Executive summary

Executive summary

The international liberal order based on collectively securing peace, promoting development, and protecting human rights is facing a major stress test. With the decline of U.S. leadership, a weakening Europe, and the rise of authoritarian China and Russia, the future of the liberal order depends on newer democratic powers picking up the slack. Leading players such as India, Brazil, South Africa, the Republic of Korea, Indonesia, and Mexico are capable of playing a more active role to sustain a global cooperation agenda favoring open democratic societies. Many of these countries, however, face significant political and economic challenges of their own. If geopolitical competition intensifies, they may choose to sit on the fence or accept lowest common denominator outcomes for the sake of avoiding outright economic or military conflict. Liberal democracy and human rights, in this scenario, will erode further.

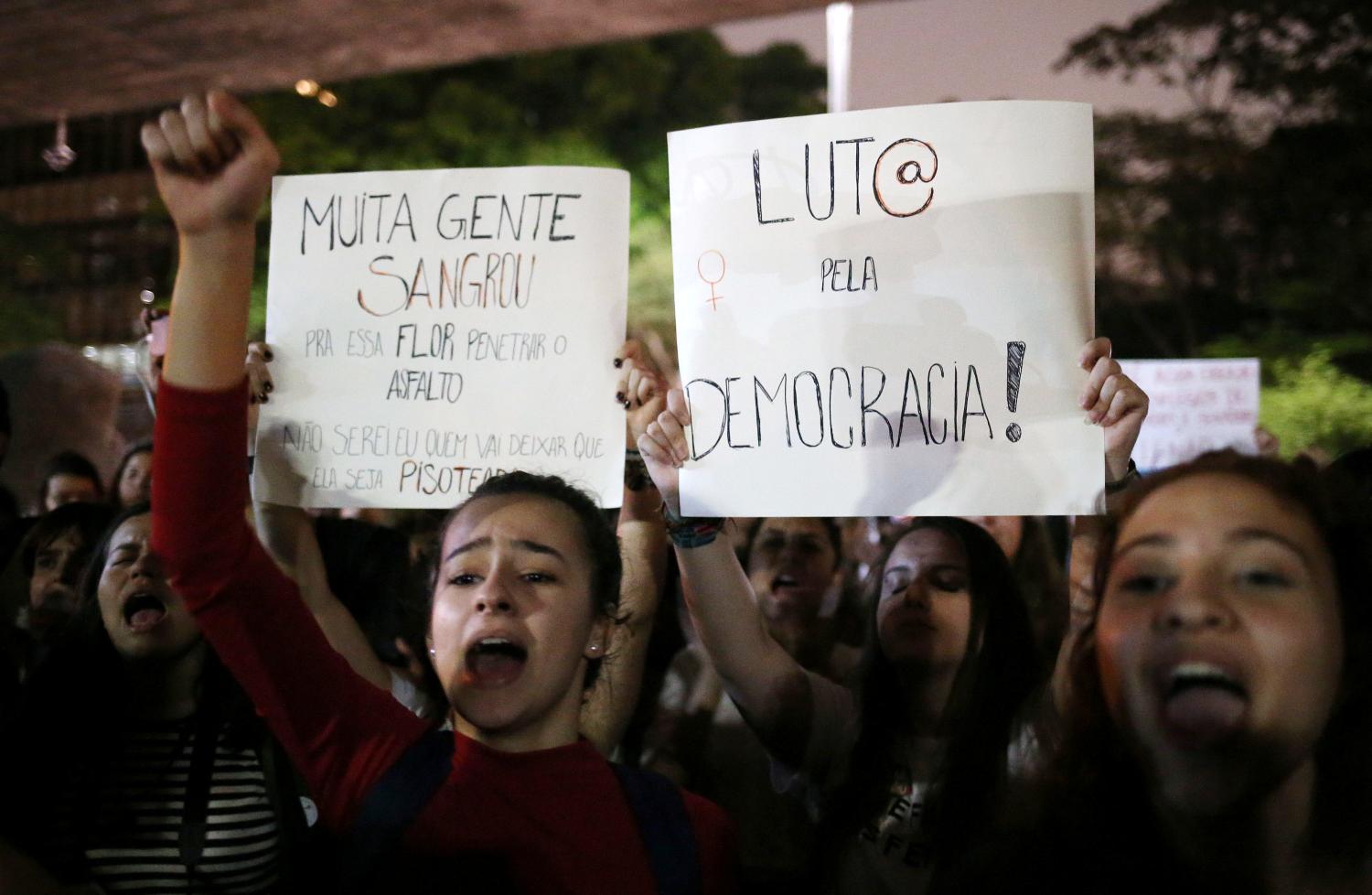

A close look at the evolution of these six middle power democracies reveals a turning away from more ambitious goals of regional and global influence. In Brazil and South Africa, the traditional political order has nearly collapsed under the weight of revelations of deep structural corruption and economic downturns. Mexico’s foreign policy is returning to its traditional noninterventionism as it struggles to maintain equilibrium in the face of direct challenges to its trade and migration relationship with the United States and escalating violence and corruption. South Korea, after weathering a major constitutional crisis that led to the jailing of former President Park Geun-hye, is consumed by the threat of war on the Korean Peninsula. Indonesia is coping with a more muscular version of political Islam and a retrenchment in its regional ambitions. Only India, which also has chosen a more nationalist and populist approach to governing at home, is raising its foreign policy game, for example by contesting China in the Indo-Pacific.

Middle power democracies, like the six reviewed in this essay, have a potentially positive role to play if they can revive their once promising paths to sustainable democratic development. As they have mostly benefited from the upside of economic globalization and democratization, they should also become more responsible stewards and shapers of our interdependent system. They now need to step up and share the burden of managing a more multipolar world that aligns with their own democratic values and interests. They can do so by contributing more resources to international institutions that uphold universal values and protect the global commons, support implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals, defend civil society and independent media from growing attacks on their work, build cross-regional coalitions to block the growing trend toward zero-sum nationalism, and proactively share the burden of good global governance.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).