Is the Senate immigration bill doomed to failure? Representative Luis Gutierrez (D-Ill.) says no – he claims that there are 40 to 50 Republicans who are ready and willing to vote in favor of comprehensive immigration reform if it comes to a vote on the House floor – far more than are necessary for the measure to pass. In a recent interview with the Washington Post, he said “Some of them I’ve spoken to, and they say, ‘Love to do the activity with you, I want to be able to vote for it, I really don’t need to draw attention to myself at this point,’ but we can count on it.”

The problem is that the odds of immigration reform coming to a House vote increase tremendously if those moderate Republicans are willing to draw attention to themselves. Speaker Boehner has declared that he will invoke the Hastert Rule – under which no bill comes to a vote without the support of the majority of the majority party – in order to block a vote on comprehensive immigration reform. With the bill stuck in Republican-dominated committees, the clearest path to the floor will likely involve a discharge petition.

Discharge petitions are markedly more successful when they are initiated or threatened by members of the majority party. So, regardless of whether the Democrats need 2 Republicans or 200 to reach the requisite 218 signatures, the leadership will take the threat much more seriously if it is coming from a member of their own party rather than from minority leader Nancy Pelosi (though Democratic leaders are, themselves, reluctant to initiate a discharge petition for fear that doing so will ruin the possibility of a compromise).

Discharge petitions are markedly more successful when they are initiated or threatened by members of the majority party.

Since 2002, 74 discharge petitions have been introduced. None have received the requisite number of signatures to progress to a floor vote. And all but one of those petitions was initiated by a member of the minority party.

Only three bills have been successfully discharged from committee to eventually become public law. The release of the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938 was initiated by Mary Norton, a Democrat and a member of the majority party in the 75th Congress. In 1950, T.A. Thompson, also a member of the Democratic majority, initiated a discharge petition that eventually freed the Fair Labor Standards Act from committee so that it too could become public law. In 1963, the mere threat of a successful discharge petition was enough to shake lose the Civil Rights Bill; that petition was initiated by House Judiciary Committee chairman and majority party member Emanuel Celler.

The most recent successful discharge petition allowed the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act to become law. And, in fact, this is the one case in which a majority party member did not initiate the petition (perhaps since, after reform in 1993, signatories were not longer shielded by anonymity). The Senate approved the McCain-Feingold bill on April 2, 2001 by a vote of 59-41. A similar version of the bill was transmitted to the House Administration Committee. The committee favorably reported a significantly weaker version of the bill, and proposed a rule for debate that would require separate votes on each of the provisions that would make the House version of the bill conform to the Senate version. The House voted 228-203 to reject the rule proposed by the House leadership (notably, with Hastert at the helm). A week later, the discharge process began with the goal of bringing a bill similar to the Senate version to the House floor.

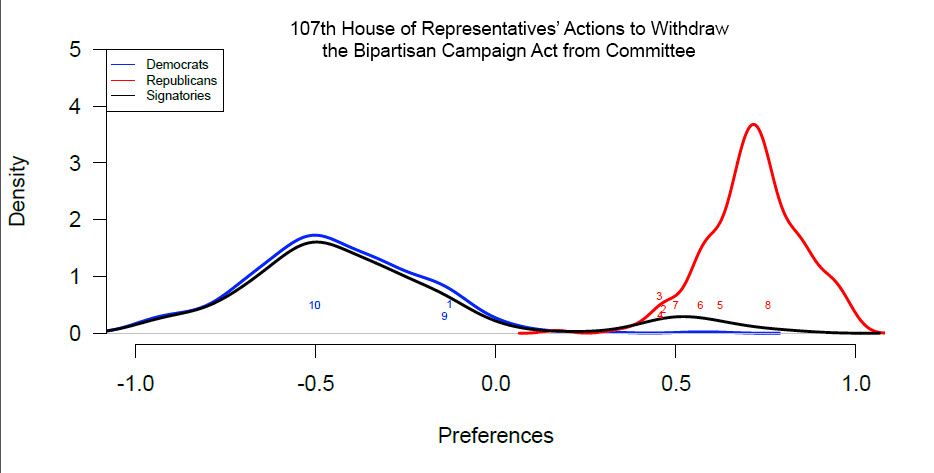

The figure below can give us some insight into who wanted to withdraw the Bipartisan Campaign Act from committee. The blue line shows the preferences of all the Democrats in the 107th House, the red all the Republicans, and the black all the discharge petition signatories. Finally, the numbers at the bottom show the order in which the first ten legislators signed the petition, with red and blue indicating Republicans and Democrats, respectively. Clearly, there was a large coalition of Democrats who wanted to see a vote on campaign finance reform. And, as previously mentioned, the discharge petition was initiated by a Blue Dog Democrat: Jim Turner of the 2nd District in Texas. Importantly, signatures two through eight came from within the Republican ranks. The Democrats held 213 seats in the House at the time, so they only needed 5 Republican signatories for the petition to go through; ultimately, 22 Republicans defied their caucus and supported the discharge petition. So, even though it was a moderate Democrat who initiated the discharge process, he had the explicit support of moderate Republicans.

If moderate members of the GOP support comprehensive immigration reform – as Gutierrez claims they do – why are they so reluctant to threaten or initiate the committee discharge process? The reason is that the invocation of the discharge rule does not really benefit anyone. The leadership is engaged in a game of chicken with the more moderate members of its party. Moderate legislators benefits from having the party leadership on their side – they get more PAC contributions, better committee assignments, and other perks. However, moderate Republicans have their own policy interests; they have to appease their constituents and their consciences, which may lead them to butt heads with the less moderate members of their party. The leadership, for its part, wants to maintain the party’s brand – party unity is good for winning elections, and a public battle over a discharge petition pits different factions of the party against one another. Moreover, the invocation of the discharge procedure undermines the majority party’s agenda-setting authority, which is a dangerous precedent to set. So, neither the leadership nor the moderate members of the majority party want the discharge procedure used—suggesting that we should rarely see it employed (which is what we typically observe). Instead, the potential for a discharge petition is often sufficient to force the leadership to report a bill.

In sum, the leadership and the median legislator both prefer to avoid committee discharge. But the chamber majority only gets the upper hand if the leadership believes that it will use the discharge rule to release bills it supports from committee. In today’s House, the current leadership appears to believe – and perhaps correctly so – that the moderate members of its party (whose support would be necessary for the execution of the discharge rule) prefer to toe the party line rather than get a policy that is closer to their preferred outcome. If moderate members of the majority party are unwilling to defy their leadership, committee discharge is not a credible threat, and will not serve as a check against a majority party determined to block a bipartisan bill. If so, we should not expect the Senate immigration bill to emerge from a House committee any time soon.

If moderate members of the majority party are unwilling to defy their leadership, committee discharge is not a credible threat, and will not serve as a check against a majority party determined to block a bipartisan bill.

Nevertheless, as the political standoff on immigration reform continues, committee discharge may be an increasingly appealing option for a coalition of Democrats and outspoken moderate Republicans. As political pressure mounts, the mere threat of a discharge petition may be sufficient to force a vote on immigration reform. The public wants this bill to pass – a recent

Gallup poll

showed that 86% of both Democrats and Republicans support the controversial path to citizenship for undocumented workers that House Republicans vehemently oppose. As legislators head home for summer this year, Obama, Democratic leaders, and Republican supporters of the bill can draw the public’s attention back to the issue of immigration reform to remind constituents to put pressure on their representatives. Public opinion is a strong motivator, and moderate Republicans may be more willing to defy their caucus if their constituents make their preferences for immigration reform known. So, hope is not lost for comprehensive immigration reform. The bill is still very much in play, and the discharge procedure might force the House leaders’ hands, providing a path to immigration reform.

Commentary

How the Discharge Petition Can Help Congress Move on Immigration Reform

August 19, 2013