Security

Next generation technologies are increasingly available almost as quickly as they are developed. How can these advanced technologies be deployed responsibly by democratic states? How will rogue regimes and non-state actors look to exploit them and how can democratic governments cooperate in countering their malicious use? How can democratic societies navigate threats from authoritarian adversaries in the information domain and build resilience to cyber threats?

Autonomous Weapons and Advanced Military Technology

Artificial intelligence and emerging technologies have a wide range of possible military applications and the potential to transform weapons systems. Although lethal autonomous weapons systems have gained widespread attention, the policy questions posed by advanced technologies extend well beyond just how to regulate “killer robots.” How will advanced military technologies reshape conflict and strategic stability in the years and decades to come? How can democratic countries best manage the risks they introduce?

-

BookInformation War

BookInformation WarThe struggle to control information will be at the heart of a U.S.-China military competition.

Authors

-

TechStreamUnderstanding the errors introduced by military AI applications

TechStreamUnderstanding the errors introduced by military AI applicationsThe embrace of AI in military applications comes with immense risk: New systems introduce the possibility of new types of error, and understanding how autonomous machines will fail is important when crafting policy for buying and overseeing this new generation of autonomous weapons.

Authors

-

ReportMilitary innovation and technological change: Preparing for the next generation of cyber threats

ReportMilitary innovation and technological change: Preparing for the next generation of cyber threatsTechnological change of relevance to military innovation may be faster and more consequential in the next 20 years than it has proven over the last 20 — and this sense of possibility is being driven mostly in the cyber realm.

Authors

-

TechStreamApplying arms-control frameworks to autonomous weapons

TechStreamApplying arms-control frameworks to autonomous weaponsExisting arms-control regimes may offer a model for how to govern autonomous weapons, and it is essential that the international community promptly addresses a critical question: Should we be more afraid of killer robots run amok or the insecurity of giving them up?

Authors

-

Blog“War is interested in you”: Balancing the promise and peril of high-tech deterrence

Blog“War is interested in you”: Balancing the promise and peril of high-tech deterrenceTo the extent that the U.S. does not adequately account for how its own approach to integrating advanced technologies into deterrent strategies can cause misperception, instability, and miscalculation, it does not minimize opportunity for great power war — it creates it, Melanie W. Sisson argues.

Authors

-

EventRussia, China, and the future of strategic stability

EventRussia, China, and the future of strategic stabilityOn November 17, Brookings will host an event to discuss emerging technologies, modernization efforts in China, Russia, and the U.S., the implications of this for the future of strategic stability, and how these developments should inform U.S. policy going forward.

Information

-

EventA national strategy for AI innovation

EventA national strategy for AI innovationOn May 17, the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence (NSCAI) Chair Dr. Eric Schmidt, Commissioner Gilman Louie, and Commissioner Mignon Clyburn together with Sen. Joni Ernst, ranking member of the Senate Armed Services Subcommittee on Emerging Threats and Capabilities, discussed NSCAI’s final report and policy options to substantially boost investment in AI innovation and protect American interests.

Information

-

EventThe art of war in an age of peace

EventThe art of war in an age of peaceOn June 15, Foreign Policy at Brookings hosted an event to discuss Michael O'Hanlon's new book, “The Art of War in an Age of Peace: U.S. Grand Strategy and Resolute Restraint,” featuring former Under Secretary of Defense for Policy Michèle Flournoy.

Information

-

EventThe Marine Corps and the future of warfare

EventThe Marine Corps and the future of warfareThe Marine Corps is pursuing significant changes to address the realities of great power competition, including implementing a new force design.

Information

-

TechStreamLoitering munitions preview the autonomous future of warfare

TechStreamLoitering munitions preview the autonomous future of warfareLoitering munitions represent a bridge between today’s precision-guided weapons that rely on greater levels of human control and our future of autonomous weapons with increasingly little human intervention.

Authors

Cybersecurity

As individuals, organizations, and governments around the world have grown more dependent on digital information and services, they have also become more vulnerable to cyberattacks and intrusions. How can policymakers build resilience to this evolving threat? Should ransomware payments be banned?

-

TechTankProtecting national security, cybersecurity, and privacy while ensuring competition

TechTankProtecting national security, cybersecurity, and privacy while ensuring competitionThe U.S. government has in the past been able to address concerns with monopoly power, including breaking up firms that have abused their dominant positions, without sacrificing other values we hold dear, Stephanie Pell and Bill Baer write.

Authors

-

TechStreamThe urgent need to stand up a cybersecurity review board

TechStreamThe urgent need to stand up a cybersecurity review boardAmid widespread computer vulnerabilities, getting a cyber incident review board up and running should be a serious priority, one that has the potential to seriously improve the disastrous state of cybersecurity.

-

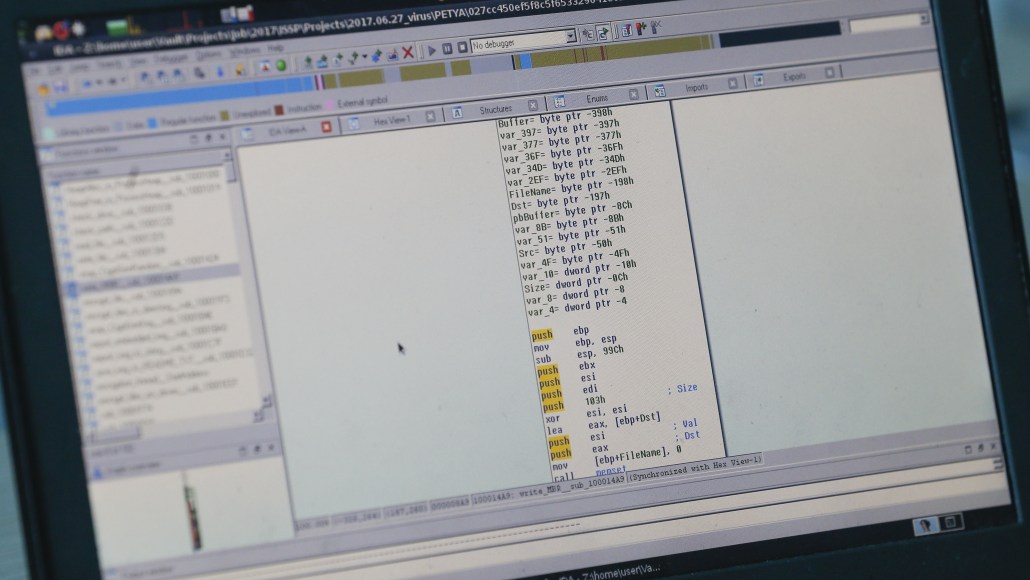

TechStreamHow the NotPetya attack is reshaping cyber insurance

TechStreamHow the NotPetya attack is reshaping cyber insuranceThe dispute over how to assess insurance claims from the NotPetya attacks threatens to remake the insurance landscape.

Authors

-

BlogProtecting the cybersecurity of America’s networks

BlogProtecting the cybersecurity of America’s networksTo Build Back Better, Biden’s FCC must secure U.S. broadband networks and reverse Trump-era cybersecurity unbuilding, says Tom Wheeler.

Authors

-

BlogAfter the SolarWinds hack, the Biden administration must address Russian cybersecurity threats

BlogAfter the SolarWinds hack, the Biden administration must address Russian cybersecurity threatsCaitlin Chin contrasts the Biden and Trump administration approaches to cybersecurity issues in the wake of the massive SolarWinds hack.

Authors

-

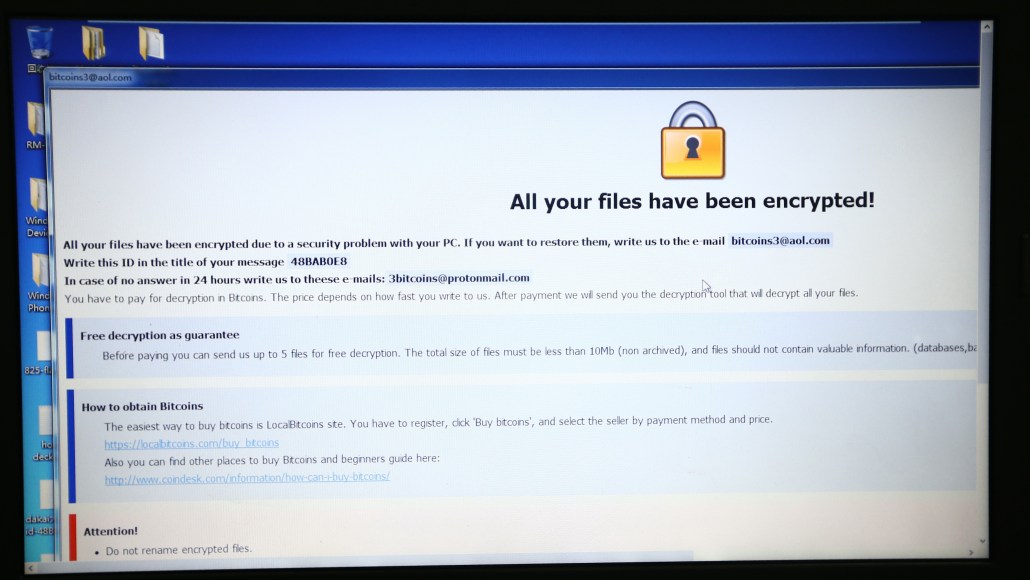

TechStreamShould ransomware payments be banned?

TechStreamShould ransomware payments be banned?At the heart of the ransomware phenomenon is a misalignment of economic and policy incentives that allow criminals to operate successfully and with impunity. Since addressing the problem most often falls to its victims, many have paid up to mitigate damage. There are growing calls for businesses to be banned from paying ransoms. But these calls outright fail to capture what is an enormously complicated policy issue.

Authors

-

TechStreamHacked drones and busted logistics are the cyber future of warfare

TechStreamHacked drones and busted logistics are the cyber future of warfareOur military systems are vulnerable. We need to face that reality by halting the purchase of insecure weapons and support systems and by incorporating the realities of offensive cyberattacks into our military planning.

Authors

-

TechStreamHow African states can tackle state-backed cyber threats

TechStreamHow African states can tackle state-backed cyber threatsThough few African states can compete with the world’s major cyber powers, the region is not inherently more susceptible to state-sponsored cyber threats. Like other regions, Africa faces its own series of opportunities and challenges in the cyber domain. For now, low levels of digitization limit the exposure of many countries in comparison to the world’s more connected, technology-dependent regions. As internet-penetration rates increase, African states can draw on established good practices, international partnerships, and regional cooperation to identify, prevent, and respond to state-sponsored cyber espionage or sabotage of critical infrastructure.

-

TechStreamThe danger in calling the SolarWinds breach an ‘act of war’

TechStreamThe danger in calling the SolarWinds breach an ‘act of war’Describing the SolarWinds breach as an “act of war” risks leading U.S. policymakers toward the wrong response.

Authors

Information Manipulation

Liberal democracies are engaged in a persistent, asymmetric competition with authoritarian challengers that is playing out in multiple, intersecting domains far from traditional battlefields, and the information space is a critical theater. How can democratic societies navigate authoritarian efforts to weaponize information, exploiting the openness of liberal societies? What efforts can be taken to build resilience to authoritarian information manipulation?

-

TechStreamHow China uses search engines to spread propaganda

TechStreamHow China uses search engines to spread propagandaBeijing has exploited search engine results to disseminate state-backed media that amplify the Chinese Communist Party’s propaganda. As we demonstrate in our recent report, users turning to search engines for information on Xinjiang, the site of the CCP’s egregious human rights abuses of the region’s Uyghur minority, or the origins of the coronavirus pandemic are surprisingly likely to encounter articles on these topics published by Chinese state-media outlets.

Authors

-

ReportWinning the web: How Beijing exploits search results to shape views of Xinjiang and COVID-19

ReportWinning the web: How Beijing exploits search results to shape views of Xinjiang and COVID-19As the war in Ukraine unfolds, Russian propaganda about the conflict has gotten a boost from a friendly source: government officials and state media out of Beijing.

-

TechStreamPopular podcasters spread Russian disinformation about Ukraine biolabs

TechStreamPopular podcasters spread Russian disinformation about Ukraine biolabsThe Kremlin has seized on a fresh piece of disinformation to justify its invasion of Ukraine: that the United States is funding biological weapons there. Popular podcasters in the United States have repeated and promoted it for their own purposes.

-

PodcastTechTank Podcast Episode 40: A conversation with Jessica Brandt and Emerson Brooking on the information wars in the Russian invasion of Ukraine

PodcastTechTank Podcast Episode 40: A conversation with Jessica Brandt and Emerson Brooking on the information wars in the Russian invasion of UkraineSamantha Lai is joined by Jessica Brandt and Emerson Brooking to discuss the roles of technology and disinformation in the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and how social media companies and the American government have responded. They also discuss the precedents being set for the future of the global internet.

Authors

- Samantha Lai

- Jessica Brandt

- Emerson Brooking

-

External PublicationChina’s ‘Wolf Warriors’ Are Having a Field Day With the Russia-Ukraine Crisis

External PublicationChina’s ‘Wolf Warriors’ Are Having a Field Day With the Russia-Ukraine CrisisAs U.S. and European diplomats scramble to try to stave off another Russian invasion of Ukraine, another major player is capitalizing on the crisis to advance its geopolitical interests: China.

Authors

-

External PublicationPutin and Xi's evolving disinformation playbooks pose new threats

External PublicationPutin and Xi's evolving disinformation playbooks pose new threatsAs the information domain becomes an increasingly active and consequential realm of state competition, China and Russia have developed sophisticated information strategies to advance their geopolitical interests, and their playbooks are evolving.

Authors

-

TechStreamHow Biden can make his internet freedom agenda a success

TechStreamHow Biden can make his internet freedom agenda a successThe decision to delay the launch of the Alliance for the Future of the Internet offers the Biden administration an opportunity to better ground it in existing human rights norms. If established thoughtfully, the alliance could play an important role in pushing back on autocratic efforts to reshape the internet into an instrument of state control.

Authors

-

BlogThe internet is a battleground. Will democracies win?

BlogThe internet is a battleground. Will democracies win?Autocracies and democracies have competing visions of what the global online landscape should look like. U.S. President Joe Biden's Summit for Democracy is an opportunity to take an assertive stance against disinformation and the suppression of independent media.

Authors

-

TechStreamHow the Kremlin has weaponized the Facebook files

TechStreamHow the Kremlin has weaponized the Facebook filesFacebook whistleblower Frances Haugen delivered damning testimony to lawmakers in Washington, London, and Brussels. In addition to creating a public relations crisis for the social media giant, Haugen's revelations have also resulted in a less expected outcome: Russian propagandists using her testimony for their own ends.

Authors

-

BlogRepackaging Pandora: How Russia’s information apparatus is handling a massive leak of data on offshore finance

BlogRepackaging Pandora: How Russia’s information apparatus is handling a massive leak of data on offshore financeThe Russian state-controlled media response to the Pandora Papers focuses on wrongdoing by Latin American officials, attempts to discredit allegations against individuals linked to the Kremlin, and suggests Washington had a hand in the financial records leak.

Authors

-

External PublicationHow autocrats manipulate online information: Putin’s and Xi’s playbooks

External PublicationHow autocrats manipulate online information: Putin’s and Xi’s playbooksRussia and China each deploy an evolving set of tactics and techniques to advance their geopolitical interests in the information domain. Here's how their strategies are changing – and how democracies can meet the challenge.

Authors

-

External PublicationHow democracies can win an information contest without undercutting their values

External PublicationHow democracies can win an information contest without undercutting their valuesAs cybersecurity threats grow, democracies should avoid borrowing the authoritarians’ playbook. Here’s what democracies need in developing a cyber strategy of their own.

Authors

-

TechStreamLessons from South Korea’s approach to tackling disinformation

TechStreamLessons from South Korea’s approach to tackling disinformationSouth Korea’s approach to fighting disinformation offers lessons for other democracies.

Authors

-

TechStreamHow disinformation evolved in 2020

TechStreamHow disinformation evolved in 2020Facebook and Twitter are increasingly aggressive in attributing disinformation operations to specific actors, and disinformants are evolving in response, outsourcing their work and relying on AI-generated profile photos.

Authors

Technology and Malicious Actors

Emerging technologies have introduced new capabilities for both state and non-state malicious actors, potentially altering dynamics between them. What cybercrime threats do criminal and militant actors pose to private and government institutions and publics and how will those challenges evolve over the coming decade? How have governments incorporated AI and cyber-driven surveillance technology into policing and counterterrorism? What threats and costs does the government adoption of such technologies carry for civil liberties and human rights across the globe? This workstream is a partnership with the Brookings Initiative on Nonstate Armed Actors.

-

ReportDemocratizing harm: Artificial intelligence in the hands of nonstate actors

ReportDemocratizing harm: Artificial intelligence in the hands of nonstate actorsAdvances in artificial intelligence (AI) have lowered the barrier to entry for both its constructive and destructive uses. As the technology evolves and proliferates, democratic societies need to understand the threat.

Authors

-

EventNonstate armed actors and the US Global Fragility Strategy: Challenges and opportunities

EventNonstate armed actors and the US Global Fragility Strategy: Challenges and opportunitiesOn February 18, the Initiative on Nonstate Armed Actors at Brookings held a panel discussion examining how the U.S. government should think about working with, and through, nonstate armed actors in implementing global fragility strategy.

Information

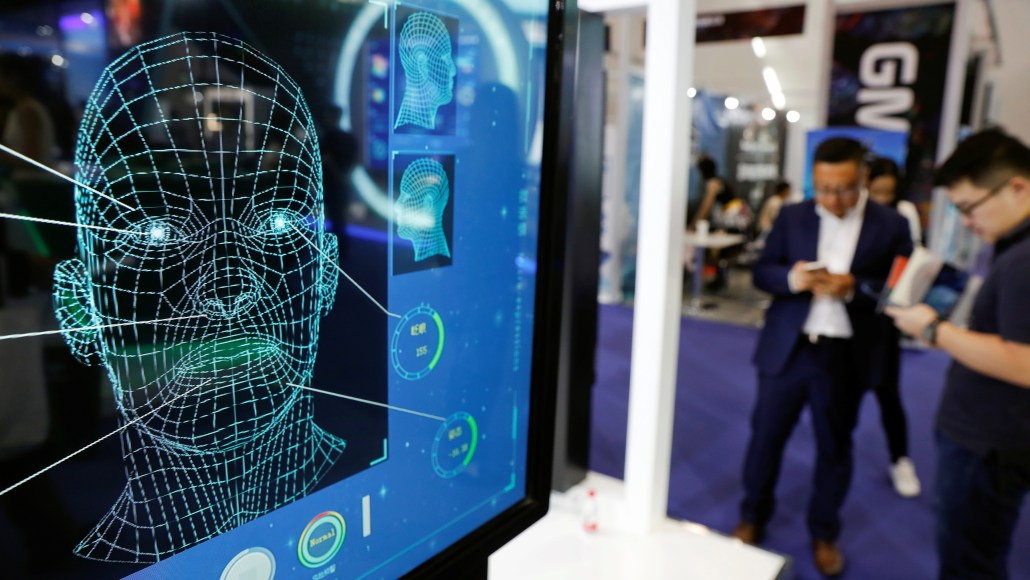

Technology and Surveillance

Advances in facial recognition technology and related systems are increasingly used to track and identify individuals in the real world in real time. These systems can be used to find missing children and persons, but can also be deployed for mass surveillance, to keep tabs on dissidents and opposition leaders, or track journalists and civil society leaders. What are the implications of new facial recognition and surveillance technologies and what global standards should be developed for their use? What can U.S. policymakers learn from their European Commission counterparts’ efforts to regulate facial recognition and other biometric technologies? What policy, legal, and regulatory actions can mitigate unfair practices?

-

ReportPolice surveillance and facial recognition: Why data privacy is imperative for communities of color

ReportPolice surveillance and facial recognition: Why data privacy is imperative for communities of colorDr. Nicol Turner Lee and Caitlin Chin make a case for stronger federal privacy protections to mitigate high risks associated with the development and procurement of surveillance technologies which disproportionately impact marginalized populations.

Authors

-

TechStreamHow digital espionage tools exacerbate authoritarianism across Africa

TechStreamHow digital espionage tools exacerbate authoritarianism across AfricaRecent reporting about NSO Group’s surveillance tools — dubbed the “Pegasus Project”— makes clear that governments across Africa are also using spyware for purposes of international espionage. And these tools are being used in ways that risk worsening authoritarian tendencies and raise questions about whether security services are being properly held to account for their use.

Authors

-

BlogWhy President Biden should ban affective computing in federal law enforcement

BlogWhy President Biden should ban affective computing in federal law enforcementPresident Biden should ban the use of affective computing in law enforcement application to preempt the use of unproven, proto-dystopian technologies, Alex Engler writes. Despite the high stakes and lack of efficacy, the ease of access to affective computing has already led to law enforcement use.

Authors

-

BlogMandating fairness and accuracy assessments for law enforcement facial recognition systems

BlogMandating fairness and accuracy assessments for law enforcement facial recognition systemsFacial recognition systems should be tested for fairness and accuracy limitations prior to use by law enforcement, writes Mark MacCarthy.

Authors

-

BlogDigital fingerprints are identifying Capitol rioters

BlogDigital fingerprints are identifying Capitol riotersRecent years have seen a dramatic flourishing of digital technologies. People are communicating via social media sites and text messages, exchanging money and finding lodgings online, and posting pictures and videos that document when, where, and at what time they engaged in various activities. Following the mob violence at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, it, therefore, is not surprising that many of these tools have been deployed to identify rioters, find those who engaged in violence and vandalism, and use that evidence to indict suspects. Taken together, the information gathered before, during, and after the riot demonstrates how technology enables both insurrection and legal accountability.

Authors

-

TechStreamHow regulators can get facial recognition technology right

TechStreamHow regulators can get facial recognition technology rightAs facial recognition technology spreads, regulators have tools to ensure that this technology does not result in inaccurate or biased outcomes.