The idea that the United States can “do no harm” depends on the fiction that the most powerful nation in the world can ever be truly “neutral” in foreign conflicts, not just when it acts, but also when it doesn’t. Shadi Hamid argues that the better, more just world that so many hope for is simply impossible without the use of American military force. This piece originally appeared on The Atlantic.

The eight years of the Obama presidency have offered us a natural experiment of sorts. Not all U.S. presidents are similar on foreign policy, and not all (or any) U.S. presidents are quite like Barack Obama. After two terms of George W. Bush’s aggressive militarism, we have had the opportunity to watch whether attitudes toward the U.S.—and U.S. military force—would change, if circumstances changed. President Obama shared at least some of the assumptions of both the hard Left and foreign-policy realists, that the use of direct U.S. military force abroad, even with the best of intentions, often does more harm then good. Better, then, to “do no harm.”

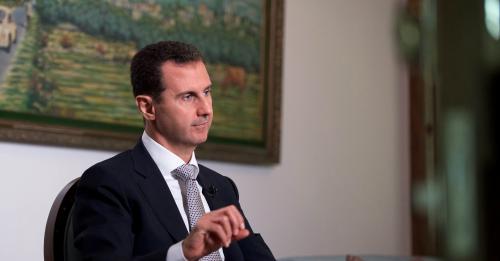

This has been Barack Obama’s position on the Syrian Civil War, the key foreign-policy debate of our time. The president’s discomfort with military action against the Syrian regime seems deep and instinctual and oblivious to changing facts on the ground. When the debate over intervention began, around 5,000 Syrians had been killed. Now it’s close to 500,000. Yet, Obama’s basic orientation toward the Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad has remained unchanged. This suggests that Obama, like many others who oppose U.S. intervention against Assad, is doing so on “principled” or, to put it differently, ideological grounds.

Despite President Obama’s very conscious desire to limit America’s role in the Middle East and to minimize the extent to which U.S. military assets are deployed in the region, there is little evidence that the views of the hard Left and other critics of American power have changed as a result. (Yes, the U.S. military is arguably involved in more countries now than when the Obama administration took office, but—compared to Iraq and Afghanistan before him—Obama’s footprint has been decidedly limited, with a reliance on drone strikes and special-operations forces.) As for those who actually live in the Middle East, a less militaristic America has done little to temper anti-Americanism. In the three countries—Egypt, Jordan, and Lebanon—for which Pew has survey data for both Bush’s last year and either 2014 or 2015, favorability toward the U.S. is significantly worse under Obama today than it was in 2008. Why exactly is up for debate, but we can at the very least say that a drastic drawdown of U.S. military personnel—precisely the policy pushed for by Democrats in the wake of Iraq’s failure—does not seem to have bought America much goodwill.

Despite the fact that Assad and Russia are responsible for indiscriminate attacks on civilians and civilian infrastructure, including hospitals, many leftists have viewed even the mere mention of the U.S. doing anything in response as “warmongering.” We have had the unfortunate situation of someone as (formerly) well-respected as Jeffrey Sachs arguing that the U.S. should provide “air cover and logistical support” to Bashar al-Assad. We have had Wikileaks’ attacks on the White Helmets, who have risked—and, for at least 140, lost—their lives in the worst conditions to save Syrian lives from the rubble of Syrian and Russian bombardment. Of course, it is not an absurd position to be skeptical of any proposed American escalation against Assad, and many reasonable people across the political spectrum have made that case. But it is something else entirely to apply such skepticism selectively to the U.S. and not to others, especially when the others in question deliberately target civilians as a matter of policy. It can be a slippery slope. While no one would accuse Obama of liking Putin, coordinating with and enabling Russia in Syria is effectively U.S. policy. As the New York Times columnist Roger Cohen noted in February, well before the current disaster in Aleppo: “The troubling thing is that the Putin policy on Syria has become hard to distinguish from the Obama policy.”

In Iraq, civil war happened after the U.S. invasion. In Syria, civil war broke out in the absence of U.S. intervention.

The Left has always had a utopian bent, believing that life, not just for Americans, but for millions abroad, can be made better through human agency (rather than, say, simply hoping that the market will self-correct). The problem, though, is that the better, more just world that so many hope for is simply impossible without the use of American military force. At first blush, such a claim might seem self-evidently absurd. Haven’t we all seen what happened in Iraq? The 2003 Iraq invasion was one of the worst strategic blunders in the history of U.S. foreign policy. Yet, it’s not clear what exactly this has to do with the Syrian conflict, which is almost the inverse of the Iraq war. In Iraq, civil war happened after the U.S. invasion. In Syria, civil war broke out in the absence of U.S. intervention.

What all of this suggests is that attitudes toward the U.S. military, and by extension the United States, are often “inelastic,” meaning that what the U.S. actually does or doesn’t do abroad has limited bearing on perceptions of American power. As a general proposition, many leftists, for example, seem to believe that there is something intrinsically wrong with the use of military force by the United States. In other words, when America does it, it is a bad thing, irrespective of the outcomes it produces, and therefore should be opposed outright. There is rarely any real effort to explain why it’s bad—after all, if it were purely a moral stand against the killing of innocents, the use of Russian or Syrian military force would have to be considered much worse.

But, for the use of American power abroad to be intrinsically wrong or immoral, all uses of military force would have to be either immoral or ineffective, or both. However, as a factual matter, this is simply not the case. There was no way to stop mass slaughter and genocide in Bosnia or Kosovo without U.S. military force, buttressed, as it should be, by broad regional or international consensus. In those two cases, a U.S.-led coalition acted. In those cases where the international community did not act, genocide did, in fact, occur, as we witnessed in Rwanda. What became clear then—and what has become clear once again in Syria—is that a world where others than the U.S. take the initiative to stop such slaughter does not exist, and is unlikely to exist at any point in the foreseeable future. While they may be less common, there are also cases where dictators will not only kill their own people but try to forcefully invade and conquer their neighbors. As in the first Gulf War, the gobbling up of Kuwait could not have been prevented without a U.S.-led coalition, again with broad international support.

The list goes on. From a moral standpoint, no one should have to suffer under the indignities of ISIS rule. From a strategic standpoint, having an extremist state the size of Indiana in the middle of the Middle East, needless to say, does not suggest the coming of a better, more secure world. While Obama was late to act against the organization and while the anti-ISIS campaign has been deeply flawed, the amount of territory that ISIS controls has been reduced significantly, due in large part to U.S. airstrikes, intelligence, and special-operations forces. No one, not Turkey, Saudi Arabia, or anyone else, was going to seriously confront ISIS without U.S. coordination and leadership, and it’s U.S. coordination and leadership that is facilitating the current battle for the Islamic State’s Iraqi stronghold in Mosul. This is the faulty—and ultimately quite dangerous—premise behind one of the founding assumptions of Obama’s foreign policy: that if the U.S. steps back, others will step in. Even when “others” do step in, the results are often destructive, since America’s allies and adversaries alike do not generally share its values, interests, or objectives.

Of course, U.S. military force may be necessary, but it can never be sufficient on its own. This is where the judgment, morality, and strategic vision of politicians and policymakers can make the crucial difference. The United States has not been the “force for good” that many Americans would like to think it’s been. There is a tragic history of intervention abroad that more Americans should be aware of, whether it’s overthrowing democratically elected leaders in Latin America or backing brutal dictators in the Middle East. There is no reason to think the U.S. is necessarily doomed to repeat those mistakes indefinitely. But even it was, there would still be instances where only U.S. military force could be counted on to stop genocide.

The alternative to a proactive and internationalist U.S. policy is to “do no harm,” and this might seem a safe fallback position: Foreign countries and cultures are too complicated to understand, so instead of trying to understand them, let’s at least not make the situation worse. The idea that the U.S. can “do no harm,” however, depends on the fiction that the most powerful nation in the world can ever be truly “neutral” in foreign conflicts, not just when it acts, but also when it doesn’t. Neutrality, or silence, is often complicity, something that was once the moral, urgent claim of the Left. The fiction of neutrality is growing more dangerous, as we enter a period of resurgent authoritarianism, anti-refugee incitement, and routine mass killing.

This is the built-in contradiction of what might be called the “anti-imperialist Left.” They are against empire, and there is only one country powerful enough to reasonably be considered “imperial.” (Russia, of course, engages in bloody imperial ventures, but it gets a pass since it is acting against the United States.) But to insist that the fundamental problem in today’s world is American imperialism is to have only the most outdated “principles”—principles that, in the case of Syria, Rwanda, Bosnia, Kosovo, and even Libya, have left, or would have left, the most vulnerable and suffering without any recourse to safety and protection.

If the United States announced tomorrow morning that it would no longer use its military for anything but to defend the borders of the homeland, many would instinctively cheer, perhaps not quite realizing what this would mean in practice. But that is the conundrum the Left is now facing. A world without mass slaughter, of the sort of we are seeing every day in Syria, cannot ever come to be without American power. But perhaps this will prove one of the positive legacies of the Obama era: showing that the alternative of American disinterest and disengagement is not necessarily better. For those, though, that care about ideology—holding on to the idea that U.S. military force is somehow inherently bad—more than they care about actual human outcomes, the untenability of their position will persist. That, too, will be a tragedy, since at a time when many on the Right are turning jingoistic or isolationist, there is a need for voices that not just believe in U.S. power, but believe that that power—still, for now, preeminent—can be used for better, more moral ends.

Commentary

Is a better world possible without U.S. military force?

October 19, 2016