After yet another round of negotiations on the Iranian nuclear issue this week in Vienna, Tehran is simultaneously reinforcing its red lines while raising expectations that a final agreement remains within reach. While these might sound like mixed messages, in fact they are part of a sophisticated, multi-prong strategy aimed at pressuring Washington and its negotiating partners to accede to Tehran’s stipulations for a deal.

Below, I have outlined the elements of Iran’s eleventh-hour approach, which has been remarkably effective in framing the final push toward a deal before the November 24th deadline. What remains uncertain still is whether it will succeed. The latest round of talks ended today amidst modestly upbeat statements from both sides. However, the frustration that has been expressed privately and the vague admonitions from U.S. officials in Vienna that “the Iranians have some fundamental decisions to make” — together with recent statements by Iranian negotiators about extending the deadline — underscores that a resolution to the nuclear crisis remains out of reach.

Hold Fast on Enrichment By Leveraging Domestic Opposition

Since the June 2013 election of Hassan Rouhani as Iran’s presidency, the Iranian leadership has struck divergent tones on the nuclear issue. Rouhani and his charismatic foreign minister, Mohammad Javad Zarif, have openly campaigned for a deal and advocated broader possibilities for U.S.-Iranian engagement, while Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, has consistently expressed skepticism that an agreement can be reached and has maintained his traditional full-throated hostility toward Washington.

These divisions within the elite are genuine; Iran has always been a highly factionalized polity, with intense ideological infighting over foreign policy as well as other affairs of state. And Khamenei openly derided Rouhani’s achievements as the country’s chief nuclear negotiator from 2003-2005. For that reason, analysts have importuned the West from the outset of his administration to “help Rouhani” persuade his hard-liners by offering generous terms for a deal. And Zarif and his colleagues have repeatedly raised the specter of Iran’s politics hardening once again if a deal is not reached.

Increasingly, however, Iranian officials have sought to deploy their internal differences to justify inflexibility on key terms. That tactic makes a virtue of one of Iran’s persistent vulnerabilities; the divisions within its ruling system have enabled an elaborate game of good-cop-bad-cop. That dynamic has increasingly dominated the negotiations since early July, when Khamenei articulated an ambitious bottom line on enrichment – raising the stakes on an issue that has long been the foremost point of contention in the talks. The sermon came only weeks before the initial deadline for a comprehensive deal, as Iranian negotiators were sitting with their American, Russian, Chinese and European counterparts in Vienna.

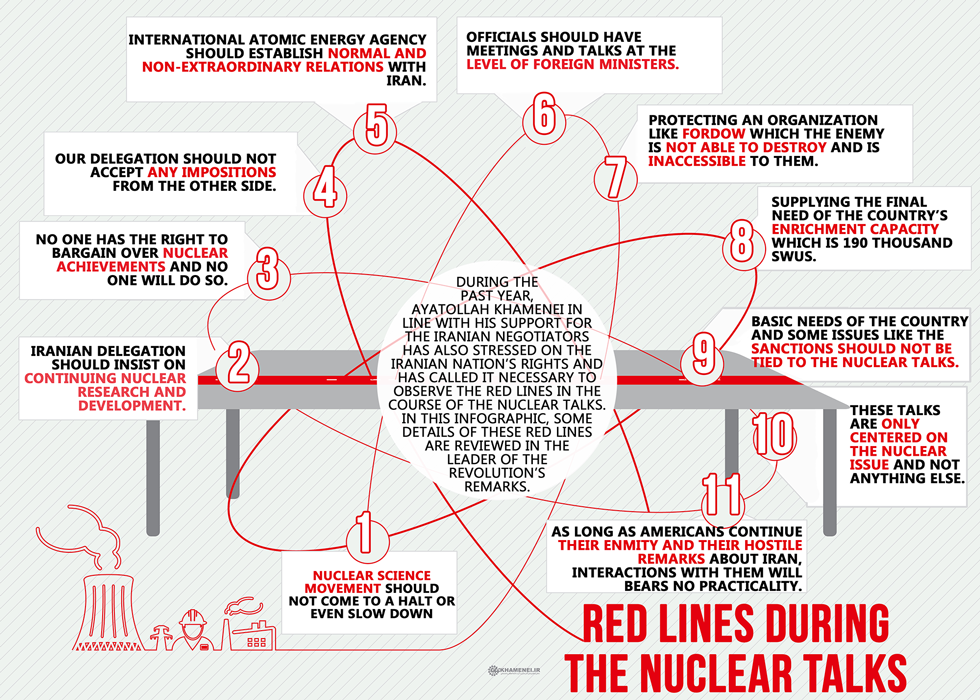

The latest salvo was the release of a new infographic, below, by the office of the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei via website and Twitter. The diagram aggregates various proclamations that Khamenei has issued regarding the nuclear talks over the past year to outline in no uncertain terms the regime’s “red lines” or requirements for an agreement. The information itself isn’t new, but the message is clear: Khamenei calls the shots, and the only way Iran will sign onto a comprehensive nuclear agreement is if it satisfies his maximalist requirements.

(From

https://twitter.com/khamenei_ir/status/521212555587383296

)

Many media reports have interpreted Khamenei’s interventions as an effort to box in his negotiators, a view that is apparently shared by at least some of the P5+1 governments. At the time, Reuters cited an unspecified Western intelligence analysis as declaring that Khamenei’s “remarks were aimed at severely curtailing his team’s room for maneuver, making it effectively impossible to bridge gaps with the stance of the (six powers)…In our assessment, Khamenei’s remarks were not coordinated with the Iranian negotiating team in Vienna at present, and were intended to cut off their ability to negotiate effectively.”

This is a reasonable interpretation, but ultimately there is no hard evidence that absent the Supreme Leader’s public rhetoric, Iran’s position on enrichment was particularly flexible. In fact, Rouhani has been explicit from the start of his presidency that he would not yield on the issue of enrichment, insisting instead that “(t)here are so many other ways to build international trust.” And in the days after Khamenei’s speech, Zarif proffered Iran’s first and only substantive proposal on the issue of enrichment, which included no reductions in enrichment capacity whatsoever, suggesting instead that the most he could do was to “try to work out an agreement where we would maintain our current levels” along with measures to reduce the applicability of the enriched uranium for weapons purposes.

This posture has not gone totally unnoticed; Brookings Foreign Policy Senior Fellow Robert Einhorn warned months ago that Iran’s position on enrichment could be “a showstopper” for the negotiating process. And the International Crisis Group has repeatedly pointed out that “Tehran’s general approach is to trade transparency for capacity: accepting more intrusive inspections in return for a higher enrichment capability and continuation of research and development.”

Still, the presumption that there are wide gaps between Iran’s hardliners and its official representatives on what constitutes acceptable concessions in a deal remains an article of faith, and a convenient one for a system interested in perpetuating the negotiating process. By wielding Khamenei’s intransigence on enrichment as an immovable object, Iranian negotiators can claim to be bargaining in good faith even as they reject any compromise on the core issue on the table. “We are ready to stay with the negotiations until the very last minute,” Zarif rhapsodized while in New York. “We are ready for a good deal, and we believe a good deal is in hand.” Left unsaid was the vast gulf between what Tehran considers a good deal, and what might be considered acceptable to its negotiating partners.

Capitalize on Shifting Priorities to Dilute Terms of the Deal

The Iranian approach also relies on the calculation that after more than a decade of frustrating talks and amidst a context of regional chaos, international resolve on the protracted, intractable nuclear crisis may be waning. “The world is tired and wants it to end, resolved through negotiations,” Rouhani asserted earlier this week. This alleged apathy toward the nuclear issue is exacerbated by the emergence of a more immediate and arguably more compelling threat emanating from the group known as the Islamic State (also referred to as ISIS or ISIL.) As I’ve argued previously, both Rouhani and Zarif focused their public remarks while in New York last month on the proposition that an expeditious nuclear bargain could be instrumental in securing Iranian assistance in the U.S.-led campaign to degrade ISIS.

The extension of the argument, as articulated by Zarif and others, is that the temptation of a deal — any deal — should be powerful enough to override any meticulousness on the details, particularly for an Obama administration that is struggling to develop an effective response to regional instability. The latest purveyor of this message is a group of renowned Iranian film directors who recently launched a savvy new social media campaign, No2NoDeal. Although the Foreign Ministry has denied reports in the Iranian press that this campaign was orchestrated by the government, the campaign’s moniker and its mantra is a word-for-word repetition of one of Zarif’s regular talking points and its advocacy is entirely directed at Western publics and, by extension, the P5+1 governments. The notion has taken hold with some audiences, including former British foreign secretary Jack Straw, who recently importuned that the P5+1 must accept “not to make the best the enemy of the good.”

Iranian officials see Western leniency in the nuclear talks as a fair price to be paid for extending the Islamic Republic’s proven capacity to shape outcomes in Iraq and Syria to the Obama administration’s newborn campaign against ISIS. As I wrote last month,

Once again, as in so many previous iterations of the U.S.-Iranian flirtation (Iran-contra, goodwill-begets-goodwill), a quid pro quo is being dangled before Washington; for the small price of nuclear concessions, Iranian assistance against ISIS can be bought. “If our interlocutors are also equally motivated and flexible, and we can overcome the problem and reach a longstanding agreement within the time remaining,” Rouhani cajoled in his UNGA speech, “then an entirely different environment will emerge for cooperation at regional and international levels, allowing for greater focus on some very important regional issues such as combating violence and extremism in the region.”

Tehran is eager to reinforce its bonafides in this effort — which explains the sudden proclivity of the previously reclusive Qasem Soleiman, commander of the Revolutionary Guards’ Qods Force, to indulge in battlefield selfies from the frontlines of the assault against ISIS in Iraq. “Iran is a very influential country in the region and can help in the fight against the ISIL (IS) terrorists,” a senior Iranian official told Reuters recently, adding, “but it is a two-way street. You give something, you take something.”

Depict Iran’s Rehabilitation as a Fait Accompli

The third aspect of the strategy is a skillful, and largely successful, campaign to redefine Iran’s image on the world stage in order to move beyond the nuclear standoff. The media blitz associated with Rouhani quickly began to erase Iran’s identification in the popular imagination with the noxious rhetoric of his predecessor, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, and the appalling repression that occurred in aftermath of the preceding presidential ballot. Instead, Rouhani and company have sought to persuade the world that the era of Iranian isolation has now passed, the nuclear impasse is — well, effectively — relegated to history, and that business as usual can resume immediately.

This is why Rouhani told a New York audience that the Obama administration should “leave behind (this) insignificant issue,” and why he proclaimed on state television earlier this week that despite widespread pessimism about the status of talks, “we believe that the two sides will certainly reach a win-win agreement.” Others in the Iranian establishment have made similarly dismissive noises about the outstanding issues; Ali Larijani, the current speaker of the parliament and former nuclear negotiator, recently sniffed that the enrichment impasse is a “trivial matter.”

Ironically, Rouhani’s declare-victory-and-go-home stance is somewhat reminiscent of his predecessor’s approach; Ahmadinejad repeatedly proclaimed that Iran was already a “nuclear state” in what was interpreted by some analysts as a pretense for assuaging Iran’s national pride while testing the possibilities for an exit strategy from the impasse.

Rouhani’s motives are similarly elastic. He has invested heavily in seeking a deal to end the nuclear stalemate, but he also insists that Iran must not “not sit idly to see whether the foreign parties will respond positively or negatively.” Instead, he has sought to stabilize the country’s economy and expand its diplomatic horizons in a fashion intended to elevate Iran’s prospects irrespective of whether the nuclear issue is ever resolved.

Enhancing Iran’s economic prospects represents a fundamental driver of this aspect of the nuclear strategy. Rouhani has asserted that “the sanctions regime has been broken.” While this is patently false, Tehran can trumpet its improved policies for a preliminary turnaround as well as minor evidence of sanctions attrition, including judicial reversals of selective European designations and indications of revived European interest in Iran’s energy sector. Even today, London is the scene of an industry conference hyping the trade and investment possibilities in Iran.

Begin to Play the Blame Game

The fourth essential element of Iran’s late-inning strategy is more forceful efforts to ascribe responsibility for the continuing difficulties in achieving a deal to Washington. In Tehran’s telling, the Obama administration is the unreasonable party, insisting on “excessive demands” while Iranian negotiators have exhibited only generosity and forbearance in defending Iran’s “rights.” Throughout their recent visits to New York, both Rouhani and Zarif insisted that Iran has fulfilled its commitments under the Joint Plan of Action to the letter.

By contrast, Zarif repeatedly criticized Washington for what he alleges are departures from the provisions of the interim accord signed last November. “There is no international mechanism to measure how the United States has lived up to its commitment, if there were, I’m sure the United States would have gotten a failing score.” His complaint appears to derive from Washington’s ongoing implementation of existing sanctions, although enforcement is not prohibited by the JPOA and Iran’s negotiators plainly understood it would continue during this period.

More broadly, Zarif has frequently attributed the lack of progress in the nuclear talks to American caprice, contending that “the United States is obsessed with sanctions.” He blithely told another interviewer that Washington is the obstacle to an agreement and that Iran has articulated very modest requirements. “So there is a deal at hand. Within reach,” Zarif declared, adding “all that the United States needs to do is to get an agreement that can lead to the removal of sanctions. There is nothing else that we’re asking the U.S. to do. We are not asking for security guarantees, we are not asking for any money, we are not asking the United States to do anything — simply to remove the sanctions.”

In an interview with NPR’s Steve Inskeep, he asserted that the difficulty in achieving a comprehensive agreement “(t)he fact that we’re not close [to a deal] means that the United States and some of its Western allies are pushing for arbitrary limitations which have no bearing whatsoever on whether Iran can produce a nuclear weapon or not.”

These messages are amplified by more strident Iranian officials, including Ayatollah Khamenei in his role as head of state. In an August address to the country’s Foreign Affairs ministry, Khamenei expressed bitterness about the talks, noting that “the Americans’ tone also became harsher and more insulting and they expressed more unreasonable expectations during negotiations and in public podiums…Not only did the Americans not decrease enmities, but they also increased sanctions.” The bottom line for Iran’s ultimate decision maker? The nuclear talks “are not helpful at all” and “establishing relations and speaking to the Americans will not have any effect on reducing their enmity.”

For their part, U.S. officials have remained profoundly restrained in their public statements, insisting that they will not negotiate in public and simultaneously trying to avoid any rhetoric that would further complicate the prospects for a resolution. They also have a wider array of audiences to consider, including negotiating partners with a diverse interests and domestic rivals as well as regional allies that fiercely oppose the prospective terms of a nuclear deal. As a result, Washington has slowly lost its advantage in shaping the public narrative on the negotiations, despite unparalleled capabilities for disseminating its messages.

If, as expected, negotiators are unable to produce an agreement by November 24, the blame game may be the most important part of Tehran’s nuclear strategy, because it shapes the alternatives available to each side. Depicting American obstructionism as the cause of the talks’ demise will facilitate Iran’s acknowledged Plan B — an end-run around sanctions and an attempted breakout of the economic pressure and international isolation that helped generate the conditions for constructive negotiations in the first place.

Will Iran’s Strategy Succeed?

The Iranian strategy appears to be working – to a point. Iranian brinkmanship has succeeded in redressing the inevitable power imbalance between the isolated Islamic Republic and the powerhouse coalition comprised of world powers that already slashed Iran’s oil exports in half. By sticking to its guns, Tehran has gone from supplicant to sought-after in the talks, with Washington and its allies scrambling to devise formulas that might meet the supreme leader’s imperious mandates.

Still, it seems unlikely to me that Washington will acquiesce to Iran’s obstinacy on enrichment. The Obama administration has already extended major concessions to Tehran in devising a formula that Tehran could claim acknowledged its nuclear rights and in backing away from previous American insistence on a suspension or end to all enrichment on Iranian soil. Any deal that fails to redress the breakout timeline would gainsay a decade of efforts to deter Iran from nuclear weapons capability, as well as the strong preferences of America’s regional allies.

And more importantly, I think the presumption that the Obama administration is so desperate for a foreign policy victory, so feeble in its assertion of American interests and the security of our allies, or so eager for Iranian cooperation on other regional challenges that it will accept a hollow deal represents a profound misinterpretation of this administration’s foreign policy and the capabilities of the United States.

For that reason, I believe that Tehran’s four-point hedging strategy is a dangerous bluff, and one that will ultimately fail. I suspect that will not prove the end of diplomacy with Iran, but neither will it facilitate the end of Iran’s self-imposed forfeiture of its rightful place in the world. As a senior U.S. official said — not for the first time — yesterday in Vienna, “the question remains whether Iran’s leaders can and will seize this opportunity.” The cost of another failure is high, and the durability of the multilateral sanctions regime and the long reach of U.S. unilateral measures means that it will be paid entirely by the Iranian people.

Commentary

Reading Between the Red Lines: An Anatomy of Iran’s Eleventh-Hour Nuclear Negotiating Strategy

October 16, 2014