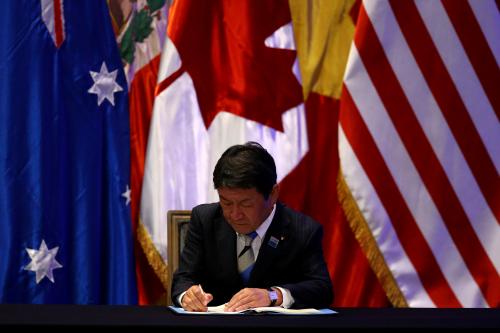

On April 15 and 16, Japan’s Economy Minister Toshimitsu Motegi meets with U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer in Washington for the first round of bilateral trade negotiations. Both sides should move to strike a deal quickly, writes Mireya Solís, in order to avoid numerous pitfalls that could arise with prolonged negotiations. This piece originally appeared in Vol. 2 Issue 4 of the series “Debating Japan” from the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) on April 15.

U.S.-Japan trade talks have been moving in slow motion. The agreement both sides hammered out as part of the larger Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) undertaking became moot after President Trump swiftly withdrew the United States from the deal. Tokyo did not agree with the notion that a bilateral trade agreement—negotiated under the auspices of an “America First” doctrine—would offer a better alternative, and its eventual nod aimed mostly to forestall the possibility of tariff hikes on automobiles under the pretense of safeguarding U.S. national security. Last fall, bilateral trade talks received clearance at the highest level with a Trump-Abe joint statement carefully referencing sensitive areas for each side (agricultural opening for Japan, automobile manufacturing for the United States) in an effort to smooth the way for negotiations. But no trade talks ensued. The United States became consumed with its bilateral quest to cajole structural reforms from China, and Japan was none too eager to put the bilateral talks on the front burner.

With the opening round of trade negotiations, however, both sides will be better served by a quick sprint to the finish line. Protracted negotiations carry significant risks: the re-emergence of trade friction with old irritants (rice and cars) dominating the economic dialogue; the sidelining of U.S. farmers as producers from the relaunched TPP use tariff benefits to briskly increase their market share in Japan; the danger of severe economic dislocation at both ends of the Pacific if President Trump were to pull the trigger on auto tariffs out of frustration with stalled talks; and if these scenarios materialize, the overall deterioration in U.S.-Japan relations with a breach of trust and a diminished sense of shared economic interests between the two allies.

A fast outcome on bilateral trade talks should not be pinned on the false hope of replicating the TPP exercise at the bilateral level. A “TPP for two” is not in the cards; both sides have moved on. Japan has consolidated its position as a leader in rules-based trade liberalization with two mega trade agreements under its belt: the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the Japan-EU Economic Partnership. In contrast, the current U.S. administration touts the benefits of bilateral deals with the primary goal of reducing trade deficits, has resuscitated managed trade practices through quotas, and has actively used tariffs (or the threats of tariffs) to gain leverage in negotiations and to protect specific sectors.

Without a doubt, the bilateral trade negotiations will be vexing. Both parties first have to agree on the sheer scope of talks (goods plus a few services or a full-fledged free trade agreement (FTA)); and a number of red flags for negotiators are already visible: export restraints on autos, binding currency rules in the body of the agreement, agricultural liberalization beyond TPP levels, and the potential adoption of a clause discouraging trade negotiations with non-market economies that surely lands flat as Prime Minister Abe aims to put relations with China on better footing. Still, speed is good counsel.

A timely conclusion of negotiations has two major upsides. First, speed can improve the quality of the bilateral trade agreement because it will encourage compromise. The contours of that compromise are not hard to fathom: to set aside trade-reducing demands (quotas that cut back Japanese automobile exports to the United States) to enable a brisk negotiation result leveling the playing field for U.S. producers in the Japanese agricultural market. This bargain is not a pipe dream, keeping in mind that the 232 report on auto tariffs has already achieved what U.S. Trade Representative Lighthizer intended (bringing reluctant parties to the negotiation table), but there is no domestic constituency for the actual implementation of tariff hikes that would wreak economic havoc. A quick result on agricultural opening is important to the Trump administration as the fate of the United States-Mexico-Canada trade deal is more than uncertain, the “historic” deal with China may not lead to a swift lifting of tariffs, and the retaliatory measures applied by several nations in the wake of U.S. tariffs on metals are still biting.

Second, once the United States and Japan get past the bilateral trade talks, they will be better poised to shape together Asia’s economic architecture. Both sides share an abiding interest in preserving and expanding an open digital economy, codifying and disseminating rules that address the distortions of state capitalism (disciplines on state-owned enterprises and industrial subsidies, rooting out forced technology transfers, etc.), and pooling resources to finance critical infrastructure in the region to improve development outcomes and avoid overdependence on the Belt and Road Initiative.

Bilateral trade negotiations can be a dead weight if they tie the United States and Japan to a perennial wrangling over tariffs and quotas, or they can be a stepping stone toward coordinated economic statecraft. What will it be, Washington?

Commentary

Why Japan and the US should strike a quick bilateral trade deal

April 15, 2019