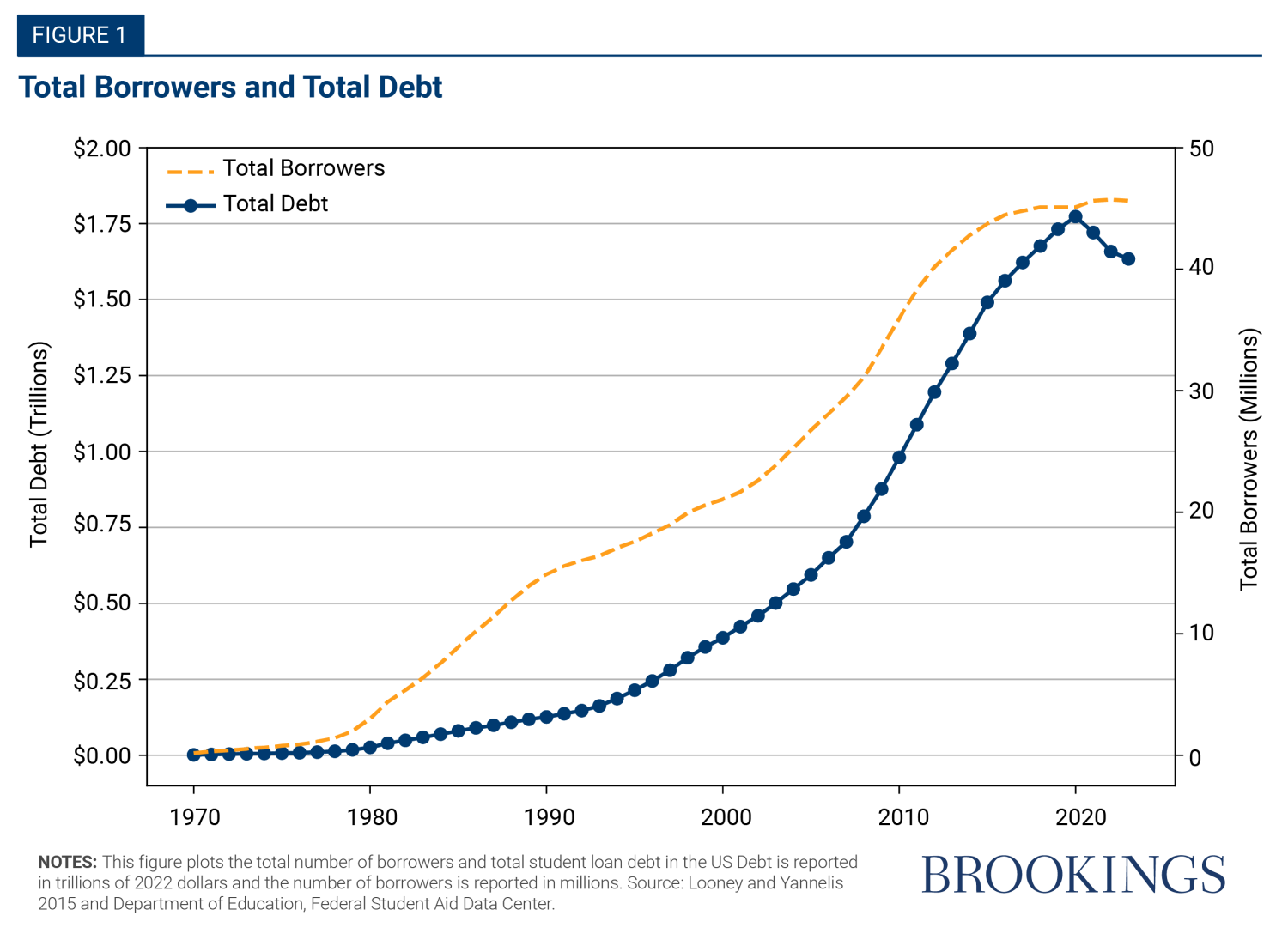

Between 2000 and 2020, the total number of Americans owing federal student loans more than doubled from 21 million to 45 million, and the total amount they owed more than quadrupled from $387 billion to $1.8 trillion, growing much faster than any other form of household debt. Figure 1 shows the growth in student loan borrowers and balances.

Prior to 2020, when payments were temporarily frozen, a million students defaulted each year, and millions more struggled with their loans and failed to make payments. As recently as 2018, the Congressional Budget Office expected taxpayers to earn a profit on federal student lending programs. It now expects new loans issued over the next decade will instead cost $393 billion—more than will be spent on Pell grants for low-income undergraduates (Congressional Budget Office 2024). Moreover, that prospective cost estimate excludes hundreds of billions of write-downs on existing loans expected because of new policies that will reduce borrowers’ payments and provide debt forgiveness. Compounding these financial costs, many students left college without a degree or with a degree of dubious value, having missed out on the opportunity to rise up the economic ladder. What went wrong?

Since federal student lending programs started in the 1950s, such programs have exhibited boom-and-bust credit cycles. Legislation expanding financial aid to increase educational opportunities led to increased enrollment but also to the proliferation and expansion of institutions providing low-quality education to riskier students. The subsequent deterioration of student outcomes—and reports of scandals—caused Congress to limit lending using so-called “accountability rules,” regulating how postsecondary institutions participate in federal lending programs. When these new rules constrained opportunities for some would-be students, Congress would then whittle away at the rules, allowing student loans to expand again, until a new range of concerns appeared.

After a previous student loan crisis in the 1980s was arrested by new accountability rules passed by Congress, those rules were gradually loosened in the late 1990s. Almost immediately, college enrollment and student borrowing accelerated, particularly among groups that had historically been underrepresented at traditional institutions—students who were lower-income; first-generation students; Black and Hispanic; older; enrolled less than full time; pursuing degrees other than a B.A.; and much more likely to rely on federal aid not just for tuition but also for other costs of attendance, like living expenses. Expanding educational opportunities for these groups is clearly desirable and a key purpose of financial aid programs. But from the perspective of student lending, these new borrowers were much riskier, partly because of their socioeconomic backgrounds and partly because of the institutions they attended.

The institutions that enrolled this new wave of borrowers were disproportionately not traditional four-year institutions with strong educational and economic outcomes. Starting around 2000, for-profit institutions tripled their enrollment and community college students tripled their rate of borrowing. In 2000, only one of the top ten schools in terms of aggregate student loan volume was for-profit. By 2014, for-profits accounted for eight of the ten schools whose students owed the most (Looney and Yannelis 2015). In general, the schools that enrolled the surge of new students were those with high default rates and low student loan repayment rates, where few students complete their intended degrees, or where graduates’ earnings are the lowest. This influx of disadvantaged borrowers to lower-quality schools was catastrophic for those students’ finances, aggregate student loan outcomes, and the federal student loan budget. Between 2000 and 2014, the student loan default rate rose by 75% (Looney and Yannelis 2015).

Today’s student loan crisis—and the fact that it is one of a series—highlights the challenges of using a student loan financial aid system to promote access to educational opportunities that vary enormously (but in opaque ways) in their quality, value, and student outcomes. Today, the student loan program is the most costly federal program for subsidizing higher education. In contrast to other federal aid to students, however, loan eligibility is not means tested, and few guardrails exist to prevent using loans to pursue low-quality or excessively costly programs. As a result, the program’s budget cost and its distributional effects are delegated to the program’s beneficiaries themselves—the institutions, which enroll students and set the cost of attendance, and the students, who decide where to enroll and how much to borrow. Schools’ payments are only very weakly linked to students’ outcomes. As a result of these misaligned incentives, students—particularly disadvantaged students and those historically underrepresented at universities—face high costs, variable quality, and inequity in who goes to college and graduate school.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The Brookings Institution is financed through the support of a diverse array of foundations, corporations, governments, individuals, as well as an endowment. A list of donors can be found in our annual reports published online here. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are solely those of its author(s) and are not influenced by any donation.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).