Since the early 1960s, Saudi Arabia has been one of the most stable and predictable players in the Middle East, writes Bruce Riedel. That all appears to be in doubt. Splintering the royal family is a dangerous approach. A dangerous region is getting more volatile. This piece originally appeared on The Daily Beast.

The Trump administration has tied the United States to the impetuous young crown prince of Saudi Arabia and seems to be quite oblivious to the dangers. But they are growing every day.

Saudi Arabia’s King Salman and his favorite son, Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman, have broken with the traditional patterns of consensual politics in the royal family, and the results are likely to be a much less stable kingdom with increasingly impulsive and erratic policies.

A purge is now under way that includes imprisonment of top princes (albeit in a former luxury hotel), the confiscation of assets, and at least two mysterious deaths.

“I have great confidence in King Salman and the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia,” President Donald Trump tweeted on Tuesday morning, “they know exactly what they are doing…” Then he went on, “…Some of those they are harshly treating have been ‘milking’ their country for years!”

….Some of those they are harshly treating have been “milking” their country for years!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) November 6, 2017

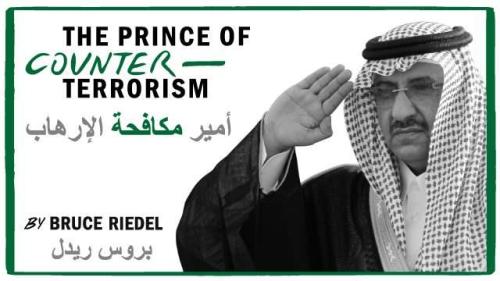

Earlier, the king sacked two sitting crown princes, Muqrin bin Abdelaziz and Muhammad bin Nayef, a very close ally of the United States in the fight against terrorism, to advance his young son’s prospects. These are unprecedented moves in Saudi history. And this weekend he sacked the commander of the Saudi Arabian National Guard (SANG), Prince Mutaib bin Abdullah.

The SANG is a 100,000 man praetorian guard that protects the royal family from coups and revolution. Mutaib was the favorite son of the late King Abdullah. His ouster alienates a powerful wing of the family and a large tribal alliance.

The king also appointed his 32-year-old son, known as MBS, to head a crackdown on corruption. At least 11 princes were detained along with dozens of former officials. Among those arrested is a senior official in the Bin Laden Group construction firm, the largest in the Middle East, and Prince Al Waleed bin Talal, a billionaire close to King Abdullah and a longtime promoter of reform in the kingdom. An earlier wave of arrests this summer targeted dissident intellectuals and clerics from the powerful Wahhabi establishment.

At least one prominent royal reportedly has died in mysterious circumstances. Prince Abdelaziz bin Fahd, the playboy favorite son of King Fahd, is rumored to have been shot while resisting arrest. He has been critical of the ouster of former Crown Prince Muhammad bin Nayef. Another prince died in a helicopter crash near the Yemeni border.

All of this suggests conspiracies and power plays far outside the bounds of normal Saudi politics.

The kingdom has always been a police state and an absolute monarchy married to a theocracy. But royal politics inside the family observed a certain decorum. If a prince or minister was removed he kept his honor and integrity, no one was humiliated. If a prince or princess misbehaved he or she was quietly detained, without any publicity, for private rehabilitation.

The firing of Muhammad bin Nayef instead was accompanied by rumors of drug addiction and he has been kept under house arrest since. The current wave of arrests has taken those detained to a former guest palace outside Riyadh where they are isolated from outsiders. Until Saturday, it was a hotel.

Powerful interest groups in the family have now seen their longstanding power centers stripped away. Their fortunes are being seized by the state, which is cash short due to low oil prices and wasteful spending. The young prince is making a lot of enemies.

Adding more drama to the game, the pro-Iranian Houthi rebels in Yemen fired a ballistic missile at Riyadh’s international airport on Saturday, which the Saudis claim they intercepted with an American made Patriot missile. This followed Houthi promises that all the capitals of the Saudi led coalition fighting them will now be targeted by missiles. Abu Dhabi may be next. With Iranian technicians and expertise helping the Houthis, that threat is real. In response the Royal Saudi Air Force is bombing Sanaa, the Yemeni capital, relentlessly.

The 30-month-old war is Muhammad bin Salman’s signature foreign policy. He promised a “decisive storm,” but he got a quagmire and the world’s biggest humanitarian catastrophe. The war costs billions that the Saudi economy cannot afford.

Since his trip to Riyadh last May, President Trump has wholeheartedly backed the king and his son. Over the concerns of the State Department and the US military, the White House has endorsed the Saudi-led effort to blockade Qatar. The blockade has been a failure so far and has probably destroyed the Gulf Cooperation Council, the regional alliance which the U.S. has backed since Ronald Reagan.

The administration has trumpeted its policy as securing tens of billions of dollars in arms sales. In fact very few have gone beyond the discussion phase. They are more statements of interest than contracts. It’s mostly fake news.

The president also wants the Saudis to put their oil firm ARAMCO on the New York Stock Exchange when it goes public for foreign investment next year. Many experts doubt that the Saudis will actually do so because it would require some transparency about how the company spends its proceeds, and it may be kept closed except to a handful of Chinese investors.

If it is put on the NYSE the Saudis will risk judicial action to seize the company’s assets under the Justice Against Sponsors of Terrorism law passed last year over a veto by President Barack Obama. The law allows suits against the Saudi government and individuals for alleged involvement in the 9/11 plot. Trump supported JASTA in the campaign, as did virtually every American politician especially in New York.

The king and his son have embraced the most virulent sectarianism in the modern kingdom’s history against Shia at home and abroad. The Saudis encouraged Lebanese Prime Minister Saed Hariri to quit his post, apparently hoping to isolate Hezbollah. Now the Saudis are saying they are at war with the group. Most likely the gambit will ricochet and benefit the Iranians and Hezbollah.

Since the early 1960s, Saudi Arabia has been one of the most stable and predictable players in the Middle East. Aside from some terrorist threats, usually quickly eradicated by Muhammad bin Nayef, it has been a safe place to travel and invest. That all appears to be in doubt. Splintering the royal family is a dangerous approach. Arresting and perhaps even killing political opponents is not likely to encourage investors. Fanning sectarian violence is bound to fuel turbulence. A dangerous region is getting more volatile.

Commentary

Trump’s bet on Saudis looks increasingly dangerous, and the $110 billion payoff? Unlikely.

November 7, 2017