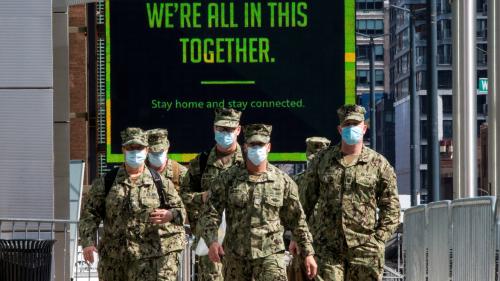

With the saga over the U.S.S. Teddy Roosevelt aircraft carrier starting to fade from the headlines, a larger question about the American armed forces and COVID-19 remains. How will we keep our military combat-ready, and thus fully capable of deterrence globally, until a vaccine is available to our troops? It will also be crucial to sustain activities like the Coast Guard’s inspections of ships inbound for U.S. harbors, Central Command’s counterterrorism operations, and the key roles of the National Guard in responding to the crisis here at home.

To date, it is reasonable to say that the U.S. military has not been severely affected by the novel coronavirus. The preponderance of uniformed personnel and their families are young, which helps of course. On top of that, most of the military is based in reasonably remote parts of the country. So far, there would appear to be some 5,000 diagnosed cases of COVID-19 among some 1.3 million active-duty troops, with a death rate an order of magnitude less than in American society writ large.

Part of the success to date in keeping COVID-19 out of the ranks is due to the prudence of commanders around the country and the world, who have been given flexibility by Secretary of Defense Mark Esper to take measures they deem appropriate. The armed forces have canceled or postponed large-scale exercises that bring together thousands of people in one concentrated locale. Social-distancing protocols have been instituted on bases. Basic training was temporarily suspended or scaled back as new screening and testing protocols were put in place, much of it is already ramping back up. Some services have also suspended certain “permanent change of station” (or PCS) moves. The naval services have been particularly careful not to let sailors and Marines go to sea if sick, since as we all know, ships are the perfect petri dishes for the virus’s spread.

Not all of these measures can be sustained indefinitely. The armed forces will face an increasingly challenging path forward through the rest of the calendar year and into 2021. Yet it is worth signaling to the American people — and to any of the nation’s potential foes — why the resulting strains on readiness, though significant, should be tolerable.

One key structural advantage going forward is that the military is built to deal with attrition, whether from battle or any other cause, and still keep its fighting integrity. Based on the standard shape of pandemic curves, COVID-19 could, in theory, infect 5% or more of the U.S. population at a time (though to date, the total number of cases is still less than 1%, even if we quadruple the official tally). Five percent would be a daunting figure for the nation’s hospitals and health care system. But it would be a manageable number for the military — even if all those infected were unavailable for a stretch of time. For example, the military’s “C-scales” of readiness — the overall way in which the services rate the immediate preparedness of main combat units, usually on a sliding scale of C-1 through C-4 — anticipate degradations of 10-20% in personnel and equipment for various reasons. A unit that began in top shape but then suffered such attrition would still be considered capable, even if weakened.

That said, there are things the military needs to watch, and adjustments it will need to consider in the months ahead:

- One of Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis’s goals when he took the reins of the Pentagon three years ago was to restore mission-capable rates of most combat aircraft fleets to at least 80%. That standard has now largely been attained, after several years of effort. The key now is to prevent equipment maintenance backlogs from developing, given the long recovery time associated with such backlogs.

- Pilots need to fly to stay safe. Modern simulators are outstanding, but no substitute for a certain amount of the real thing, especially for young pilots. The same principle applies to other types of dangerous activities where, like with parachuting, you must get in a certain number of “reps” each week or month to stay proficient.

- The pipeline of new recruits must continue apace. Today’s American armed forces bring in 15-20% of their total personnel strength each year (meaning they also lose 15-20% of existing personnel per year to retirement or the end of normal tours and enlistments). So far, it appears digital recruiting and other efforts continue to meet or exceed goals, and a challenging U.S. economy will likely aid recruiting and retention in the months ahead. Still, leaders must remain watchful that they are meeting targets.

Some ships will need to set out on new deployments. The U.S. Navy typically has 50 or more ships at sea at a time. With 6- to 7-month deployments the norm, that translates into sending out 6 to 10 ships per month to spell those finishing their own tours. That pace can be adjusted, and temporarily relaxed if need be — indeed, the COVID-19 crisis provides an opportunity to rethink some standard ways of doing business. But there is little doubt that at least several ships per month will need to be embarked on new deployments.

Soldiers and Marines are continuing today to train at the squad, platoon, and company levels, while also maintaining marksmanship and other core skills. But the nature of modern combined-arms warfare requires that a training cycle include at least occasional exercises at higher echelons of battalion and brigade (or regiment) as well.

As with much of the rest of society, the key to effectiveness in the above tasks will be widespread testing, especially for those in close quarters. Fortunately, the availability of testing should increase substantially over the very time frame over which most readiness concerns will intensify. That fact, combined with a military culture that will adapt as always to adverse conditions, bodes well for future U.S. military readiness even in these most challenging times.

The views here do not necessarily reflect those of the Departments of the Army, Navy, Air Force, Defense, or Homeland Security/Coast Guard.

Commentary

COVID-19 and military readiness: Preparing for the long game

April 22, 2020