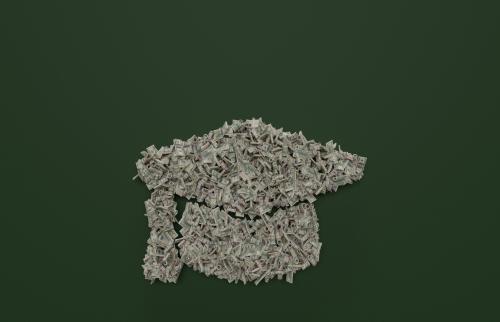

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) will cut taxes by almost $1.5 trillion over the next decade, largely benefiting corporations, pass-through businesses such as partnerships, and people who inherit large estates. The bill will also provide modest tax reductions for most wage and salary earners.

Though some households will do better than others, it sounds like almost everyone is a winner at first glance. But tax cuts are not free; they eventually have to be financed with higher taxes or lower spending. And once those financing requirements are taken into account, most low- and middle-income households are likely to be worse off than they would have been without the tax cut in the first place.

Previous TPC analysis shows that households in every income group will be better off on average due to the direct provisions of the tax cut. However, after accounting for a plausible financing mechanism—in which the tax cuts would be paid for with equal-per-household increases in taxes or reductions in benefits—many low- and middle-income households will lose more than what they gain from the tax cuts themselves.

For example, in 2018, the TCJA will raise average after-tax income for households in every income group. Households in the lowest 20 percent of the income distribution (about $25,000 or less) will receive an average tax cut of $60, while those in the top 0.1 percent (with income of $3.4 million or more) will get an average tax cut of about $193,000. After-tax income will rise by 0.4 percent on average for households in the bottom quintile and by 2.7 percent for the top 0.1 percent of the income distribution. Overall, 80 percent of households will receive a tax cut in 2018, while 5 percent will pay more in taxes.

However, the distributional outcomes change dramatically once you take into account how to pay for the tax cuts. Building on our earlier work that examines the role of financing, we assume that each household pays the same dollar amount to cover the cost of the tax cut. This might occur through a combination of cuts in government spending (which would mainly affect low-income and to some extent middle-income households) coupled with an income tax increase (which would mainly affect high-income households).

Under the equal-dollars-per-household financing scenario, each household would have to pay about $1,610 in 2018 to cover the costs of the tax cuts in that year. As a result, the combination of the tax cuts and the financing raises net burdens on the bottom 60 percent of households on average (Table 1). After-tax incomes for the bottom 20 percent would decline by an average of 11 percent, or $1,560 (rounding to the nearest $10). Average after-tax income would fall by 1.2 percent, or $690, for middle-income households.

On the other hand, households in the top 40 percent would be better off on average after the financing is included (relative to a baseline without the tax cuts). Those in the top 0.1 percent would still gain, on average, more than $190,000.

Overall, more than 74 percent of households, including nearly all in the bottom two quintiles, would experience a net tax increase (formally, a reduction of income net of taxes and benefits) under this scenario. This is in sharp contrast to the 80 percent of households who would receive a tax cut in 2018 before taking financing into account.

Republican leaders in Congress have suggested they will turn to cutting welfare and programs such as Medicare and Medicaid once a tax bill is complete. If Congress follows this strategy, the effects of the tax cuts plus their financing would be even more regressive than the equal-dollars-per-household scenario we review.

Our estimates do not account for potential economic growth effects because several recent studies suggest they would be relatively small and are unlikely to change the basic conclusion much. We also do not estimate the distributional impact of the repeal of the Affordable Care Act individual mandate. Including that provision would make the legislation and its subsequent financing substantially more regressive.

The direct effects of the TCJA will generally provide tax cuts to most households but much larger tax cuts by most metrics to the highest-income households than to others. Once the tax cuts are financed in a way that resembles recent Administration and congressional budget proposals, the effects of the TCJA become more regressive: low- and middle-income households will end up worse off than they would without the tax cuts in the first place.

Commentary

Once the tax bill is paid for, low- and middle-income households will be worse off

January 2, 2018