It goes without saying that 2020 brought a lot of challenges and changes to the world. These challenges wrought by COVID-19 have been felt most acutely by some of the most vulnerable populations in the world. At the peak of the pandemic, approximately 1.6 billion children—90 percent of the student population globally—were out of school. One estimate suggests that a school closure for a third of the year results in an average of 1.03 years of learning loss for a third grade student. In addition, the number of employed persons and hours worked declined steeply across countries, ranging from a staggering 46 percent decline in hours worked in Mexico to a still high rate of 10 percent fewer hours worked in Australia. Moreover, COVID-19 has contributed to the worsening of gender poverty gaps, as women have largely experienced the burden of unpaid care and domestic work while quarantine measures have closed schools and kept people at home.

Social and development impact bond projects and related outcomes funds, which often target the needs of these vulnerable populations, faced the same challenges as other social services in meeting the incredible increased levels of need. In theory, however, the flexibility of impact bonds—with a focus on outcomes rather than specific inputs or activities—is aimed at providing flexibility in such situations.

Brookings research on the impacts of COVID-19

Our team at Brookings spent much of 2020 analyzing this theory. At the end of May, we published a policy brief examining the early effects of the crisis on projects supported by impact bonds. In interviews with stakeholders from 20 impact bonds from around the world, we overall found that the impact bond structure seemed to provide room to adjust course, as well as a strong framework for collaboration and problem-solving in the wake of the crisis. Some stakeholders noted, however, that the contractual agreements around outcome achievement and payments did cause some challenges.

We also had the opportunity to engage with key actors in the education impact bond space through a variety of media platforms. A Brookings Cafeteria Podcast episode featuring Jaime Saavedra, director of the Education Global Practice at the World Bank, focused on the potential role for impact bonds for education in the developing world, particularly in light of the pandemic. In response to a request related to the Quality Education India Development Impact Bond (QEI DIB), we organized a webinar bringing together the service providers, along with experts in crisis response in education from around the globe. And in another India and education-focused event, we contributed learnings from our research, together with other experts, using a variety of innovative financing tools to ensure that education reaches disadvantaged populations.

The impact bonds market: 10 years in

While much of the world’s focus was on the pandemic, March 2020 also marked the 10-year anniversary of the first impact bond. Throughout the month of September, we evaluated evidence across five different dimensions of success related to impact bonds in a series of five policy briefs.

Briefs 1 and 2: What is the size and scope of the impact bonds market, and are impact bonds reaching the intended populations?

The first two briefs examine the impact bond landscape over the first decade of their use. The first brief considers where (Figure 1) and in what sectors the most impact bonds have been contracted, and factors contributing to growth in these areas. The second brief examines the impact bond beneficiaries, as well as design elements to ensure that perverse incentives are avoided, and whether services are received by those most in need.

Figure 1. Impact bond global landscape map

Please see our current monthly snapshot for more information on the global landscape of over 200 impact bonds.

Brief 3: Are impact bonds delivering outcomes and paying out returns?

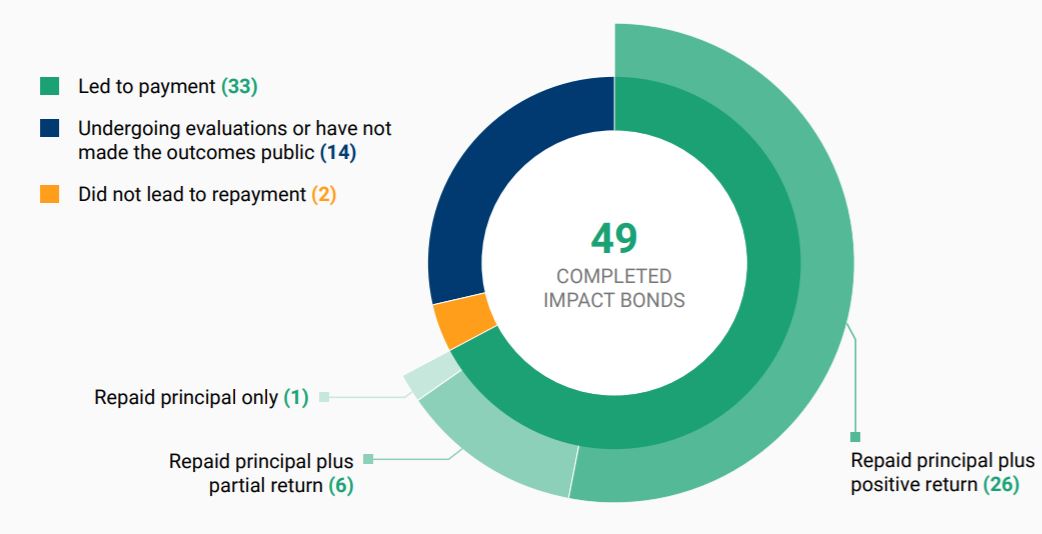

The third brief in the series examines the outcomes achieved thus far, primarily for completed impact bonds (49 as of publication cutoff). We found that investor returns range from around 1 percent to 20 percent of the original investment, with an average potential return of $2.5 million. Additionally, outcomes were achieved and investors were repaid (in most cases with returns) for all but two impact bond projects (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Impact bond repayment

While this evidence suggests, anecdotally, that impact bond projects have been successful at achieving outcomes, it is not actually possible to attribute this achievement to the impact bond mechanism itself without counterfactual evidence as to whether they would have been achieved through another mechanism.

Brief 4: Do impact bonds affect the ecosystem of social services delivery and financing?

The fourth brief in the series considers the broader ecosystems of social services delivery and financing, and to what extent impact bonds have shaken up and supported changes within these ecosystems. We examine this through the lens of the “10 common claims” about impact bonds, initially posited in our 2015 report and later revised in a 2017 report. We consider whether impact bonds:

- build a culture of monitoring and evaluation

- drive performance management

- foster innovation in delivery

- crowd in private capital

- reduce government risk

- incentivize collaboration

- sustain impact

Brief 5: Do the benefits of impact bonds outweigh the costs?

The fifth brief in the series considers perhaps the most important question when evaluating the success of impact bonds: Are they an efficient means of contracting social services, considering both the costs and the benefits? Since there is not much data on the costs of many social services—much less the costs of impact bonds specifically—and the benefits are difficult to measure, this brief explores some theoretical assumptions and posits a framework for future empirical research on this topic. Additionally, we explore how costs are decreasing with the first 10 years of impact bond experience now in tow.

What’s next?

While the end of 2020 brought good news with the start of vaccine distribution, the impacts of the crisis will continue well into 2021 and beyond, especially for many of the world’s most vulnerable populations. As such, we will continue to research the effects of COVID-19 to understand its holistic impact, as well as the use of impact bonds as a tool to build back better after the crisis, and we expect to publish more on this in the coming months.

We will also continue to follow closely impact bonds in the education sector. The QEI DIB—one of three education impact bonds contracted in developing countries—achieved impressive results after the second year, as we explored in a blog and webinar toward the end of last year. We noted that the big challenge for QEI, like for the education sector as a whole, will be how to overcome the learning losses and large-scale challenges of the COVID-19 crisis.

2020 also marked the conclusion of the Impact Bond Innovation Fund (IBIF), which provided early childhood development (ECD) services in impoverished neighborhoods outside of Cape Town, South Africa. With outcome funding coming from the Department of Social Development, this impact bond is one of only a handful where a developing country government provides outcome funding. We look forward to following what happens for the delivery of ECD in this region after the conclusion of the impact bond, particularly considering the expected negative impacts of the pandemic on child development and learning.

Also, in the education sector, the Education Outcomes Fund (EOF) launched calls for proposals in 2020 for its first two programs that will strengthen education systems in Ghana and Sierra Leone, with an aim to reach approximately 1,100 primary schools. A total of $45 million in outcomes funding is being committed to these programs by their respective governments and other donors. An interesting development is the shift of EOF from an independent entity to becoming a trust fund hosted at UNICEF, and, in the case of Ghana, donor funds are being managed by GPRBA at the World Bank (with the outcomes contracts issued by the government of Ghana). Although it remains to be seen, this development could lead to a more institutionalized set-up of the outcomes fund which could increase sustainability of the model.

Finally, as the impact bond market has grown over the past 10 years, so too has the variance in deal structures that fall under the outcome-based financing umbrella. In the coming year, we look forward to further exploring and fleshing out the boundaries around the “impact bond” definition, and why some variants in deal structure, such as the Haryana Early Literacy Outcomes Project, do not meet the definition of an impact bond for inclusion in our global database but still would be considered a form of outcome-based financing. These and other developments in the impact bonds market—many of which seek to improve efficiencies and increase scale—raise thought-provoking issues that we are excited to explore in 2021 and beyond.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

What a year: A review of the global impact bonds market in 2020

January 7, 2021