Student loan debt is back in the news with the launch of a campaign by progressive education advocates, dubbed “Higher Ed, Not Debt,” aimed at aiding borrowers and reducing college costs. A leading voice in this effort is Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, who plans to introduce legislation that would allow borrowers to refinance their existing loans at lower interest rates.

Sen. Warren’s proposal has some intuitive appeal, as she describes it: “The idea is pretty simple. When interest rates are low, homeowners can refinance their mortgages. Big corporations can swap more expensive debt for cheaper debt … But a graduate who took out an unsubsidized loan before July 1 of last year is locked into an interest rate of nearly 7 percent. Older loans run 8%, 9% and higher.”

This plan also has obvious appeal in light of frequent media coverage about households struggling to repay student loan debts. But it represents a fundamental shift from a federal lending program that has historically acted more or less like a bank—with the goal that student loans will be roughly budget neutral in the long run—to something that more closely resembles an entitlement program. Allowing borrowers to refinance their loans at below-market rates with the government would lead to a potentially large increase in the cost of the program, which would have to be funded through a general increase in interest rates or revenue from other sources.

The proposal pursues the latter course, suggesting that loan refinancing could be paid for by a tax increase on wealthy individuals commonly called the “Buffett Rule.” Government programs that redistribute resources, usually from wealthier to less well-off individuals, are not uncommon. And it seems, as the narrative about the proposal suggests, that reducing interest rates on outstanding debts would put money back into the pockets of the households that need it the most. Unfortunately, the plan fails to achieve this objective. In fact, the plan is largely regressive and not the least bit progressive.

Refinancing loans provides the greatest benefit to borrowers with large outstanding debts.[i] This doesn’t seem like such a bad thing until you realize that households with large outstanding debts tend, on average, to be high-income households. Many borrowers who take on large debts do so in order to pursue degrees that lead to high incomes, in fields such as law and medicine. These are not the same households who are struggling financially and are perhaps in need of a bailout.

>We illustrate this point using data from the 2010 Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), a nationally representative survey of U.S. households administered by the Federal Reserve Board. We calculate how much outstanding education debt is held by each household headed by individual(s) aged 25-40, and relate it to the total income of the household.[ii] Households with more debt will receive greater benefits from a reduction in interest rates.

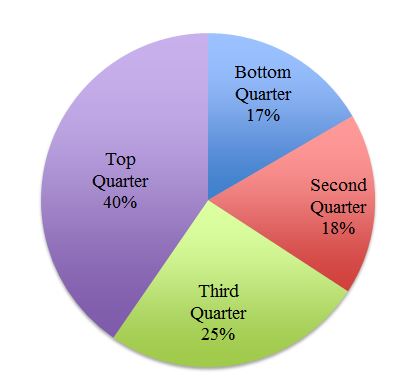

The figure below shows that higher-income households hold a disproportionate share of student loan debt. The richest 25 percent of families hold 40 percent of the student loans, so would receive roughly 40 percent of the benefits of a proposal that allowed all loan debt to be refinanced at lower rates. On the other side of the income spectrum, the poorest quarter of households would receive less than one-fifth of the benefits of such a proposal.

Student Loan Debt is Disproportionately Held by High-Income Families

Source: Authors’ calculations from 2010 Survey of Consumer Finances, households with average age 25-40.

It’s clear that this plan fails to redistribute wealth in a progressive manner, but it also has another problem. Subsidies to education exist in order to encourage changes in behavior that advance society’s goals. For instance, students from disadvantaged households receive Pell grants with the hope that they will be able to enroll in and graduate from college when they would not have otherwise. Subsidies that do not change behavior, as would be the case with loan refinancing, simply amount to wealth redistribution.[iii]

The SCF data make clear that universal refinancing flies in the face of progressive values by benefiting the affluent at the expense of the disadvantaged. To be sure, struggling borrowers would benefit from lower interest rates, but successful college and graduate degree holders would benefit even more. Is there a less blunt instrument to aid those who struggle to make their loan payments without big handouts to the least needy borrowers?

Fortunately, such programs already exist. The federal government offers a variety of repayment plans to student borrowers that cap their payments based on their income. The best-known plans are Income-Based Repayment (IBR) and Pay as You Earn (PAYE). These programs allow borrowers who experience periods of low income to delay making their full payments without harming their creditworthiness, and forgive outstanding loan balances after a certain number of payments.

There is no doubt that these repayment programs are in need of improvement, and President Obama proposed several reforms in his 2015 budget request. A reduction in interest rates for struggling borrowers might make sense as part of the reform debate, perhaps as an alternative to loan forgiveness. But it is clear that providing the same interest-rate cut to all borrowers is about as progressive as providing the same tax-rate cut to all Americans.

[i] In technical terms, the size of the interest-rate benefit is proportional to the outstanding loan balance at the time of refinancing. A mathematical explanation of this proposition is available from the authors upon request.

[ii] Specifically, we restrict the analysis to households with an average age (among the adults in the household) of 25-40. We use this range in order to exclude likely college students as well as older adults who may have taken on education debt to finance their children’s education.

[iii] A policy that enabled refinancing at lower rates for future borrowers could impact their college-going behavior. It is not clear whether Senator Warren’s proposal will apply to future borrowers or only existing borrowers.