Bipartisanship has reappeared in health care reform. The three major committees with jurisdiction over Medicare policy have come together around a bipartisan, bicameral framework to change the way the Medicare program pays physicians. The reforms move Medicare’s reimbursement of physicians away from fee-for-service, which pays doctors based on the number and intensity of services they provide, toward paying them for producing better care, keeping patients healthy, and lowering overall costs. We’ve described these reforms in Medicare’s sustainable growth rate (SGR) payment system previously.

But one critical obstacle to enactment remains: Congress must come up with a way to pay for the legislation, which will likely cost around $130 billion to as much as $170 billion. The vast majority of this additional spending would be needed to offset the scheduled payment cuts under the existing SGR formula, which reduces physician payment rates automatically when physician-related Medicare spending exceeds the growth rate of the economy. While the SGR system had a laudable cost-control goal, relying on across-the-board payment cuts has not worked out as planned in practice. Congress has passed short-term patches to delay the cuts in every year since 2002, and the gap between actual Medicare spending and the SGR target spending is now so large that a 24 percent cut in physician payment rates would be required when the latest patch runs out. That deadline is looming again on April 1, so progress on “pay-fors” is needed soon to avoid another patch.

Here, we describe the key costs in the physician payment reform legislation. We then describe ways to pay for these costs that could provide an effective policy and political path forward. From a policy standpoint, our proposals share the goal of the legislation to promote better care and avoid payment rate cuts. It would be ironic to fund the physician payment reforms intended to move away from fee-for-service payments for physicians simply by cutting payment rates for other health care providers in Medicare.

From a political standpoint, our proposals reinforce the bipartisan goal of better care in Medicare, and they are based on proposals that have had some bipartisan support in the past. Even so, $130 to $170 billion is a big hurdle. Consequently, we also outline a “semi-permanent” physician payment fix as an alternative to yet another short-term SGR patch if bipartisan agreement on how to pay for the costs of the permanent legislation is not possible.

The Costs of Physician Payment Reform Legislation

The legislation gives physicians an annual payment rate update of 0.5 percent from 2014 to 2018, after which payment rates would be held flat through 2023. Based on previous estimates, this component of the legislation will likely cost more than $125 billion over 10 years. This is much more than the short-term SGR “patches” that Congress has cobbled together over the years largely by squeezing payment rates of other health care providers.

But the legislation is about more than just stabilizing physician payments. Physician payment reform will improve care only if it is accompanied by adequate support for physicians to implement meaningful changes in care to improve quality and lower costs. The proposed legislation includes bonuses for physicians who shift to alternative payment models like medical homes, case-based payments, or accountable-care payments. Such subsidies would help physicians pay for the up-front costs of necessary practice changes – for example, adding staff to help coordinate care, implementing effective information systems, and working out care coordination arrangements with other providers.

The Congressional Budget Office estimated the five-year cost of these bonuses at about $5 billion in the earlier Senate Finance Committee bill. This may not be enough to support significant investments in reforming: annual Medicare physician spending totals about $75 billion now, or over $400 billion over five years. As the legislation is finalized, Congress should consider providing opportunities for larger bonuses in return for higher expectations about practice reforms that can improve care and reduce costs. The legislation also includes $200 million to assist smaller physician practices implement reforms.

In addition, the legislation includes needed funding for developing better measures of the quality and cost of care. It should include provisions for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to improve its systems to share data with health care providers – in compliance with appropriate beneficiary privacy protections — to help them improve care under the alternative payment arrangements. While critically important, these costs would total less than $1 billion. The legislation takes further steps to enable organizations to obtain Medicare data to assist providers with improving care and to enhance the availability of performance measures.

Included in previous physician payment reform proposals but not yet in this one are provisions that address other problems in Medicare payments – e.g, relaxing limits on outpatient therapy services. These provisions are likely to be added later, as they will help balance objections of other provider groups that will be affected by the pay-fors for the physician legislation. In the previous Senate Finance Committee draft, the additional provisions cost around $40 billion. As these provisions are added, it could also be an opportunity to reinforce steps to improve care, such as creating complementary incentives for hospitals and post-acute providers to work with physician practices to improve care.

Paying for the SGR Fix Through Medicare Reforms That Reinforce the Goals of Physician Payment Reform

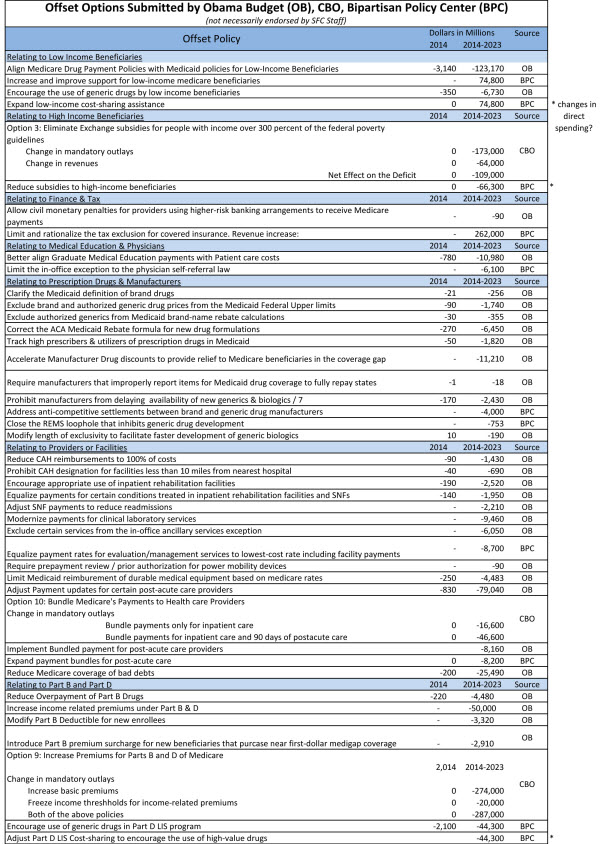

The Congressional committees have floated a list of potential sources of savings to pay for these reforms, reproduced below.

The list is helpful in starting discussion, but there is a bigger opportunity. If Congress can come up with off-sets for physician payment reform that support improvements in care as well as lower costs, the whole package could have a more meaningful effect on beneficiary care than the physician payment reforms alone. This could assure beneficiaries and other health care providers that these savings are not just payment cuts that must be absorbed, but steps to help reduce spending through reforms that improve care.

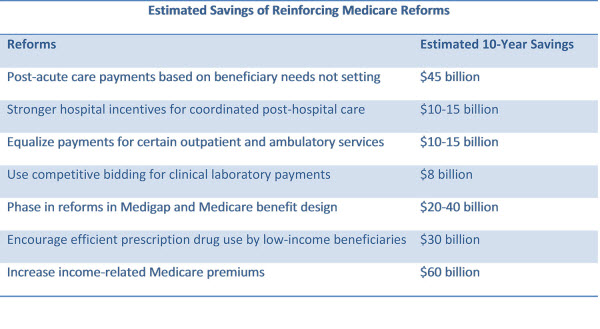

With this goal in mind, here is our suggested list of ways to pay for physician payment reform by reinforcing the goal of better care at a lower cost in Medicare. The “reinforcing reforms” are summarized in the Table below.

Reinforcing Payment Reforms for Post-Acute Care, Hospitals, and Other Medicare Providers

Reform payments for post-acute care, so that payments are based on a beneficiary’s health status and care needs rather than the type of facility that provides that care. Medicare often pays very different amounts for care after the hospital, based not on the beneficiary’s need but on whether they receive care in an inpatient rehabilitation facility, a nursing home, or in their own home. Substantial evidence suggests that this approach is inefficient, and that many beneficiaries could get the care they need in less intensive and more convenient settings.

It would take a few years to put in place a system that pays post-acute providers a rate that is based on an assessment of a patient’s needs, but the foundational work for such payment systems has been developed in collaboration with post-acute care providers. Congress could begin this reform now, with resulting savings on the order of $45 billion dollars over the next 10 years.

Strengthen the hospital incentive payment for coordinated post-hospital care. Readmissions resulting from complications after hospital discharge are costly and can sometimes be avoided when patients receive proper, well-coordinated follow-up care. Nearly one in every five Medicare patients is readmitted to the hospital within 30 days of their initial hospital discharge. While this is a multibillion-dollar cost, it is lower than in the past, at least in part because the Affordable Care Act included a penalty for hospitals with excessive readmission rates. The penalty for an unusually high readmission is currently 1 percent, increasing to 3 percent over the next several years.

Building on this reform, hospitals could share in the savings from reducing readmissions and working with more efficient post-acute care providers, and they could bear more of the costs when they fail to do so. In exchange for a moderate increase in base Medicare hospital rates, hospitals should assume greater responsibility for the costs of any readmission that occurs within 90 days, and (in conjunction with our previous proposed reform) could also assume some financial responsibility for unusually costly or low-quality post-acute care. The resulting incentives to make sure the patient receives proper follow-up care could save about $10-15 billion; this represents a more promising alternative for hospitals than just cutting their payment rates.

Pay for outpatient care based on services provided, not the type of facility. Opportunities analogous to “site-independent” reforms in post-acute payment exist for other Medicare services. In particular, Medicare pays a substantially higher rate for some services provided in a hospital outpatient department than for the same services provided in a doctor’s office or other ambulatory care setting, even though the services can be provided safely in the latter settings. The resulting higher payment for such physician services when a physician practice is part of a hospital is at odds with the goal of supporting physicians in improving care while lowering costs in their offices. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MEDPAC) has suggested that reasonable steps toward equalizing hospital outpatient and physician office payments could save around $10-15 billion over ten years.

Use competitive bidding to set payments and improve quality for Medicare services, starting with lab tests. Medicare’s method for reimbursing many services besides physician care is based on detailed fee schedules that are hard to keep up to date, as costs of the services or products go down and as new ones are introduced. This is particularly true for laboratory tests, where technological improvements in many routine tests have brought down the costs of both individual tests and batteries of tests. The HHS Office of Inspector General found that, as a result of these improvements in technology, Medicare was overpaying for clinical laboratory tests in the range of $900 million a year.

Instead of trying to keep payments up to date by regulation, Medicare could begin using a competitive bidding approach for basic lab tests and expand the program over time. This more flexible approach to lab payment might also better encourage new kinds of tests, such as personalized medicine tests, that do not have good precedents in existing laboratory services and thus may not receive payments that reflect their value. Medicare has begun paying for some “durable medical equipment” products through competitive bidding, with substantial savings. A reasonable estimate of the savings resulting from using competitive bidding for laboratory tests is about $8 billion over ten years.

Reinforcing Benefit Reforms

Medicare was created to provide access to quality care and financial security for beneficiaries. Yet Medicare’s benefit structure for Part A (mainly hospital) and Part B (mainly physician and outpatient) services has not changed significantly since the 1960s, resulting in poor protection against high costs and little support for beneficiaries to get better, less-costly care. There is no out-of-pocket limit on a beneficiary’s out of pocket costs. As a result, as health care costs have risen, beneficiaries are increasingly exposed to substantial financial risk if they have a serious illness. Medicare beneficiaries must currently pay up to $1,216 out of pocket for a hospital visit before the Medicare program begins paying a portion of the hospital bill. And there is a separate deductible for physician services of $147, in addition to unlimited copayments of 20 percent or more.

Medicare’s existing benefit structure also prevents beneficiaries from saving money when they choose high-quality, low-cost care. Some Medicare services have no copayments at all; others have large copayments. The potential for high and unpredictable out-of-pocket costs has driven beneficiaries to purchase private supplemental insurance (“Medigap”) to protect themselves financially. According to CBO, about 85 percent of beneficiaries in Medicare’s fee-for-service program have supplemental coverage that insulates them to varying degrees, sometimes completely, from out-of-pocket expenses. Indeed, many of the standard Medigap plans pay for the full out-of-pocket cost of Medicare services, regardless of their quality or efficiency. These plans are also expensive – premiums can be much higher than beneficiaries’ Medicare premiums.

Medicare benefit reforms could give beneficiaries better protection against high expenses, reduce their total out-of-pocket payments, and reduce overall Medicare spending at the same time. The spending reductions would result from beneficiaries having the opportunity to share in the savings when they get better care at a lower cost, aligning with the physician payment reforms. The details have been described in reports from Brookings, the Bipartisan Policy Center (BPC), MEDPAC, and many other groups. Here are the major proposals:

Reform Medicare supplemental insurance (Medigap) to eliminate first-dollar coverage. Supplemental Medigap coverage that eliminates all Medicare cost sharing (say, below 10 percent up to an out-of-pocket limit) could be prohibited, or alternatively, beneficiaries who choose such coverage could pay a fee that reflects the impact of their “first-dollar” coverage on overall Medicare costs. If implemented immediately, this reform could save over $50 billion or more over 10 years, though we recommend phasing it in.

This reform would also significantly reduce Medigap premiums paid by the average beneficiary by more than their out-of-pocket payments would increase. Thus, it would lower the overall amount the average beneficiary pays for health care and continue to protect beneficiaries against high out-of-pocket costs.

Create a single deductible and an out-of-pocket limit for hospital and ambulatory services (Part A and Part B) and reform Medicare copayments. Like all other modern insurance, Medicare should have a single deductible for hospital and physician services and a limit on individuals’ total out of pocket expenses. This reform would also implement reasonable copayments where they don’t exist and reduce those that are excessive. Beneficiaries would be protected from excessive costs through the limit on the total out-of-pocket costs that we have already described. To avoid exposing beneficiaries to excessive costs that may stop people from seeking care when needed, the reform could exempt certain services, such as preventive services, from copayments and deductibles, and could provide extra protections for low-income beneficiaries. Taken together, these reforms could save about $50 billion if implemented immediately, though we recommend phasing in the reforms.

Implement these Medigap and benefit reforms together. These reforms would reinforce each other. For example, an out-of-pocket limit and copayment reforms in Medicare’s benefit package would enable the reforms in Medigap to have a greater impact, reducing Medicare costs and Medigap premiums further while still giving beneficiaries better protection against high costs. Implementing these reforms together would result in over $110 billion in total savings over 10 years if done now.

Phase in the benefit reforms. Proposals like changing Medicare copayments and restricting supplementary insurance have long been proposed yet never enacted. Millions of elderly and disabled Americans have already purchased supplemental insurance to limit any financial risk resulting from high medical bills, or receive supplemental coverage as a valuable retirement benefit. While the deductible and copay reforms would reduce costs for beneficiaries on average, as well as protect against high expenditures, a large number of beneficiaries with low to moderate medical expenses would pay somewhat more.

To limit such disruptions, the benefit reforms could be phased in over time. One approach would be to start modestly, such as by introducing a premium surcharge for beneficiaries with the most generous Medigap plans as President Obama has proposed, or by gradually adjusting deductibles and copayments over the next decade. The changes could be paired with copayment reductions for some valuable services as well as with the opportunities for beneficiaries to save when choosing high-quality, low-cost providers.

Another approach, which would be complex to implement, would be to apply all the reforms to new Medicare beneficiaries starting about five years from now. Official savings estimates for such options aren’t yet available, but we estimate this could save on the order of $20 to $40 billion over ten years, depending on the pace of the transition. While these steps may be politically challenging, the improvements in access to quality, innovative care coming with the physician payment reforms create a unique opportunity to adopt them.

Pilot a mechanism for Medicare providers to share savings with beneficiaries. To enable even greater beneficiary savings, and to support more meaningful engagement of Medicare beneficiaries in health care reforms, Medicare should also pilot ways to enable beneficiaries to share in the cost savings when they choose physician groups, hospitals, post-acute providers, or accountable care organizations that have lower overall Medicare costs while meeting quality standards. For example, beneficiaries who affirmatively opt in to a lower-cost, high-quality ACO or who choose lower-cost, high-quality providers for procedures or for managing their chronic conditions could receive a subsidy on their premiums or copays.

Create incentives for more efficient prescription drug use by beneficiaries dually eligible for both Medicaid and Medicare. Under the current Medicare program for prescription drug coverage, these beneficiaries receive additional subsidies that reduce the amount they have to pay for their prescriptions, especially for brand-name drugs. This additional assistance means Medicaid beneficiaries save very little when they choose available lower-cost but equally effective drugs, making it more difficult for drug plans to encourage the use of such drugs. Introducing modest increases in copayments for brand-name drugs for those receiving low-income subsidies would help encourage more efficient prescription drug use without reducing quality of care. This reform could save as much as $30 billion over ten years.

Raise the Medicare premium for higher-income individuals: Medicare already adjusts the premiums beneficiaries pay depending on their income; individuals with incomes over $85,000 for a single person and $170,000 for a couple pay higher premiums than other seniors. Many bipartisan Medicare reform proposals have included additional means testing as a way to reduce Medicare spending. While this reform might be viewed as primarily shifting Medicare costs from taxpayers to higher-income beneficiaries, it too could be phased in over time and eventually paired with reforms that enable beneficiaries to lower their payments when they use less-costly, high-quality care. An income-related premium along the lines of the President’s 2014 Budget proposal could save almost $60 billion over ten years.

A Semi-Permanent SGR Fix

If agreement cannot be reached on how to offset the full cost of permanently repealing the SGR, Congress will likely turn again to passing a lower cost, short-term physician payment fix, with the hope that the stronger bipartisan foundation for reform will make it easier to do the next time around.

However, the strong agreement on the changes in physician payment that should accompany any permanent SGR fix creates a new alternative to just “kicking the can” yet again. In particular, Congress could enact the structural changes in Medicare’s physician payment system, including the revised approaches to tying payments to quality measures, the opportunity for physicians to shift to alternative payment systems with bonuses for doing so, and the supporting improvements in data and quality measures. Of course, this could not be done in conjunction with just a short-term patch in the physician payment rates; if health professionals and Congress have to return to this issue again within the next few years, it will be very difficult for them to focus attention on actually implementing meaningful reforms in care. Physicians need more substantial stability in their payment systems to make the needed investments in improving care; that is a main reason why the short-term patches are so detrimental to physician leadership in health care reform.

A permanent fix would be better, but a five-year, semi-permanent fix would give physicians far more predictability than they have had over the past decade. Thereafter, if short-term patches were again needed, they would at least occur on top of a payment system that is much better able to support physicians in implementing badly needed reforms in care. Moreover, the experience accumulated with the alternative ways of paying physicians might also provide a basis for beneficial adjustments or course corrections in Medicare’s physician payments and other provider payment systems.

According to CBO’s latest estimates, a five-year period of physician payment stability would cost $50-60 billion; the additional structural reforms needed to support physicians in reforming care would add another $10 billion. The much lower cost of a five-year fix would make devising a corresponding package of offsets that improves the value of care for Medicare beneficiaries and receives bipartisan support a simpler task, though still a daunting one.

Time for Reform

The unprecedented progress in Congress toward reforming Medicare’s physician payment system holds out real hope that Medicare can become a support rather than a recurring obstacle to physician leadership in improving American health care. The biggest remaining obstacle to this advance is how to pay for it. Through the reinforcing Medicare reforms that we have described here, as well as possible consideration of a semi-permanent version of the “SGR fix,” meaningful Medicare physician payment reform may be closer than ever.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edPaying For A Permanent, Or Semi-Permanent, Medicare Physician Payment Fix

February 14, 2014