This post was updated on March 1 to reflect South Carolina’s primary results in favor of former Vice President Joe Biden.

How will Sanders, Biden, Bloomberg, and others hold up among the full range of Democratic voters?

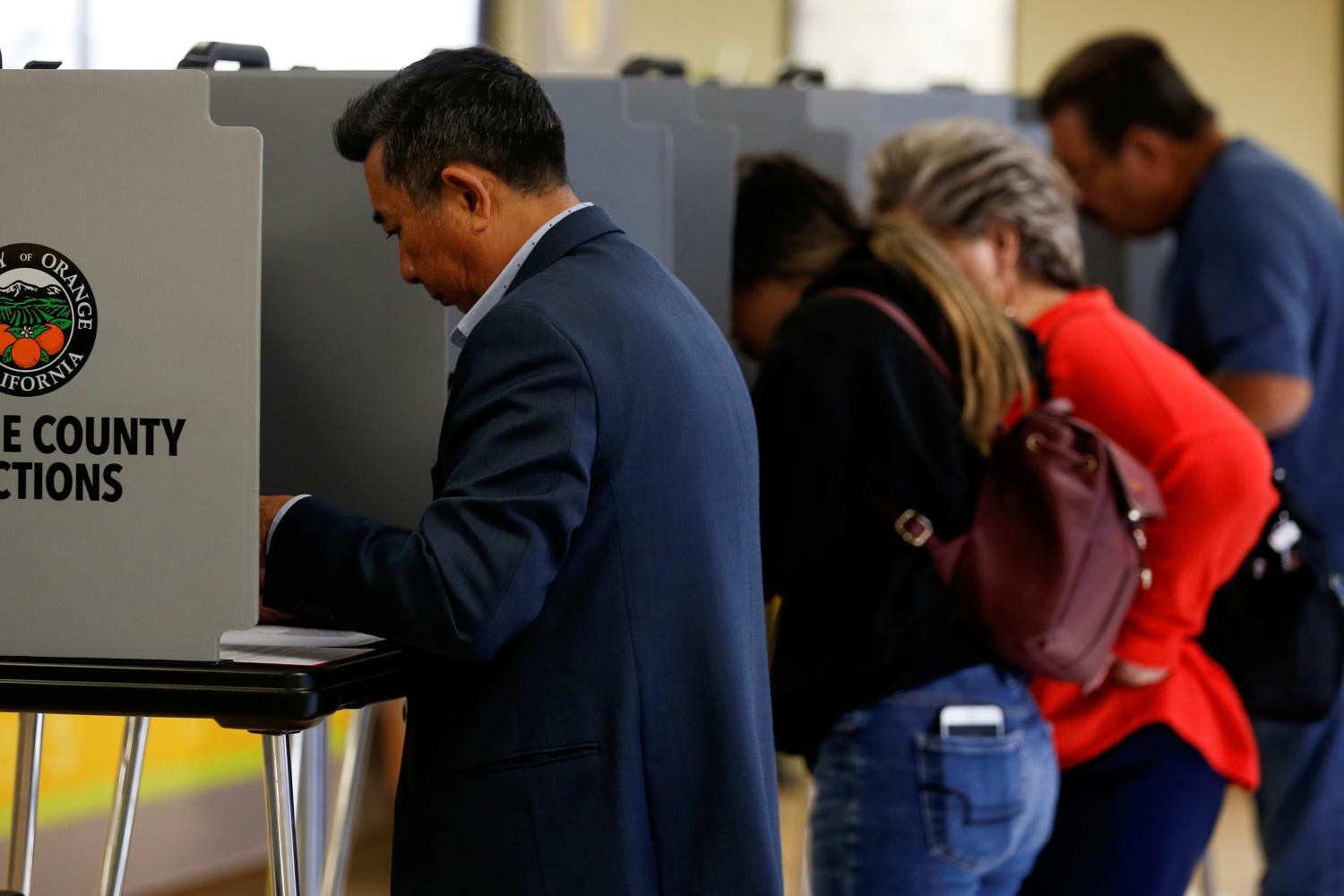

After a getting a taste of Democratic voter preferences from a handful of small and unrepresentative state primaries and caucuses, the main event—Super Tuesday—is upon us. The results from these primaries should provide a clearer picture of how the presidential candidates will fare nationally. Not only do these states provide the biggest single-day delegate haul of the primary season (one-third of all pledged delegates), they also reflect a broad demographic range of voting blocs.

The voting preferences of different race-ethnic groups across the country will be especially important. In light of his impressive showing in South Carolina, will former Vice President Joe Biden continue to marshall strong support from the Black electorate? Will Senator Bernie Sanders continue to make inroads among Latino or Hispanic voters? How will the white vote—especially moderate whites—play out now that former New York City mayor Mike Bloomberg is on the ballot?

It’s useful to categorize the Super Tuesday states in terms of the broad regions where they are located. Seven of the 14 states—nearly half of the day’s delegate count—are in the South, led in size by Texas and followed by North Carolina, Virginia, and Tennessee (each larger than any of February’s caucus and primary states) as well as Alabama, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. These states are less white and have larger Black shares of their populations than the nation as a whole.

However, Super Tuesday states outside of the South represent more pledged delegates than those in it. This is due to the presence of California, which moved its primaries to earlier in the year after the 2016 election. As a consequence, California and the other western-region primary states (Colorado and Utah) will reveal, more so than Nevada did, how candidates will fare among Latino or Hispanic voting blocs.

The remaining states (Massachusetts, Maine, Vermont, and Minnesota) house sizeable older white populations. They will provide a glimpse of how far Iowa and New Hampshire’s results—which featured strong showings from Sanders and former South Bend, Ind. mayor Pete Buttigieg—extend to states with similar demographics.

A test for Biden in the South

On Super Tuesday, Joe Biden’s perceived strength among Black voters (especially in the South) will be put to its greatest test. The seven southern states are not mirror images of each other, but five of them—North Carolina, Virginia, Tennessee, Alabama, and Arkansas—have sizeable Black populations which comprise the largest racial minorities in the states (See Table 2A). The clout of African Americans here is crucial: As shown in Table 2B, Black participation in these states’ 2016 Democratic primaries ranged from 26% of voters in Virginia to 54% in Alabama.

Biden can draw hope from the fact that Sanders did not perform well in the South in 2016. Among that year’s two major contenders, former New York senator Hillary Clinton bested Sanders in the popular vote in every one of these states, both overall and especially among Black voters. Clinton’s share of the Black vote ranged from 80% in North Carolina to 91% in Alabama. She also beat Sanders among whites in each of these states except North Carolina.

Texas is the only one of these southern states in which the Black population is outnumbered by the Latino or Hispanic population. Still, in 2016, the Black electorate there voted for Clinton over Sanders by 83% to 15%. Clinton also bested Sanders among the state’s Latino or Hispanic population (71% to 29%) as well as whites (57% to 41 %), to take Texas overall. These results should give Biden confidence, alongside a recent University of Houston poll showing him beating Sanders among Black voters in the state and tying him overall.

The one southern Super Tuesday state that Sanders did win in 2016 was Oklahoma, a state with a relatively small Black population. Clinton triumphed among Blacks voters here (71% to 21%), while losing substantially among whites (36% to 56%).

One might draw parallels between the electoral appeal of Joe Biden and Hillary Clinton, both of whom are associated with Democratic presidencies that were highly regarded by Black voters. Yet even if Biden does well with Black voters in these southern Super Tuesday states, he will face tougher competition from Sanders and others for the other voting blocs there.

Can Sanders keep momentum in California and elsewhere?

With a plurality of delegates up for grabs, states in the West, Midwest, and New England will either confirm or reverse the results from the earlier “litmus test” primaries and caucuses where Sanders was crowned a front-runner.

All eyes will be on California, a state Sanders narrowly lost to Clinton in 2016. California’s population is the most diverse Super Tuesday state of them all, with a Latino or Hispanic population that dominates other race-ethnic minorities (See Figure 3A). A key question will be how strongly Sanders holds up among these voters.

Sanders won 54% of Latino or Hispanic voters in this year’s Nevada caucuses, and in 2016, he was in close competition with Clinton for this bloc in California (42% vs 46%), according a poll taken just before the primary. A positive sign for Sanders comes from a recent University of California, Berkeley poll that has him leading all candidates for the Latino or Hispanic vote, at 51%. For now, at least, his visible efforts to appeal to these voters show signs of paying off.

In California and the two other western states, Colorado and Utah, the competition for white support will be intense. Sanders won the latter two states in 2016 and came in first in this year’s Nevada caucuses among whites. And in a recent California poll, he has a healthy lead over his nearest competitor, Senator Elizabeth Warren, both overall and among whites. This is after his 2016 losing effort there, when he ran neck and neck with Hillary Clinton for white voters. Still, with the wild card of Mike Bloomberg now in the race and potential strong showings from Warren, Buttigieg, and Biden, the white vote may not break for Sanders the way it did in Nevada.

The last tranche of Super Tuesday states—Massachusetts, Maine, Vermont, and Minnesota—will also provide clues as to how the addition of Bloomberg might have affected earlier results in the nearby states of New Hampshire and Iowa. The presumption is that Sanders will do well in Maine and in his home state of Vermont, as he did in 2016 against Clinton. But Senator Amy Klobuchar should give him a fight in her home state of Minnesota. Massachusetts, the most diverse of these whiter Super Tuesday states, might be more difficult for Sanders, who narrowly lost to Clinton there in 2016 and faces a challenge this year from the home-state senator and fellow progressive Elizabeth Warren.

The road beyond Super Tuesday

There is no doubt that Super Tuesday’s results will add some clarity to the Democratic candidate field, though potential variations will likely convince several contenders to remain in the race. This will be the case for Biden if he does very well in southern states and better than expected elsewhere. A stronger than anticipated showing by candidates other than Sanders among whites and perhaps among Latinos or Hispanics in the West could place a temporary pause on the Vermont senator’s surge to the nomination.

This places greater emphasis on the states that lie ahead. The rest of March’s primaries feature states with demographic attributes that are more diverse than February’s primary and caucus states but less so than Super Tuesday’s (See Figure 4). In fact, compared to each stage of this year’s primary trail, the rest of March looks much more like America as whole than any other part of the calendar (Download Appendix Table).

Post-Super Tuesday will highlight one area of the U.S. where voters haven’t had their say yet: the industrial Midwest. These states have high shares of non-college-educated whites, and include Michigan and Missouri (March 10), along with Ohio and Illinois (March 17). Other influential states with primaries in March are Washington, Arizona, Florida, and Georgia. By the end of March, 65% of pledged delegates should be selected.

However, if multiple candidates are still in play, contests in April, May, and June could still decide the winner. Louisiana and Wisconsin will hold key primaries in the first week of April, and a Northeast-Atlantic coast juggernaut of states that includes New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Delaware, Connecticut, and Rhode Island should make a statement on April 28. The final 13% of delegates will be selected in the May-June time frame, mostly from whiter states in the nation’s heartland. But if the primaries still matter in June, the racially diverse states of New Jersey and New Mexico could be influential.

This year’s parade of Democratic primaries is heavily front-loaded with a diverse array of Super Tuesday states that are poised to show which demographic blocs favor which candidates. Importantly, they will underscore the extent to which Joe Biden can ride a wave of popularity among the party’s significant Black voting bloc, and if it is enough to stay in the race. They will also determine whether Bernie Sanders can extend his strong early-primary support among Latinos or Hispanics and whites to large enough swaths of the country, and continue as the party’s unambiguous front-runner.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).