Convincing Americans that they should worry about the federal deficit and debt is tough, despite all those warnings about the inevitable crisis.

The federal debt, the sum total of all the government’s past borrowing, is huge by historical standards: bigger as a share of the economy than at any time in U.S. history except for World War II. Yet the U.S. Treasury still is able to borrow billions every day at very low interest rates. Investors demand less than 2% to lend to the Treasury for 10 years.

But the trajectory of the debt is worrisome for one inescapable reason: When you owe a lot of money and interest rates rise, your interest tab mounts.

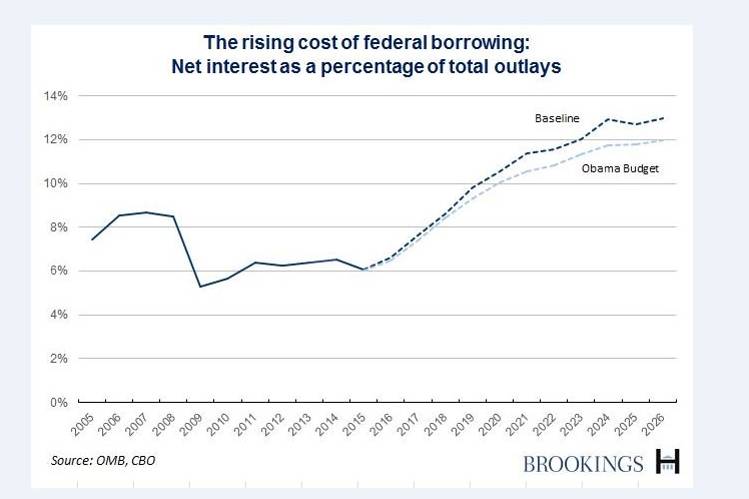

Today, interest consumes a bit more than 6% of all federal outlays. But the latest Congressional Budget Office baseline projections suggest that, without new tax or spending legislation, interest will account for more than 13% of all federal outlays in 2026. That’s partly because interest rates are expected to rise from today’s very low levels; CBO expects the average yield on 10-year Treasury notes, now around 1.9%, to climb to 4.1% over the next decade. There will also be more debt on which to pay interest because the government will be borrowing each year to cover the deficit.

Of course, Congress and the president–Barack Obama or his successor–could raise taxes or cut spending. That would mean less debt and thus lower interest payments. But the latest CBO scoring of President Obama’s budget suggests that even if Congress accepts each of his tax and spending proposals, interest in 2026 still would account for 12% of federal spending.

That’s a lot of money–more than the White House projects for annually appropriated spending in 2026 by all government agencies combined outside of the Pentagon.

Of course, 10-year projections can be wrong. Interest rates could be higher or lower than CBO expects. Congress could spend more or less than expected on annual appropriations. But there remains one inexorable fiscal fact: When you owe a lot of money and interest rates climb, you’ll be spending a lot more on interest.

Editor’s note: This piece originally appeared on The Wall Street Journal’s Washington Wire.

Commentary

Op-edIn CBO’s projections, a growing reason to worry about the federal debt

March 30, 2016