Content from the Brookings Institution India Center is now archived. After seven years of an impactful partnership, as of September 11, 2020, Brookings India is now the Centre for Social and Economic Progress, an independent public policy institution based in India.

Using three cities—Ajmer, Allahabad, and Visakhapatnam—as examples, our latest study, “Building Smart Cities in India: Allahabad, Ajmer and Visakhapatnam” highlights governance challenges, infrastructure gaps, institutional arrangements, and financial tools that policymakers must consider to reach their local ambitions.

It highlights the key economic distinctions among Ajmer, Allahabad, and Visakhapatnam, illustrating the potential areas in which Smart City improvements could be targeted for future action.

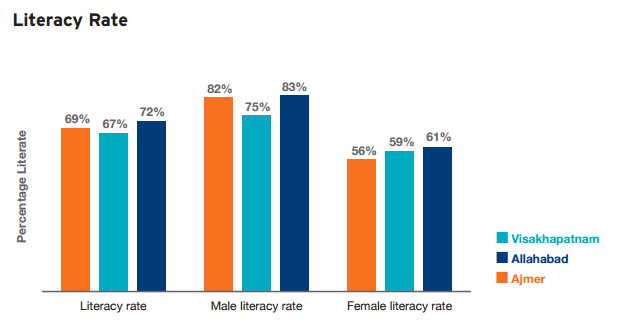

The literacy rate, for example, is an important determinant of prosperity, as it affects regional workforce capabilities and industrial patterns of development. The overall literacy rates of Ajmer, Allahabad, and Visakhapatnam is very similar. However, equitable outcomes can still vary, with Allahabad, in particular reporting a narrower gender literacy gap.

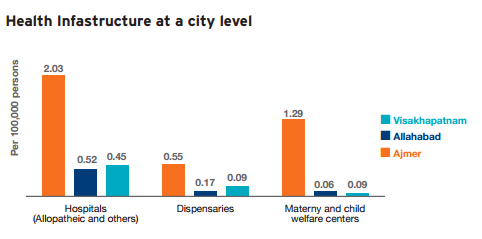

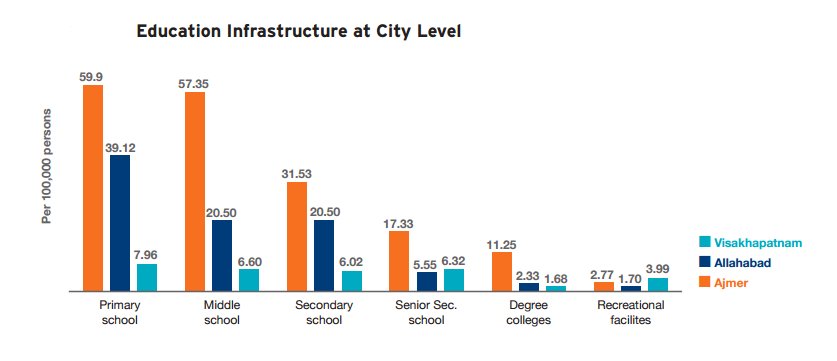

The state of each city’s education and health infrastructure is similarly important to examine. Ajmer consistently outperforms Allahabad and Visakhapatnam on this indicator. Allahabad, meanwhile, frequently lags behind in each category, perhaps in part explaining its higher infant mortality rate. Although Visakhapatnam contains more health facilities overall given its large population, it tends to rank lower on a per capita basis in many categories.

Ajmer is once again a frontrunner as far as educational amenities are concerned. It boasts a higher concentration of primary and secondary schools and colleges, in line with its generally higher literacy rates. Visakhapatnam, interestingly, tends to have a higher share of recreational facilities by comparison. Collectively, such variation helps explain the foundational infrastructure already in place—or lacking—in these cities as they accelerate various improvements over time.

The availability of local government public services, as described below, can shed light on how much progress each city has made toward greater modernisation.

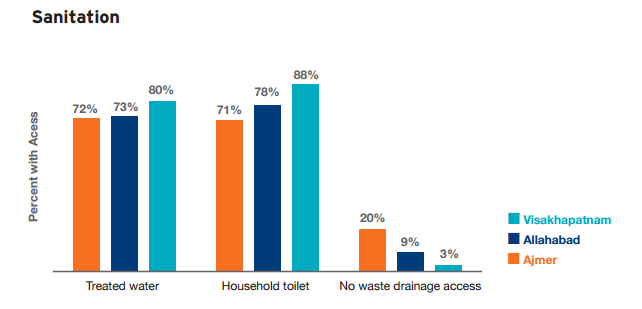

Sanitation and telecommunications infrastructure—the latter of which provides essential digital connectivity—are two such public services.

Visakhapatnam has more widespread access to treated water, in-house toilets, and wastewater drainage, while Ajmer struggles to provide these basic services despite having a smaller population—possibly indicating its more limited administrative capacity.

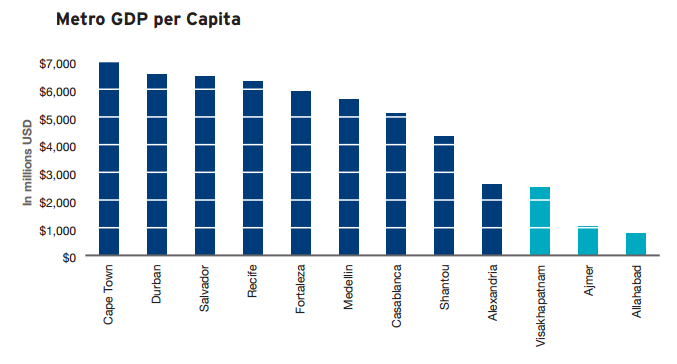

However, even among relatively poor metro areas across the world, the Indian metro areas stand out. The GDP per capita in Ajmer and Allahabad is easily the lowest, hovering near $1,000.

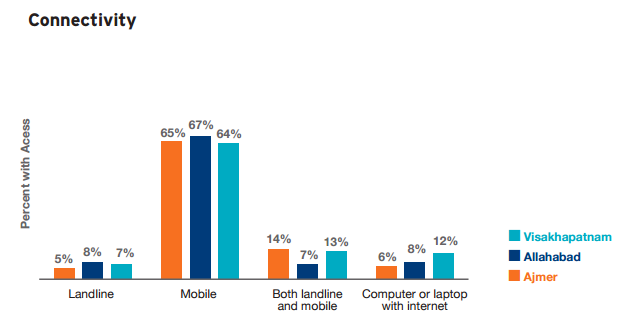

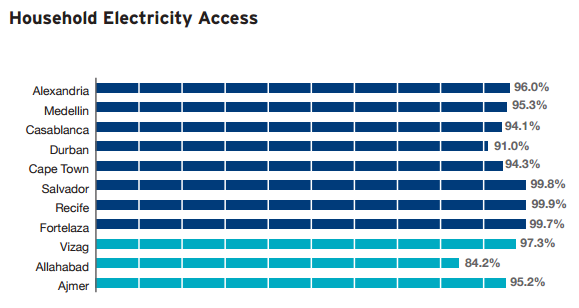

Electricity is equally important to economic development, and it is a key requirement to operate Smart City technologies. It is simply impossible to operate digital infrastructure without electricity. The Indian cities trail their Brazilian peers, but Visakhapatnam and Ajmer both exceed Medellín, Casablanca, Cape Town, and Durban. However, Allahabad has easily the lowest electricity access of all cities. The inability to charge a laptop or connect to the Internet from Indian homes presents a serious barrier to any Smart City project that requires direct individual interaction.

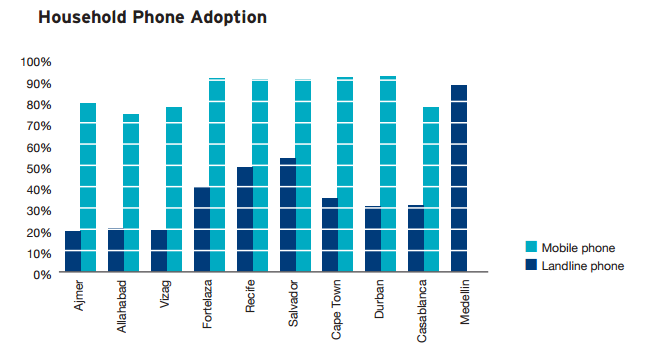

The Indian cities also lag behind on mobile phone adoption—70–80 percent adoption rates compared with 90 percent in Brazilian and South African cities. Smartphones are a particularly important component of Smart City projects, allowing mobile access to web services such as transit arrivals, utility usage monitoring, and mobile financial transactions.

Considering the expected growth in India’s urban population, the launch of the Smart Cities Mission offers an overarching opportunity and underscores India’s urban challenges. The opportunity lies in using digital technologies in each of the proposed Smart Cities to improve growth trajectories, both in terms of quality of life and economic output. The challenge is confronting the significant hurdles to achieving such growth.

As the Smart City Mission continues to develop, it is critical that cities and their federalist peers deliver on these clear needs.

Download the PDF of the report, “Building Smart Cities in India”

VIDEO | Amitabh Kant launching the report

VIDEO | Presentation

VIDEO | Panel discussion

VIDEO | Adie Tomer | Lessons from developed economies

VIDEO | Elizabeth Kneebone | How urbanisation differs

Read Also

Blog | Installing digital technologies alone will not deliver results

Commentary | Municipal bond market could be the answer to financing woes of Smart Cities: The Wire

Citation | Huge gap between power supply and mobile phone penetration: Financial Express

Citation| Water, toilets, phones: Smart-city picks trail global peers on all fronts: Hindustan Times

Blog | India should look toward its global peers to drive smart city improvements

Blog | For smart cities to succeed, strengthening local governance is a must: The Wire

Blog | A governance-first approach to India’s smart cities

Blog | Chennai floods: A Smart City must also be a resilient city: Times of India

Commentary | Uniqueness of India’s smart cities: Mint

Op-ed | Delivering on the promise of India’s smart cities

Report | Getting smarter about smart cities

Event Podcast | Former MoUD Minister of State Babul Supriyo speaking at our Roundtable

Event Report | Smart Cities roundtable defines critical areas of interest