A while back, I read a journalistic account of a small island off Italy in which people live to be quite old. Could it be because they sleep late, or drink lots of wine, or live a communal existence, or don’t eat refined sugar? Unfortunately there is no way to know based on the information provided in the article if it is one or more of the lifestyle characteristics the author identified as distinctive, or whether something else is going on. Even the claim of unusual longevity is questionable since there is no birth registry. And taking everything at face value, maybe there are other places in Italy in which people live as long or longer with different lifestyles. But it was a good story, nonetheless.

There were lots of good stories at Education Nation, the annual NBC/Universal talkfest in which I participated last week. My personal favorite was Goldie Hawn (the former actress whose career was built on playing dumb blondes) holding forth on the neurobiology of safe classrooms. Somehow hearing Goldie talk about the amygdala was jarring, but maybe that’s just me.

Not quite so jarring but better fodder for this piece was David Kirp, with whom I was paired in a panel discussion of what it takes to produce a great school district. David expounded on the ideas in his recent book, Improbable Scholars. His story is drawn from the year he spent observing the schools in Union City, New Jersey.

According to publisher’s blurb for the book, Union City offers “a playbook for reform that will dramatically change our approach to reviving public education.” The playbook includes good preschool, a demanding curriculum that teaches thinking not test-taking, parental involvement, support for teachers, a caring environment with high expectations, and the patience to wait for gradual improvements. In David’s words, “there is no pizazz.” Underperforming schools haven’t been closed, teachers haven’t been fired. There are no Teach for America recruits or charter schools or charismatic leaders. Technology plays no special role. The secret sauce is apparently what educators have always wanted, a long-term strategy based on the platitudes they learned in ed school.

I’m going to criticize the approach and conclusions of the book, but not David himself. We spent some time talking both before and after our 20 minutes on stage. I think he is a nice guy — smart, and reasonable. And who can argue with the notion that successful school reform requires a plan and the time to see it through, the communication of high expectations to students, support for teachers to improve their skills, a challenging curriculum, and a good preschool experience for children from low-income families? But he and I come from different disciplines. He is a lawyer and journalist, whereas I am a social scientist. We approach questions of what works in education with different tools and habits of mind. And just like the tale of the island where everyone is said to live to be a 100, David’s story of Union City deserves careful inspection as an empirical claim subject to verification.

The effort to identify what works from natural variation in practices and outcomes has a long history in and out of education. In health care, for example, epidemiologists look for patterns of exposure or activity that are associated with disease. A classic of the genre is the British Doctors Study, published in 1954, which found a statistical association between smoking and lung cancer.

In education, the parallel approach has its longest history in something called the effective schools movement, which arose as a response to the famous 1966 report by James Coleman purporting to show that nearly all of the differences in student achievement in U.S. schools were due to family background. Initially, researchers challenged these findings by identifying schools where poor children were achieving at high levels. A second wave of research went beyond these existence proofs to comparative examinations of the practices in particularly effective and relatively ineffective schools serving demographically similar populations.

In my view, not much has come of effective school research because the distinctions between good and bad schools have been drawn at the level of abstract characteristics rather than processes for generating school improvement that can be replicated. For example, we learn from effective schools research that in good schools there is a shared commitment among staff to the school’s mission and priorities. But we don’t learn the process by which such a commitment can be created. It is sort of like buying a self-help book on running a restaurant and reading that serving good food is really important.

But whatever the limitations of the long history of effective schools research, at least the methodology can be defended in the context of the science of epidemiology. If the studies are implemented well, we know that schools identified as effective are indeed performing at unusually high levels and that comparison schools with less stellar outcomes have similar demographics. In this context, asking what is distinctive about the high vs. the low performing schools is a valid and answerable question, and no different in principle from asking what is distinctive about people who get lung cancer vs. similar people who don’t.

Now let’s look at Union City, NJ. It is a small town in land mass (about a square mile) and population (about 65,000), but it is far from a typical American small town in that the population is overwhelmingly Hispanic (85%). Four out of five families speak Spanish at home. A lot of recent immigrants are Ecuadorian. Blacks are a very small part of the population (5%).

Union City is one of several small towns just across the Hudson river from New York City that were separated by open land when they were founded as villages in the 18th century but now seem an entirely arbitrary political division of a continuous sprawl of urban streets. There are 14 other NJ towns within 5 miles of Union City, including the abutting towns of Weehawken, West New York, and Jersey City. None have the population characteristics of Union City. In particular, only West New York of the surrounding communities has a majority Hispanic population.

From a comparative perspective I wonder why Kirp chose to base a playbook for reviving public education on a school district that is so demographically uncharacteristic. The essence of drawing causal inferences about effective schools starts with being able to compare schools that serve similar students but get different results, whereas David chose a school district for his case study that can’t be matched with anything else. Given his choice of target, he would never have been able to convince a skeptic that it is the education system of Union City rather than its unique demographics that is responsible for students beating the odds. And it isn’t just that it is a Hispanic city that make Union City problematic in terms of drawing comparisons, but the question of what leads Hispanics to locate there rather than in one of the many adjacent communities that are more racially/ethnically heterogeneous. Maybe the Hispanics who are drawn to Union City are different in terms of their values, including their expectations for their children’s education. There is no way to tease apart the comingled effects of schooling, community, and family in this case. It is a mess from the perspective of causal reasoning.

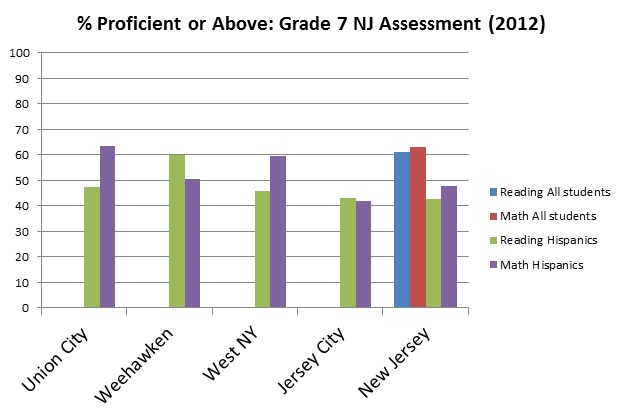

But wait, there’s more! The Union City schools aren’t actually stellar – they’re just average to somewhat above average depending on the outcome being examined. The figure below presents 7th grade state assessment results in math and reading for Hispanics in Union City, three abutting school districts, and the state as a whole.[i] I focus on Hispanics because the vast majority of the students in Union City fall into this demographic category. Thus contrasting the performance of Hispanic students in Union City with Hispanic students in other districts provides more of an apples-to-apples comparison than if Union City and other districts were compared based on the performance of all of their students.

As the figure illustrates, Union City and West New York have about 60% of their Hispanic students performing at the proficient level or above in math, which is roughly the state average for all students. These two districts do a better job in math for Hispanics than Weehawken and Jersey City. On reading, in contrast, Hispanics in Weehawken do the best, performing at the state average for all students, whereas those in Union City perform at roughly the same level as those in West New York and Jersey City, far below the state average for all students.

The comparative performance of Union City does not display the striking exceptionality that my colleague Matt Chingos and I have found in studies of district exceptionality in North Carolina and Florida. This is suggested by the above figure. It is clear when the school districts in New Jersey are ranked in terms of the performance of the Hispanic students on state assessments. In reading Union City is ranked 140th out of 266 districts[ii] in New Jersey in the performance of Hispanics at 7th grade. In mathematics, it does better, ranking 69th among districts in the state in the performance of Hispanics.[iii]

Are we really supposed to expect dramatic changes in American public education from a playbook based on the practices of a district that is middling in teaching reading and doesn’t crack the top quartile in teaching math? Is a district that only manages to bring its students up to the state average of proficiency to be our exemplar, particularly when the state standard is relatively low?

Memo to those who want to study the distinctive characteristics of high flying districts:

First, pick high flying districts. State databases and statistics are essential to this task. Reformers might be motivated to replicate the practices of the very best districts whereas no one is going to be energized by the possibility of adopting practices that merely result in being average.

Second, compare the practices of districts with similar students but different outcomes. We need to know how high flying districts are different from less effective ones, which can only be derived from comparisons. In the words of Rudyard Kipling, “What can he know of England who only England knows?” What seems an important practice when examined in isolation may look quite different if it turns out that less successful districts are doing exactly the same thing.

Third, compare practices among high performing districts with similar students. There are probably several approaches to creating effective schools. We’ll never know that if we only focus on the practices of one exemplar.

Fourth, identify distinctive and successful practices at an operational and actionable level. Of course, successful organizations that deliver human services are staffed with people who can do their jobs and share the objectives of the organization. How, in particular, do these organizations attract or develop good staff and secure their commitment?

Once we have valid descriptions of the distinctive operational differences between good and not-so-good schools, controlling for differences in student background and out-of-school factors that are beyond district control, the social science of district reform can move to planned and carefully evaluated interventions. That is our playbook. That is where we need to be. I don’t think the path goes through Union City.

[i] My selection of 7th grade assessment results is arbitrary. The story doesn’t change much if other grades are the focus.

[ii] These are districts in which enough Hispanics took the examination for the state to report a score for this group.

[iii] Comparing districts based only on the achievement test scores of Hispanic students in one grade is a rough and ready approach. A thorough and sophisticated effort would use student-level data and look at outcomes across multiple grades, examine changes over time, and employ controls for family background, state trends, and the multi-level nature of the data. Union City’s performance might well look different when seen through such a lens, which I hope someone will have the time, data, and resources to bring to bear.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).