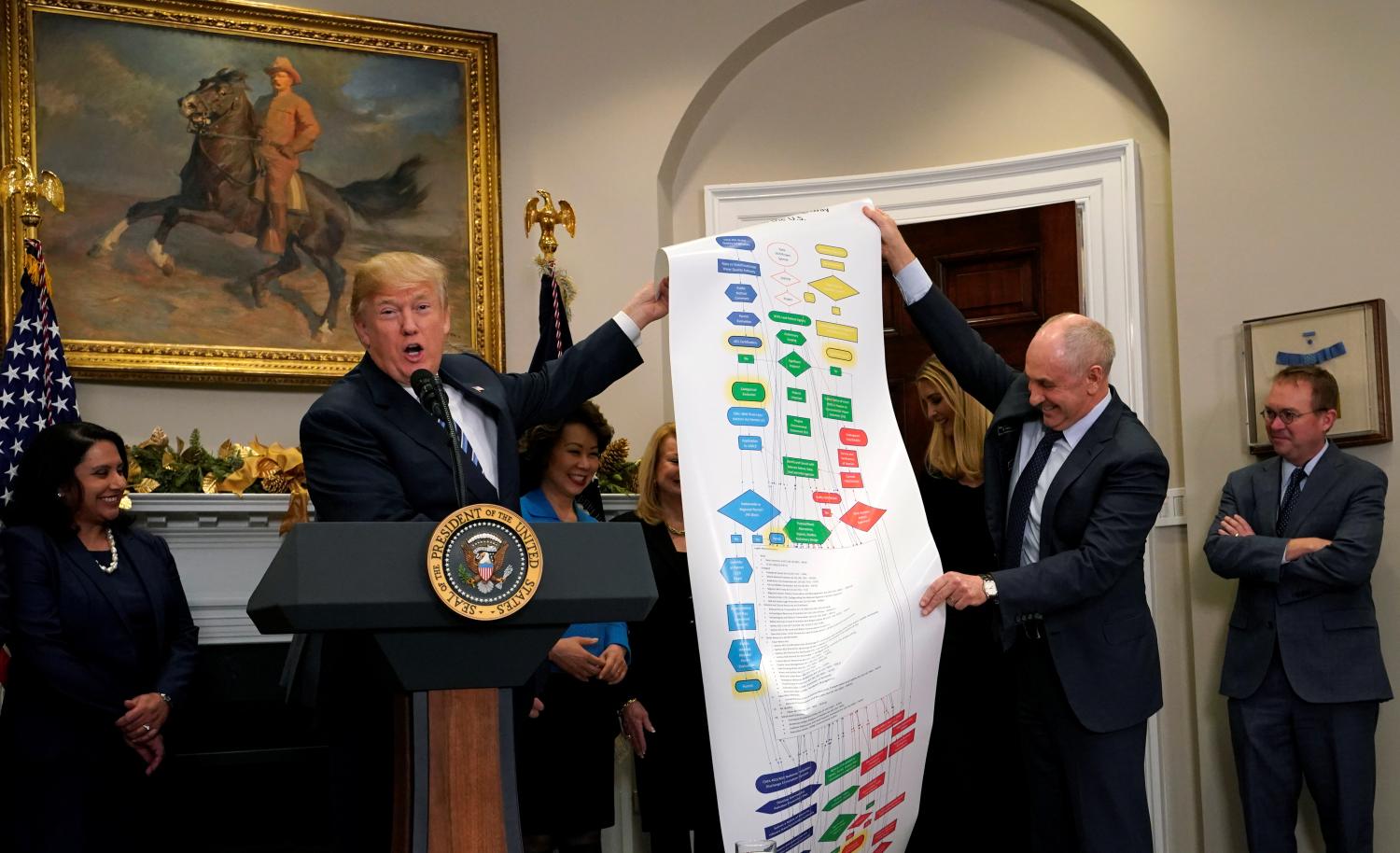

As I’ve written before, rolling back regulation is not easy; it requires time, expertise, and a sustained commitment to see the process through. Procedures matter in rulemaking and there are many opportunities for an agency to misstep. In its haste to achieve deregulatory milestones, the Trump administration has pushed a number of procedural requirements aside, including by:

- Delaying the effective date or compliance date of final regulations issued under the Obama administration;

- Juicing cost-benefit analysis to support the administration’s preferred policy position. Recently this included adopting an assumption that the planet would warm seven degrees by the end of the century—a position starkly at odds with the administration’s stated position on climate change, but that served the short term goal of providing a favorable analytical outcome for that particular rule; and

- Giving limited opportunity for public comment, as the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recently did for a proposed rule to allow a new use for the chemical Oxazolidine. The agency allotted just 15 days for public comment—an amount of time that falls well short of the EPA’s own guidelines (which call for a minimum of 30 days) and the federal recommendation (which calls for 60 days).

What we should make of all this procedural corner-cutting? Why is it happening, and does it matter if Trump fails to follow the rules of rulemaking? I offer three points on how to evaluate this procedural maneuvering.

#1: Corner-cutting is not new, but the Trump administration’s approach is particularly worrisome

The Trump administration has clearly been manipulating the procedures associated with rulemaking in order to advance its policy agenda. For instance, in its regulatory analyses, the Trump regulatory agencies have adopted a lower social cost of carbon to make it harder to offset the costs imposed by new environmental protections. But this administration is hardly the first to engage in such behavior. When the Obama administration introduced the social cost of carbon calculation back in 2013, it was also accused of playing politics in the opposite direction: introducing a new factor into analyses that stacked the deck in favor of stringent environmental protections. Much as we would like to think of the regulatory process as a neutral and administrative one, it has never been free of politics.

Much of the commentary on Trump’s legacy on administrative politics—from both the left and the right—centers on the administration’s lack of respect for the rule of law.

Nonetheless, we should not accept the current administration’s approach to procedure as typical political jockeying. Much of the commentary on Trump’s legacy on administrative politics—from both the left and the right—centers on the administration’s lack of respect for the rule of law. Procedural corner-cutting falls firmly under this banner and feeds into a broader narrative that the institutions as a matter of course. This has the potential to undermine public confidence in both the regulatory process and democracy writ large. There are also implications for policy quality, as I explain below.

#2: The Trump administration’s personnel policies may be to blame

Trump’s bureaucracy has been plagued by staffing troubles from the outset. Not only has he had difficulty getting nominees through the Senate confirmation process, his administration has also faced high turnover among those officials that have been installed. Many appointees also lack substantive expertise in their policy areas. Taken together, these management issues exacerbate the pathologies of corner-cutting; some appointees may choose to undercut the system rather than work through it, while others may be too inexperienced to appreciate the procedural intricacy and value of process in rulemaking.

Personnel issues may also explain why the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA)—the White House clearinghouse for agency rulemakings—has not put the kibosh on Trump’s procedural maneuvers. On the one hand, with only 45 career officials and one Senate-confirmed political appointee, OIRA may have too few staff to effectively crack down on these practices.1 On the other hand, how OIRA deploys its limited resources is itself a political decision. In a recent speech, OIRA Administrator Neomi Rao highlighted the office’s focus on eliminating the inappropriate use of guidance documents. While this is important, focusing on it may come at the expense of other procedural issues. For instance, OIRA has been criticized for failing to rigorously analyze agency cost-benefit analyses, particularly when those analyses favor the administration’s stance (see here and here). Ultimately, how OIRA targets its review resources is subject to political influence, from both the administrator and higher-ups in the White House.

The sum total of these personnel problems may be felt in terms of policy and not just procedure. Capacity deficits in Trump’s agencies may mean that not only are agencies pushing through regulations without regard to the proper procedures, but also that the quality of the substantive work being produced is lower. That means agencies may be producing rules that are not as coherent or able to effectively achieve the intended policy outcomes.

#3 Cutting corners is not a good strategy if Trump wants durable policy change

The irony is that while cutting corners may offer Trump’s agencies a quick fix—netting headlines and seemingly advancing the deregulatory agenda—it’s not a winning strategy for the administration over the longer term. There are two reasons for this.

First, the courts have repeatedly rebuffed Trump’s agencies on deregulatory cases. And, as my colleague Connor Raso has argued, these court rulings are likely to establish new case law that makes it harder for agencies to deregulate in the future. This body of law, in turn, should encourage interest groups to increasingly rely on the courts as a way of keeping deregulation at bay. This means that continued corner-cutting is likely to engender more lawsuits and, possibly, more overturns for agencies.

Second, the Democrats’ midterm takeover of the House portends increasing oversight of this administration. Failure to follow rulemaking procedures is low-hanging fruit for Democrats eager to demonstrate their oversight prowess—it certainly has been in the past. This means shortchanging procedures is likely to become a political liability for the administration in the coming months.

The author did not receive any financial support from any firm or person for this article or from any firm or person with a financial or political interest in this article. She is currently not an officer, director, or board member of any organization with an interest in this article.

-

Footnotes

- OIRA does not review all draft regulations, but only those from executive branch agencies, and, even then, only reviews about one-third of regulations produced by those agencies. This means that from a structural perspective, OIRA’s purview is inherently limited.