“Give me Liberty or give me Death,” proclaimed Patrick Henry in defense of revolution. In many ways, more than a few Republican governors over the past several months have embraced this mantra in criticizing the president’s health care law. They view the law as an affront to basic liberty, and while it would deliver assistance to their constituents that could prevent illness or death, liberty is of greatest import.

Elected officials have the choice of representing the needs or views of those who put them in office or stand on principle to do what they believe is right. Officials often frame their views of the health care law in terms of the latter. Democrats and progressives view the law as a means of opening access to affordable health insurance for more Americans. Republicans and conservatives describe the law as a government overreach that threatens the basic liberties that all Americans enjoy and must retain.

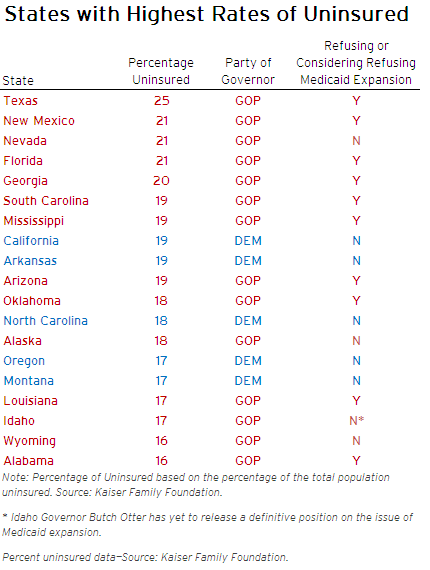

Regardless of the needs of constituents, elected officials’ values appear to be a driving force. In a basic way, states with lower rates of uninsured often have Democratic governors or are traditionally blue states, and states with higher uninsured rates more commonly have Republican governors or are traditionally red states.

For example, 19 states have rates of uninsured at or higher than the national average (16%).[1] Of these states, 14 have Republican governors—including the states with the seven highest rates of uninsured. These states—Texas, New Mexico, Nevada, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, and Mississippi—have 14.5 million individuals without health insurance. More strikingly, these seven states have 29% of the nation’s uninsured.

To be clear, Republican (and Democratic) views on the Affordable Care Act range in intensity. However, many of the nation’s staunchest gubernatorial critics hail from states with higher rates of uninsured. For example, of the nine governors who have publicly refused to expand Medicaid rolls (an option granted to them through the recent Supreme Court ruling), four of those states have uninsured rates higher than the national average. Six other governors from higher-than-average states are openly considering whether to opt out of Medicaid expansion.

Similarly, Democratic governors—many of whom embraced the Affordable Care Act vocally and in initiating early implementation efforts—often hail from states with relatively low rates of uninsured. For example, among the states with the 10 lowest rates of uninsured, seven have Democratic governors—including the four lowest states: Massachusetts, Hawaii, Minnesota, and Vermont. Moreover, 20 of the 24 states with the lowest rates of uninsured cast their electoral votes for Barack Obama in 2008.

Those in most need reject assistance and those with the least need embrace it. What motivates such behaviors? It could be selfless principle. As noted above, Democrats support expanded, near-universal health care, regardless of the marginal impact on their constituencies. Republicans criticize the threats to liberty from the health care law, regardless of constituent benefits. Texas governor Rick Perry (R), who runs a state where a quarter of the population is uninsured, declared in response to the Supreme Court health care ruling,

“Freedom was frontally attacked by passage of this monstrosity—and the Court utterly failed in its duty to uphold the Constitutional limits placed on Washington. Now that the Supreme Court has abandoned us, we citizens must take action at every level of government and demand real reform, done with respect for our Constitution and our liberty.” [2]

Does principle really motivate Democrats and Republicans in the health care debate? No. A more base, self-interested, and political motive drives behaviors over health care. The statistics that appear to suggest that governors are acting contrary to the health care needs of their constituents fail to account for the demographics of the uninsured. While support for or opposition to the president surely affects governors’ views on the health care law, responsiveness to their electoral constituencies plays a central role. University of Rochester professor Richard Fenno describes an elected official’s electoral constituency as a subset of their broader constituency.[3] The electoral constituency is a voting bloc large enough to secure continued electoral success, and politicians primarily cater to this subgroup.[4]

In fact, because the president’s and Democratic governors’ electoral constituencies share demographic characteristics, their pursuit of similar voters motivates support for the law. By contrast, Republicans are successful because of the support of different demographics than Democrats. These electoral forces (not principles such as liberty or empathy) drive elected officials’ positions on health care.

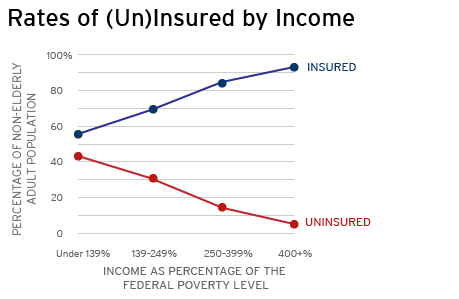

Republicans often depend on white and wealthier voters for electoral success. Democrats’ electoral constituencies have a larger percentage of non-white and/or lower income voters. White and wealthier individuals are insured at dramatically higher rates. The national average for non-elderly uninsured is 18%. The rate for white Americans is only 14%. However, black Americans and Latino Americans are uninsured at rates of 22% and 32%, respectively. As one would expect, there is an inverse relationship between income[5] and the rate of uninsured.

In a basic way, Republican and Democratic governors are not putting principle before politics. Instead, they are capitalizing on the politics of health care and appealing to the voters most important to their electoral needs. While Republican governors have higher percentages of uninsured in their states, their key voters don’t face the same burden. Conversely, voters critical to Democrats’ electoral fates face dramatically higher uninsured rates. Such a basis for policy support—constituency needs—is certainly not a damning trait. Elected officials are seeking to represent a sufficient percentage of their electorate. However, both sides’ political rhetoric of principle and altruism is disingenuous. Concerns about general health and welfare or of government takeovers are window dressing for political pandering.

1 Statistics regarding insurance coverage are all provided by the Kaiser Family Foundation. (Source: http://www.statehealthfacts.org.)

2 “Statement by Gov. Perry on Supreme Court Ruling Regarding Obamacare.” 28 June 2012. Office of the Governor. Austin, TX.

3 Fenno, Richard. 1978. Home Style: House Members in their Districts. Little, Brown: New York.

4 Ibid.

5 Income is defined as categories of percentages of the Federal Poverty Line.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).