If the polls leading up to the second GOP presidential debate indicate one thing, it is that confidence in the political system among Republicans has collapsed. Two candidates that possess no political experience at all—Donald Trump and Ben Carson—combine for over 50 percent of the vote in the most recent ABC News/Washington Post poll.

Put another way, the other 14 candidates—all but one of which is a current or former office holder—combine for less than 50 percent of the vote. Not one of them attracts even 10 percent support. These results are staggering.

The existence of an anti-Washington bias is not new for either party. Because a former U.S. Senator presently sits in the White House, it is easy to forget that the last sitting Senator to be elected president before him was John F. Kennedy in 1960. The one before that was Warren Harding in 1920.

Usually a candidate is outsider enough if he was or is a governor. There is no shortage of them in the race—Bush, Walker, Kasich, Jindal, Huckabee, Christie, Pataki, and Gilmore (and until last week, Perry). The shocking thing is that all but Bush (who has only 8 percent support) are running behind the combination of “None of these” and “unsure.”

What is so different now than before?

Much has changed, of course, but the most important thing is that, since the beginning of survey research in the 1940s, levels of trust in government have never been lower than they are now among Republicans.

The most common question that pollsters ask to gauge political trust is the following: “How much of the time do you think you can trust the government in Washington to do what is right, just about always, most of the time, or only some of the time.” Over most of the last seven years, it is common for fewer than 10 percent of Republicans in the electorate to answer either “most of the time” or “just about always.”

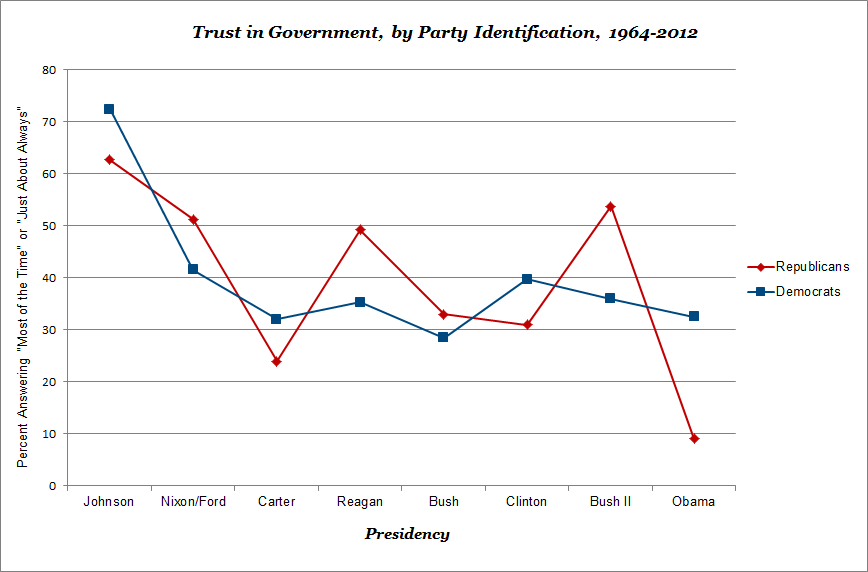

It is not just that this number is a little lower than usual. When George W. Bush was president, that figure was often above 50. And, even when Bill Clinton was president, it was usually around 30 percent. The figure below traces the trend in this survey question over time.

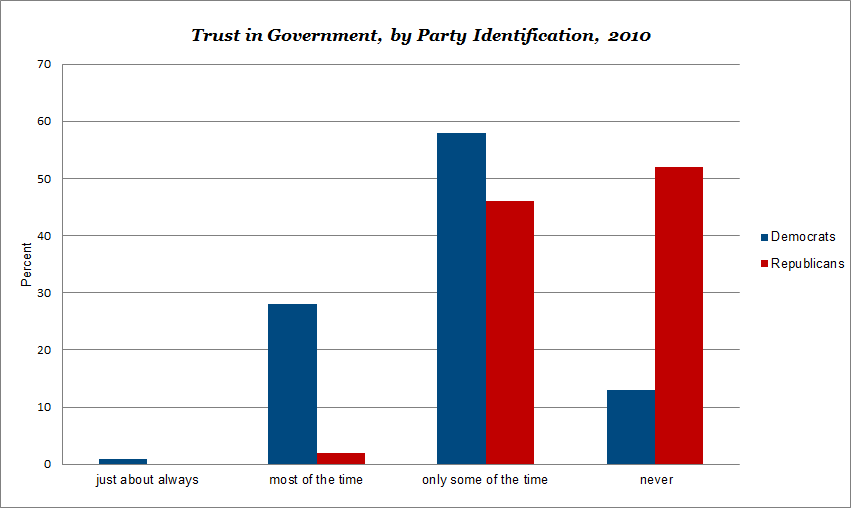

One thing the over time trend fails to capture is the intensity of the distrust today. To say that one trust’s the government in Washington “only some of the time” is not to express extreme cynicism. In a survey fielded in 2010, however, we asked the classic trust in government question, but offered respondents an opportunity to say “never” in addition to the usual three options. As the figure below shows, “never” trusting the government was, to say the least, a popular option among Republicans. Greater than 50 percent said never.

Not only does the collapse in trust shape which presidential candidates Republicans prefer, it is key to understanding the political dysfunction and gridlock that has gripped the U.S. for the past decades. This is the argument that my co-author Tom Rudolph and I make in our new book, Why Washington Won’t Work: Polarization, Political Trust and the Governing Crisis.

When hardly anyone from the party opposite the president trusts the government, governance becomes all but impossible. It is this group who must make sacrifices to support the president on an issue. Such ideological sacrifices require trust.

An example helps illustrate the argument. Republicans are averse to big government initiatives. To support more government, such as providing economic stimulus during a downturn, requires them to trust the government enough to think that making such a sacrifice to their general ideological orientation will make things better, not worse. Absent that trust from the other side of the political divide, a president cannot generate anything approaching consensus in the mass public for his initiatives. We show this is true whether a Democrat or a Republican is in the White House.

Ronald Reagan’s presidency illustrates how important getting public support of people from the other party can be. It is the grease that allows the public to nudge elected officials from polarization to productivity. It is relatively easy for the president to get his own side to follow along. But at least a decent-sized chunk of people from the other side need to buy in as well.

That is because elected officials respond most to those they expect will be their supporters the next time they face the voters. Today, lockstep Democratic support in the electorate will not do anything to push Republicans in Congress to support a policy, because they are not going to be GOP voters in the next election.

Without trust in government, Democrats today (and Republicans during the late Bush years) could not get people from the opposite party to give their ideas a shot. As a result there is no pressure on members of Congress to do anything other than follow their party leaders. Gridlock ensues. Nothing gets done.

Of course, the public is much more moderate than those they elect. A gridlocked political system is not their first choice. But letting the other side—a group they profoundly dislike and distrust these days—win a victory would be even worse. People do not encourage compromise with those they do not trust.

Whoever emerges from this mess of a primary election field will face the same challenges. This will be true whether it ends up being an anti-politics candidate like Donald Trump or Ben Carson or an establishment candidate like Jeb Bush or John Kasich. Ordinary Americans are too distrustful of their opponents for the system to work very well. Donald Trump is not going to change that.

» More information about the book, Why Washington Won’t Work: Polarization, Political Trust and the Governing Crisis, is available here.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Trust in Trump comes from lack of trust in government

September 16, 2015