The report last week from the U.S. Census Bureau confirmed what many experts and advocates have worried about over the past two years: Despite achieving an accurate overall estimate of the population, the 2020 census suffered from significant undercounts of racial and ethnic minorities. More specifically, there was a 3.30% undercount of the Black population, 4.99% undercount of the Latino population, and 5.64% undercount for American Indian/Alaskan Native populations who live on reservations or tribal lands. The Latino undercount in 2020 is three times the 1.54% undercount in 2010, a statistically significant difference. Given the significant consequences associated with the population numbers generated by the census, civil rights leaders are calling for changes to be made to the process—one that consistently diminishes the political influence of diverse communities who are hard to reach.

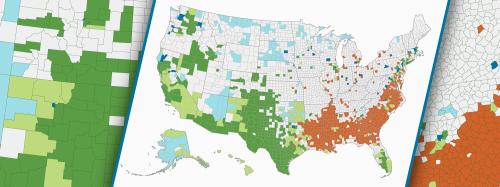

With redistricting wrapping up across the country, the impact of undercounts on these communities’ ability to elect leaders to promote their interests is already being felt. As we know, states base decisions on maps defining political districts on the census population estimates, with creation of districts where communities of interest (such as racial and ethnic minorities) have influence over the election outcomes in their districts. The poor performance of the 2020 redistricting process has undoubtedly cost communities of color political representation over the next decade.

The Many Benefits of Minority Representation

The value of racial and ethnic diversity within a wide range of institutions, from Congress to the National Football League, have been well documented following the summer of racial reckoning in 2020. What has often been at issue is descriptive representation, which refers to a match between the elected official and their constituency based on descriptive attributes such as race, ethnicity and/or gender.

Here are three ways in which descriptive representation is important to the healthy functioning of American democracy:

- Because diverse representatives understand the needs of their diverse constituents, public policies tend to be more aligned with the needs of those communities. It is this relationship between descriptive and substantive representation that has so many worried about implications of the census undercount on the ability of diverse constituencies to influence election outcomes over the next decade.

- Descriptive representation also leads to increased political participation among racial and ethnic minorities, with higher turnout among both Latino and African American eligible voters when they live in states with higher levels of descriptive representation in their state legislature. The presence of descriptive representation also leads to a greater sense of ethnic identity and perceptions of commonality among Latinos.

- Among the benefits associated with descriptive representation is the positive correlation it has with trust in government, whether through forging bonds between legislators and their constituents and/or an enhanced feeling of inclusion among diverse constituencies. This is an important normative outcome given the long histories of political marginalization these groups have faced in the United States and the dangerously low levels of trust in political institutions right now.

The Value of Descriptive Representation Magnified During the Pandemic

The importance of descriptive representation became evident during the pandemic when the need for trusted voices to disseminate information and help encourage compliance with policies aimed at reducing the spread of the virus. The AARC/Commonwealth National Vaccine Poll included tests of the relative effectiveness of several sources of COVID-19 vaccination information. Respondents were asked to report on a scale of 0 (no trust at all) to 10 (totally trust), how much they trusted a wide range of potential messengers if they participated in a campaign to encourage Americans to get the COVID-19 vaccine.

Although members of Congress trailed medical professionals by a significant margin among trusted messengers, elected officials were viewed to be highly effective by 19% of all Americans in the sample. This is higher than all celebrity messengers tested in the survey. Reinforcing the importance of diversity across elected offices, when asked to rate elected officials from their own respective racial or ethnic group, descriptive representatives were rated more positively than a respondent’s own member of Congress (23% highly effective). Descriptive representatives were particularly effective messengers for African American and Asian American/Pacific Islander Americans.

Descriptive representation is particularly important to Native Americans, the racial and ethnic group who often are found to have low levels of trust in non-tribal government and elections, with this lack of trust having a marked impact on turnout. Tribal leaders have been found to be highly trusted messengers for Native Americans, with tribal government and tribal leaders both being viewed as effective messengers among Native American respondents asked to evaluate messengers for COVID-19 vaccination. Native American representatives played a key role during the pandemic by disseminating important public health and vaccination information to their constituents and Native communities more broadly. Native American representatives also took important steps to advocate for increased government relief and response from the federal government for their communities.

What Can be Done to Address the Undercount?

With most states already finished redrawing redistricting maps, the damage caused by flawed counts for racial and ethnic minorities has already been done. However, there may be an opportunity for the adjusted numbers to be used in jurisdictions where lawsuits challenging states with gerrymandering are taking place. Researchers arguing for expanded influence in districts for communities of interest in these cases should be able to reference the adjusted numbers in their maps, and courts should consider the inaccurate counts when possible in their decisions. While limited to a relatively small number of locations across the country, this would provide some sense of justice for these communities who have had their political influence undercut by the inaccurate count.

Thinking longer term, Congress should strongly consider reforming the decennial process to ensure that there are protections in place to prevent presidential administrations from weaponizing the census count for political purposes. The political manipulation of the census by the Trump administration should generate the political will needed to reinforce the independence and integrity of the U.S. Census Bureau. There is also an obvious need to improve the decennial count so we do not continue to see significant undercounts of hard to reach populations. With nearly 10 years before the next census, there is time to get this done.

Finally, I agree with other experts who have called on state legislators to use the adjusted estimates as they set policy priorities for their states. The importance of census population figures to policymaking and revenue distribution are huge. The inaccuracy of the 2020 count has already done significant harm to Latino, Black, and Native American communities across the country. All steps that can be taken to minimize this injustice should be seriously considered.

Commentary

Why census undercounts are problematic for political representation

March 28, 2022