A version of this post originally appeared in CityLab

Richard Florida’s book The New Urban Crisis contains a number of important truths about the challenges facing America’s metropolitan areas. Chief among them is the recognition that prevailing narratives about metropolitan areas in this country are at best only partly accurate. Cities aren’t uniformly places of wealth and abundance, nor are they uniformly in disrepair and decay. Not all suburbs reflect a sunny vision of the American dream. And even the most prosperous metro areas are riven with disparities by race, class, and place.

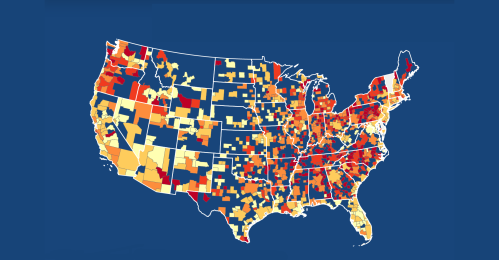

Instead, our country is divided into neighborhoods of concentrated advantage and concentrated disadvantage that exist across the urban-suburban-rural continuum, forming a pattern that Florida calls the “Patchwork Metropolis.” Finding ways to bridge these divides and enable more people and places to benefit from economic growth lies at the heart of the New Urban Crisis.

Florida argues that we need more urbanism to move our country forward. In fact, what we need is more regionalism.

Among some local leaders, the very notion of regionalism elicits resistance. It’s often viewed as too idealistic and complex. The costs of wrangling people and organizations together across multiple counties or sectors to improve economic opportunity seem to outweigh the benefits. Yet the scale and cross-cutting nature of the New Urban Crisis suggests we can’t do more of the same: The pursuit of inclusive growth will fail if leaders’ mindsets and strategies remain siloed within jurisdictions and sectors.

What’s promising is that an increasing number of local leaders are beginning to realize they must think and act regionally. These leaders are getting out of their comfort zones, listening to new voices, and forging unusual alliances to pursue inclusive growth on a regional scale. They are designing integrated initiatives despite disincentives within programs to do so. Here are four ways that public and private sector leaders in metro areas have demonstrated how to do it.

1) Make the case

In Chicago a coalition of civic, philanthropic, and government actors, led by the Metropolitan Planning Council and the Urban Institute, found that the area’s extreme segregation costs everyone in the region. Their report estimated that were Chicago able to reduce its segregation to that of a typical U.S. metro area, the region would generate an additional $4.4 billion annually in wages and see its homicide rate decline by 30 percent. Committees of diverse organizations are now working on strategies to act on the report’s findings.

2) Engage voters

Leaders in the Denver metro area believe that asking voters to support regional assets like a modern international airport or regional transit system through ballot initiatives has dual benefits. It creates dedicated funding sources for regional infrastructure, and more importantly, it creates a metropolitan-wide conversation. Greater Seattle and Indianapolis have followed Denver’s example: Voters across the three-county Puget Sound region approved of a major transit investment last fall following a campaign jointly spearheaded by elected officials, advocacy groups, and business leaders. Thanks to a similarly cross-sector effort, the combined city-county of Indianapolis/Marion County is moving forward with an ambitious expansion of their bus network.

3) Collaborate region-wide

WorkAdvance, a national pilot program in four regions including Northeast Ohio, aligned previously siloed workforce development systems within each region around common standards and high-value sectors. An independent review of the program after five years found that this collaborative effort succeeded in improving employment rates and earnings compared with a control group. Five workforce boards in Northeast Ohio, representing five adjacent counties, have since announced plans to expand upon the efforts of the pilot program. And Chicago’s Regional Housing Initiative, which brings together the area’s 7-county planning agency, the state housing agency, and 10 area public housing authorities, expands the supply of affordable housing in opportunity-rich neighborhoods by pooling federal housing vouchers and other financial supports. The unique collaboration has supported more than 2,200 affordable apartments in nearly 40 mixed-income and supportive housing developments, over half of which are in the suburbs where the rental stock is traditionally more limited.

4) Act locally (but connect regionally)

Not every strategy needs to be implemented through multi-jurisdictional collaborations, but the best local and neighborhood strategies reflect broader regional priorities. In Milwaukee, city leaders have organized their neighborhood and land redevelopment strategies around three priority industry clusters identified previously by M7, the region’s seven-county economic development organization. City officials are working to repurpose underutilized industrial corridors to house a water technology incubator, accommodate food and beverage manufacturing firms, and attract engineering startups in the power and energy controls sector. The region’s skills training initiative links low-income residents in adjacent neighborhoods to these three sectors.

No single initiative can bridge the stark income, race, and neighborhood divides in our country. However, these multi-sector, multi-jurisdictional approaches to problem-solving offer our best hope at addressing the set of overlapping challenges: It’s time to fully embrace regional strategies.

Commentary

Cities alone can’t fix the New Urban Crisis

April 25, 2017