This report is part of the Series on Financial Markets and Regulation and was produced by the Brookings Center on Regulation and Markets.

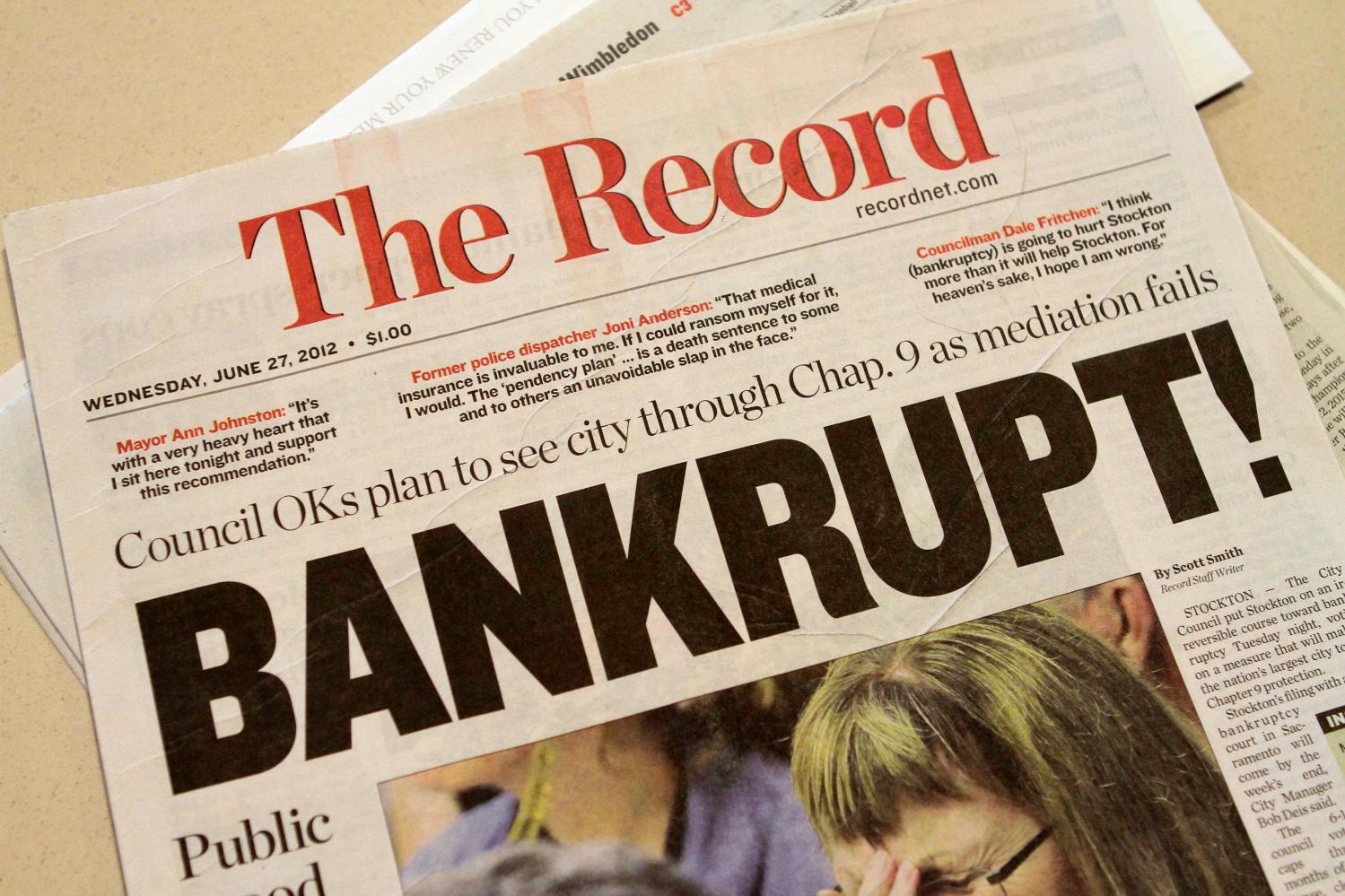

Less than two months into the coronavirus crisis, and despite the massive infusion of federal funds, a rise in business bankruptcies has already begun. Even if the current efforts by Congress, the Federal Reserve, and Treasury to counteract the economic shutdown are effective, an enormous wave of bankruptcies may come. How effective will the bankruptcy system be as a second line of defense for consumers and businesses that are unable to avoid default?

The good news is that the bankruptcy system ordinarily works well, even in times of crisis. The framework that eventually led to the current Chapter 11—bankruptcy’s reorganization provisions—was forged in the periodic economic “panics” of the late nineteenth century and used to restructure the numerous railroads that defaulted.[1] Although this report focuses primarily on business bankruptcies, note that the nation’s bankruptcy judges also handled roughly 1.5 million consumer bankruptcies a year as recently as the early 2000s.[2]

Based on this track record, it is tempting to simply assume bankruptcy will be available as needed, with no special planning necessary. This would be a mistake. The bankruptcy system has three major limitations of great importance in the current environment: it has proven much more effective at reorganizing large corporations than small and medium-sized businesses; it functions very differently when the bankruptcy courts are congested; and Chapter 11 depends on the debtor having financing during the bankruptcy case. It is essential that the Federal Reserve and Treasury anticipate these limitations and consider creative solutions to the problems that are likely to arise.

After briefly describing the reasons to expect a wave of bankruptcies and the key limitations of Chapter 11, this report considers proposals to impose a bankruptcy-like standstill and offers several strategies for adapting the bankruptcy process for the current crisis, concluding with a brief comment on the capacity of the bankruptcy system.[3]

The author did not receive financial support from any firm or person for this article or from any firm or person with a financial or political interest in this article. He is currently not an officer, director, or board member of any organization with an interest in this article.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).