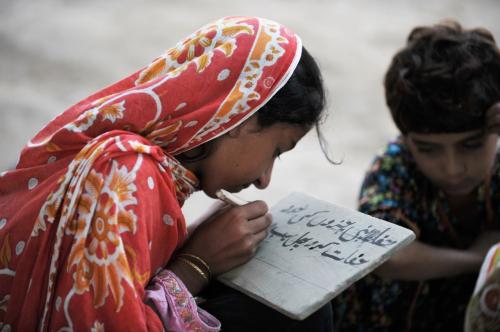

Pakistan’s rural population is disproportionately affected by the low quality of the public education system, with girls and young women the most underserved. Of the 20 million children not going to school, 4 out of 5 live in rural parts of the country, and of those, 60 percent are girls. Education exclusion for girls is compounded when location disadvantage intersects with income, spoken language, religion, caste/kin, and parents’ education. The problem of schools not reaching rural girls living in poverty demands a holistic examination, capturing the nuances that arise due to the economic and social contexts. If inequalities surrounding schools and children are not considered in policy responses, they permeate into classrooms and pathways beyond education, rather than generating new opportunities.

Sindh, the second-most populated province in Pakistan, has the largest disparity between urban and rural areas and the lowest school participation rates for rural girls in the country, making it a critical area to address social inequities if the country is to make significant progress in improving overall education outcomes. However, education inequity is expected to further increase due to climate-intensified floods that hit large swathes of rural Sindh in August 2022, which in addition to interrupting access to school and learning, also worsened poverty, nutrition, and health indicators. To arrest these trends that have the potential to further amplify exclusion from schooling, efforts to rehabilitate communities and schools must consider both the urgent and long-term needs and aspirations of children in rural areas, so they are able to (re)enter, learn, and thrive in schools.

As a 2022 Echidna Global Scholar, I conducted research to understand the economic and social context of rural communities in Sindh and the education needs and aspirations of families and children. Over the summer of 2022, I visited eight settlements in four districts across Sindh, so as not to fall into the traditional trap of considering rural communities a homogenous group. Based on prior experiences of working with populations with limited exposure to schooling, I used a mix of visual-based activities and structured focus group discussions. My research assistant and I worked with children, mothers, and fathers to design an ideal school. Based on photographs we provided, they chose the type of school building, means to get to school, teacher actions in the classroom, learning activities for children, and ancillary services they would like in their school; the design of this ideal school by children and parents informed both the findings and policy recommendations.

How are the needs and aspiration of girls in rural Sindh, Pakistan not being met?

We found that parents valued education and believed that it could improve their children’s futures; they wanted education to lead to better moral upbringing, jobs (more so in the case of sons), and home environments (more so in the case of daughters). While there were some exceptions, parents generally expected their daughters to receive fewer years of schooling compared to their sons; this was especially true in communities with limited access to schools beyond the primary grades, where means to get to secondary schools were seen as unsafe, especially, for girls once they reach puberty.

Gender factored into parents’ decisionmaking about enrollment into primary grades, too, especially when nearby schools had limited spots and families struggled with multiple demands on limited financial resources due to systemic poverty. Only half of the settlements surveyed had functional school buildings and all of these were overcrowded. This is unsurprising, considering that more than three-fourths of primary public schools in rural Sindh have two rooms or less and most were built more than two decades ago when the population was much lower. With capacity constraints in the local primary school, parents often chose to enroll sons over daughters, with greater likelihood of sons able to continue schooling beyond primary. In cases of high poverty, girls were pulled into household chores and child care responsibilities as young as six years old—much earlier than boys—which also acted as a barrier for school enrollment and learning.

For children who were enrolled in schools, parents reported that learning outcomes were affected by classroom design and practices. This aligns with an annual ASER report on quality of Pakistan’s education system, which reports that by grade five, only 2 out of 5 children can read a story and 3 out of 10 can solve division questions in rural Sindh. Parents highlighted that classroom teaching practices were weak in the absence of requisite pedagogical support to teachers, including but not limited to training for multi-grade, multi-lingual classrooms and classroom management for overcrowded rooms.

In-school experiences were also weighed down by limitations of the formal education system, which does not adequately represent rural realities, the interests of children and their families, or local knowledge. Parents did not look to school-based education to prepare children for rural professions like farming or livestock management. It was more common for a community’s highly educated men to move out of the settlement, while in the case of women—even if they engaged in home-based or other jobs—they continued to be held responsible for household chores and child care, putting an inordinate burden on them. The current educational model in rural communities is not linked with improving lives in rural communities.

Recommendations

Given that education policy to date has been largely ineffective for rural settlements in Sindh and has excluded millions of children, the space is ripe with possibility for fostering opportunities for inclusion and belonging, allowing children and young adults to individually and collectively shape their own lives and those of their communities. But for this to happen, education policy must respond holistically, from a systemic and contextual lens.

1. Adopt a multi-sectoral approach for inclusion of all children

Sindh needs a welfare-based approach that supports children to overcome poverty and enroll and continue with school. For instance, registration and tracking of births for timely enrollment, in-school feeding programs, and transportation for younger children and older girls are interventions that would require coordination with other sectors.

2. Design more inclusive education

Design of classroom experiences and learning materials must allow for contextualization, build a connection with rural realities, and create space for children to aspire to pathways that may not be traditionally associated with formal education.

3. Augment teacher training for inclusivity

Teachers need ongoing support to create inclusive classroom experiences for all children that promote their learning and well-being, prepare them to navigating pathways beyond education, and question root causes of exclusion.

I will present the findings from my policy brief and share more detailed recommendations at the research and policy symposium on gender equality in and through education on “De/reconstructing education as a space for transformative belonging and agency” beginning December 5; please register for my virtual workshop on December 7 for a deep dive on policy design to support meaningful learning experiences and aspirations for underserved children in rural Pakistan.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

How can a holistic education policy help bridge the opportunity gap for girls in rural Pakistan?

November 30, 2022