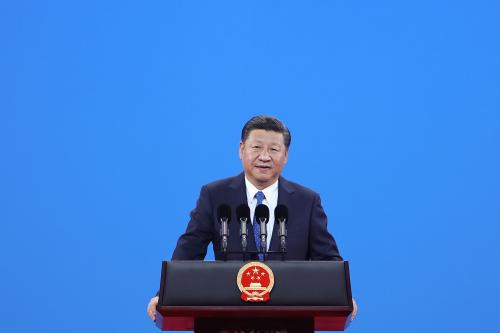

On October 18, General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Xi Jinping delivered a sweeping address on all the policy issues facing the Chinese government and stated his vision for the country’s future. The speech—delivered to the assembled 19th Party Congress—laid out the work of the party central committee that was selected five years ago.

Reporters have been busily trying to interpret the import of what Xi said. Observers in Taiwan have understandably been trying to divine the implications of his statements concerning Taiwan policy. The tendency is to cite this or that sentence and speculate on whether Xi will pursue a tougher policy or not.

In a recent post, I presented a framework for interpreting what Xi Jinping would say about Taiwan. The premise of that framework is that the general secretary’s report is a document written by a committee that follows an institutionalized and iterative process. The committee circulates its drafts widely and then considers opinions and recommendations for possible inclusion.

In addition to considering current views on policy issues, including Taiwan, the drafting group also takes account what was said in reports to past congresses. As I noted in my recent post, when it comes to Taiwan policy, there has been striking continuity on nine policy elements in the reports to the 16th Party Congress in 2002; the 17th in 2007; and the 18th in 2012.

At the same time, Xi Jinping is in charge of the Chinese regime. Like his predecessors, he will have the opportunity to put his stamp on the policy formulations on every issue, including Taiwan.

As such, analysts should look both at whether the nine Taiwan elements of past reports appear in Xi Jinping’s report and at what kind of personal stamp he puts on future policy.

Here are the nine continuous elements:

- The guiding principle (fangzhen) of peaceful reunification of Taiwan according to the “One Country, Two Systems” formula and the eight-point proposal enunciated by Jiang Zemin in 1995.

- Adherence to the One China principle, the key point of which is that the territory of Taiwan is within the sovereign territory of China.

- Strong opposition to separatism and Taiwan independence.

- Willingness to have dialogue, exchanges, consultations, and negotiations with any political party that adheres to the One China principle.

- Stress on the idea that the people on Taiwan and people on the mainland are “brothers and sisters of the same blood.”

- Establishing a connection between unification and the cause of “the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.”

- Placing hopes on the Taiwan people as a force to help bring about unification.

- A promise that progress toward unification, and unification itself, will bring material benefits to Taiwan.

- An expression of “utmost sincerity” by Beijing toward the unification project.

Xi Jinping reaffirmed the first six principles but not the last three. Items #8 and #9 are probably not that important in the grand scheme of things. To not reiterate the commitment to “place hopes on the Taiwan people” could be more significant because past statements suggested that Beijing would take into account the views and sentiments of those people. Will popular opinion on Taiwan no longer be a basis for Taiwan policy? Also, it is possible that when Beijing said it would place its hope on the Taiwan people, the people it was taking about were the more conservative voters who supported the island’s conservative parties, particularly the Kuomintang (KMT). Recently, some Chinese scholars have suggested that China should rely much more on its own power to achieve its unification objective and not on political forces within Taiwan.

For those interested in the ins and outs of Chinese elite politics, it’s worth noting that in item #1, the three previous congress reports included Jiang Zemin’s 1995 eight-point proposal as an important basis for policy. Xi Jinping made no reference to the proposal, which tracks with reports that he and Jiang are not on good terms.

Xi Jinping displayed the greatest toughness when talking about the threat of Taiwan independence. In four crisp yet strident sentences, each of which reportedly received applause, he laid down markers:

“We will resolutely uphold national sovereignty and territorial integrity and will never tolerate a repeat of the historical tragedy of a divided country. All activities of splitting the motherland will be resolutely opposed by all the Chinese people. We have firm will, full confidence, and sufficient capability to defeat any form of Taiwan independence secession plot. We will never allow any person, any organization, or any political party to split any part of the Chinese territory from China at any time or in any form.”

Some of these formulations are not new for Xi. He spoke in basically the same terms in November 2016 to Hung Hsiu-chu, then the chairperson of the Kuomintang. But two things are noteworthy. The first is that his language on Taiwan independence was tougher than what his predecessors said the last times that there was a DPP government in power. Second, the “at any time or in any form” formulation echoes the way China’s anti-secession law, enacted in 2005, states the conditions for the use of “non-peaceful means and other necessary measures”: “In the event that the ‘Taiwan independence’ secessionist forces should act under any name or by any means to cause the fact of Taiwan’s secession from China.” (Emphasis added.)

For his coda and to no-one’s surprise, Xi shifted from stridency to his broad vision for China and folded his aspiration for a unified Taiwan into his broad narrative of the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.” To quote:

“We firmly believe that as long as all sons and daughters of China, including compatriots from Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan . . . firmly grasp hold of the destiny of the nation in our own hands, we will be able to joint create a beautiful future of the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.”

For Xi and other Chinese, a China that remains divided cannot be a great China. Xi did not set an explicit deadline for unification, even though he has talked about the need to end delay. But clearly, Taiwan unification is one part of the highly ambitious agenda that Xi has set for himself as China’s leader.

For Xi and other Chinese, a China that remains divided cannot be a great China.

Xi Jinping discussed Taiwan at a fairly high level of abstraction. There was very little discussion of specific policies. The one place where he did say something specific was when he said the mainland would “take the lead in sharing development opportunities with the Taiwan compatriots” and gradually institute national treatment for individuals and entities from Taiwan. But Xi’s predecessors had offered similar incentives.

Finally, Xi did state that Beijing would “respect the current social system in Taiwan and the lifestyles of the Taiwan compatriots.” He decidedly did not say he would respect the opinions of Taiwan citizens. And that is the nub of the matter. In the 2016 elections, Taiwan voters rejected the KMT candidate in favor of Tsai Ing-wen, the leader of the DPP. One reason was a growing fear that the KMT’s policies had made Taiwan too dependent economically on China. But the election of a DPP government does not ipso facto mean that President Tsai is pursuing Taiwan independence, which Xi portrays as a current danger to Chinese interests. Indeed, President Tsai has actually been very cautious in her approach to cross-Strait relations. Polls show that the great majority of Taiwan people oppose independence (just as they oppose unification). Beijing’s “one country, two systems” model for unification is probably less popular today than it was when Deng Xiaoping first proposed it almost 40 years ago, and recent events in Hong Kong have made the model even less popular. Which raises three questions. Do Chinese leaders understand that their own policies have shaped Taiwan’s fears about their intentions? Do Chinese leaders understand that given Taiwan’s democratic system they have no choice but to put their hopes in the Taiwan people? And do they see that there are more likely to advance their long-term goals not by making threats but by giving Taiwan people significant reasons to believe there is a basis for a positive relationship with China?

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

What Xi Jinping said about Taiwan at the 19th Party Congress

October 19, 2017