The most profound change in American politics today and in the years to come will result from a massive movement of women into the Democratic Party. As this realignment takes place Hillary Clinton may well go down in history as this century’s equivalent of Al Smith. Al Smith was the Democratic nominee for president in 1928 and the first Roman Catholic ever nominated by a major political party. Although he lost the election, his campaign presaged the movement of Catholics into the Democratic Party in 1932 when Franklin Roosevelt won the Democratic nomination and the presidency. Smith’s race was initially considered a failure, as was Hillary Clinton’s. But her defeat has set off a chain reaction likely to lead to a realignment of party coalitions and relative political strength in 2020 as sweeping as FDR’s victory in 1932.

As far back as the Reagan presidency, there has been a gender gap in American partisanship with women tilting toward the Democratic Party and men toward the GOP. But the overwhelming change in political party demographics since Trump’s victory in 2016 is the culmination of a long-term movement in party identification and voting behavior among women. With the election of Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton, what had been a modest gap of variable proportions has turned into a chasm so wide no Republican presidential candidate will be able to cross it for years to come.

In 2012, according to CNN exit polls, women preferred Barack Obama over Mitt Romney by 11 percentage points (55% to 44%). In 2016, Clinton led Trump by 13 points (54% to 41%), but in the 2018 midterm elections women opted for Democratic rather than Republican congressional candidates by 19 points (59% to 40%). More important for the long term, the Democratic margin over the Republicans in party identification grew from six points in 1994 (48% to 42%) to nearly twenty in 2017 (56% to 37%).

Even though the trend toward the Democratic Party among women is most pronounced among college graduates, it is also visible both among those who went to college but didn’t graduate and those with only a high school education. Among voters of each and every racial background and ethnicity, women have increased their identification with the Democratic Party. The effect is most pronounced among America’s younger generations—Plurals (the best name for the generation after Millennials) and Millennials—but a rise in Democratic affiliation, albeit a smaller one, has also occurred among Gen X’ers, Boomers and even Silents, America’s oldest adult generation. The trend may be larger or smaller in each of these categories but always in the same direction.

This increasing attachment to the Democratic Party reflects a deep-seated belief by women that most Republican men don’t see the world the way they do. For example, a 2019 Pew Research survey indicated that 69% of all women and 83% of women who identify with or lean toward the Democratic Party believe that “significant obstacles still make it harder for women to get ahead than men.” A solid majority (69%) of male Democratic identifiers concur. By contrast, 81% of men identifying with or leaning toward the GOP perceive that the “obstacles that once made it harder for women to get ahead are largely gone.” More recently, a January, 2020 poll found a 19-percentage-point gender gap in President Trump’s approval rating. Only 38% of women approved of the job Trump was doing, compared to 57% of men. This nineteen-point gap was 8 points higher than the 11-point gap as measured in 2016 general election exit polls.

The gender realignment of American politics is the biggest change in party affiliation since the movement by loyal Democratic voters to the GOP in the “solid South,” which realigned regional political coalitions into the partisan dynamics we are familiar with today. In 1976, Jimmy Carter won all of the former Confederate states except for Virginia as well as the border states of Kentucky, Missouri, and West Virginia. By 2000, Al Gore’s presidential campaign lost all of them, including his home state of Tennessee. It took a while for this transformation to occur in the South—emerging first in urban and suburban areas and only at the end becoming entrenched in the more rural parts of the region, where it is strongest today. But with the speed of news and information in an era dominated by social media and cable news, the trend is likely to spread further and faster this time, certainly soon enough to greatly influence the outcome of the 2020 presidential election.

The shocking defeat of Hillary Clinton at the hands of the overtly misogynistic Donald Trump put the existing trend into hyper-drive. It broke upon the national scene in cities across the country with previously unseen numbers starting with the Women’s March the day after Trump’s inauguration. Then it surprised almost everyone when it led to the election of a Democrat to the Senate in Alabama in a December 2017 special election. That result, which stemmed in significant degree from defections of Republican women in the state’s cities, suburbs and college campuses as well as a massive turnout of African-Americans, was quickly dismissed as an anomaly since the Republicans had nominated a sexual predator and pedophile as their candidate.

But no one could ignore the size and national impact the same shift had on the outcome of the midterm elections in November 2018. Exit polls that year showed women favored the Democratic candidate for Congress by 19 percentage points (59% to 40%), while men favored the Republican candidate by four points (51% to 47%). The resulting gender gap of 23 points was the widest one in the last twenty years.

Still, most commentators point only to the suburbs as the place where the shift in the women’s vote is happening. There is certainly some validity to that perspective. For example, in suburban Bucks, Chester, and Delaware Counties, Pennsylvania, just outside of Philadelphia, the Democrats took over the Boards of Commissioners in 2019—the latter two for the first time since before the Civil War. Nationally, the University of Chicago Harris/AP-NORC Poll in January 2019 showed that the suburban vote had shifted from an even split in party preference in 2016 to a 7-point Democratic advantage, 46-39, in just two years. And a January 2020 NBC-Wall Street Journal poll indicated that suburban women identify as Democrats over Republicans 47% to 34%, up from 43% to 40% in 2010.

The idea that educated suburban women have shifted their voting preferences from Republican to Democrat is not wrong, but it doesn’t reflect the full extent of the change that is happening in plain sight in American politics. In the past two years alone, women’s representation in state legislatures has increased from 25.4 percent to 28.9 percent of all state legislative seats. That year, Nevada, both of whose U.S. Senators are women, became the first majority female legislature. Colorado also came close to gender parity, with a legislature that is 47 percent female. The National Women’s Law Center (NWLC) found that women state legislators introduced and enacted more legislation than men over the two most recent legislative sessions. Virginia became a thoroughly blue state in 2019 as women voters finished the state legislative revolution they had started in 2017. To complete the picture, a woman is now governor of mostly rural Kansas.

The shift is far from over. In other parts of society, most notably the famous #MeToo movement, women’s opposition to sexual harassment has been responsible for the downfall of many powerful men. Witnessing the type of change their numbers have brought in other parts of society in the last few years has only further whetted women’s appetite for using their political power to wipe out the remaining vestiges of male privilege and the type of behavior it condones. With organizations such as Emily’s List and The Women’s Campaign Fund providing a more robust infrastructure for female candidates, it won’t be long before the political preferences of women voters determine the winners and losers in American politics.

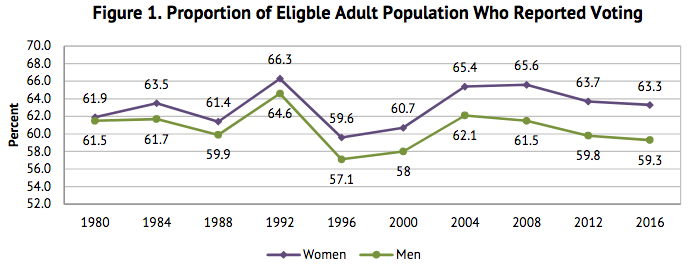

Democrats already enjoy a built-in advantage in the demographic trends that are continuing to make the American electorate more diverse, more educated, younger, and more urban. However, when a group that represents half or more of the electorate, as women do, shifts even slightly in party preference, it has a lot more impact than when a relatively smaller demographic group realigns by larger percentages. Since 1980 when men and women voted in about equal numbers, women have consistently outvoted men as the chart below indicates. Women turned out at greater rates than men in the 2018 midterms among every age group except those over 65. The trend continued in the first two Democratic nominating contests in 2020 with women making up 58% of Iowa caucus participants and 57% of voters in the Democratic primary in New Hampshire.

The full effect of gender realignment may not be fully felt in the rurally skewed electoral college in 2020, but it certainly increases the odds that this year whoever the Democrats nominate will win not only the popular vote but the presidency as well.

Commentary

The future is female: How the growing political power of women will remake American politics

February 19, 2020