Almost every state with a public pre-K program uses a mixed-delivery approach, with some classrooms in public schools and others in community-based organizations (CBOs). It is easy to see why this approach is popular. Parents get more choices, localities can serve more children by partnering with existing pre-K providers, and public funding helps to stabilize much more expensive, harder-to-find infant and toddler childcare offered by CBOs.

Despite this seeming win-win, experts have long raised concerns about how structural differences between these settings may disadvantage CBOs relative to public school programs. For example, administrators and teachers in many CBO settings receive substantially lower compensation—fueling turnover and undermining quality improvement efforts—and are less likely to be unionized than their public school-based counterparts. The limited research we have suggests children in CBOs in some of these systems are more likely to be from marginalized groups and make fewer gains in pre-K than their public school peers.

As the country emerges from the pandemic, states and localities are making critical decisions about how to spend their remaining federal COVID-19 relief funds, and policymakers are determining the best bets for strengthening early care and education systems. Learning from pre-pandemic inequities within pre-K systems can help guide these decisions and build stronger and more equitable mixed-delivery pre-K programs.

In a new working paper, we use data from five large-scale, mixed-delivery pre-K systems that have taken explicit steps to improve equity across public school and CBO settings (Boston, New York City, Seattle, New Jersey, and West Virginia). New Jersey and West Virginia are some of the longest-running state-funded pre-K programs in the country, at 24 and 29 years in operation, respectively. Boston’s program began in 2005, while NYC and Seattle are among the newer crop of city-funded programs established within the last eight years. All five of these localities implemented largely the same program standards in both public school and CBO programs. For example, all required lead teachers in both settings to have at least a BA, and New Jersey, Seattle, and Boston paid teachers the same in both CBOs and public schools (and New York City did so in the years after data in our study were collected).

Our total study sample included nearly 4,000 children and 255 pre-K programs. About 60% of these children and programs were in public schools, while the others were in CBOs. Within each system we examined how child and teacher demographic characteristics, classroom learning experiences, and gains in children’s academic skills differed by setting. Consistent with longstanding concerns, where we found differences, they tended to favor public schools.

Comparing pre-K programs in public schools and CBOs

Some of the key differences we found across the five localities concerned who was where. Children in CBOs were taught by less educated teachers in all localities but NJ. For example, teachers with master’s degrees were more likely to work in public school than CBO settings in four of the five localities with the size of the difference ranging from eight (WV) to 51 (Seattle) percentage points. We also observed some notable differences in program delivery across settings. Despite similar class size and teacher-student ratios, we found a pattern in which public school classrooms were rated as having higher-quality teacher practices and classroom interactions on most comparisons. To be clear, the evidence on the importance of these factors in predicting gains in child outcomes is mixed, but they contribute to a fairly consistent picture of inequities between CBOs and public schools.

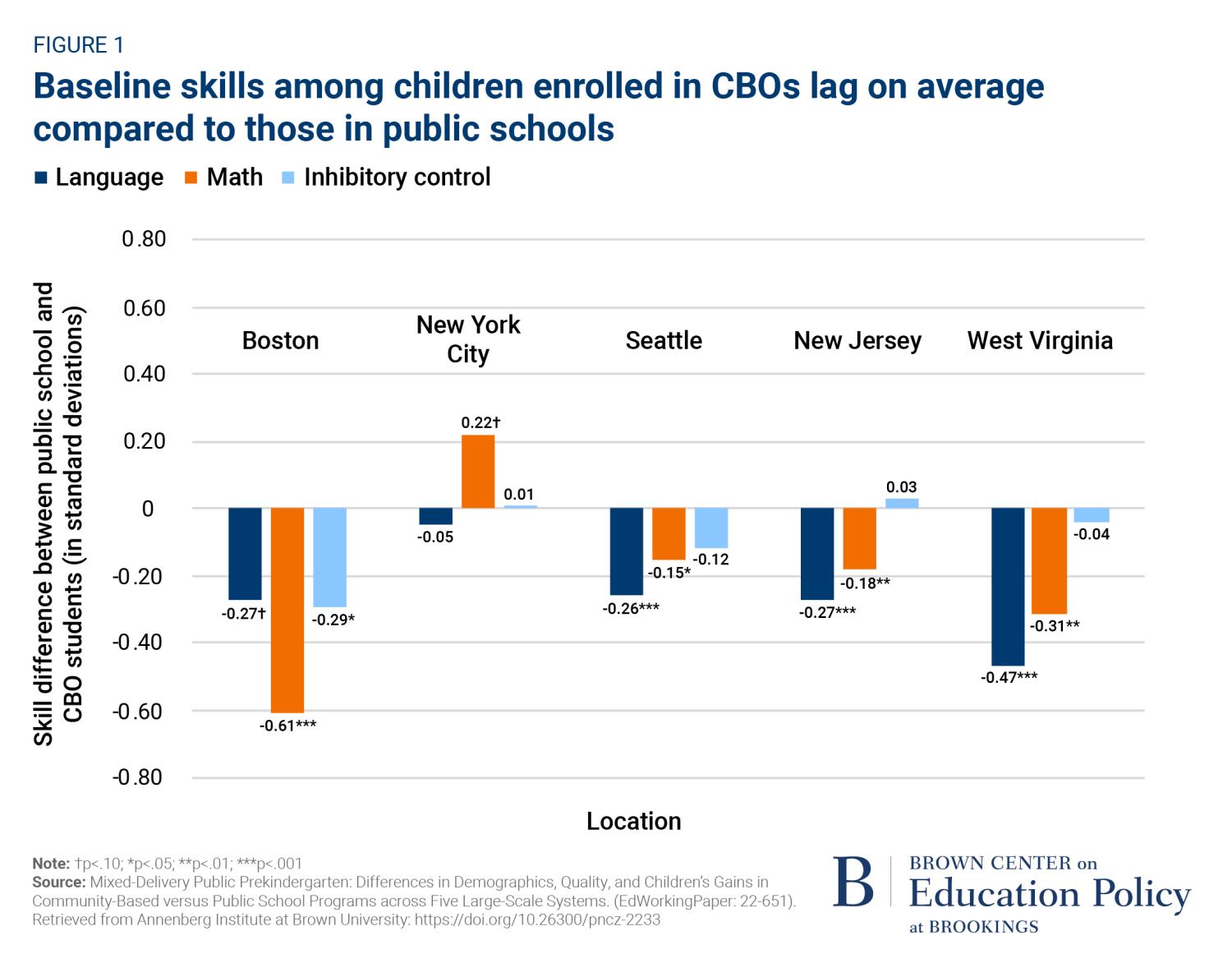

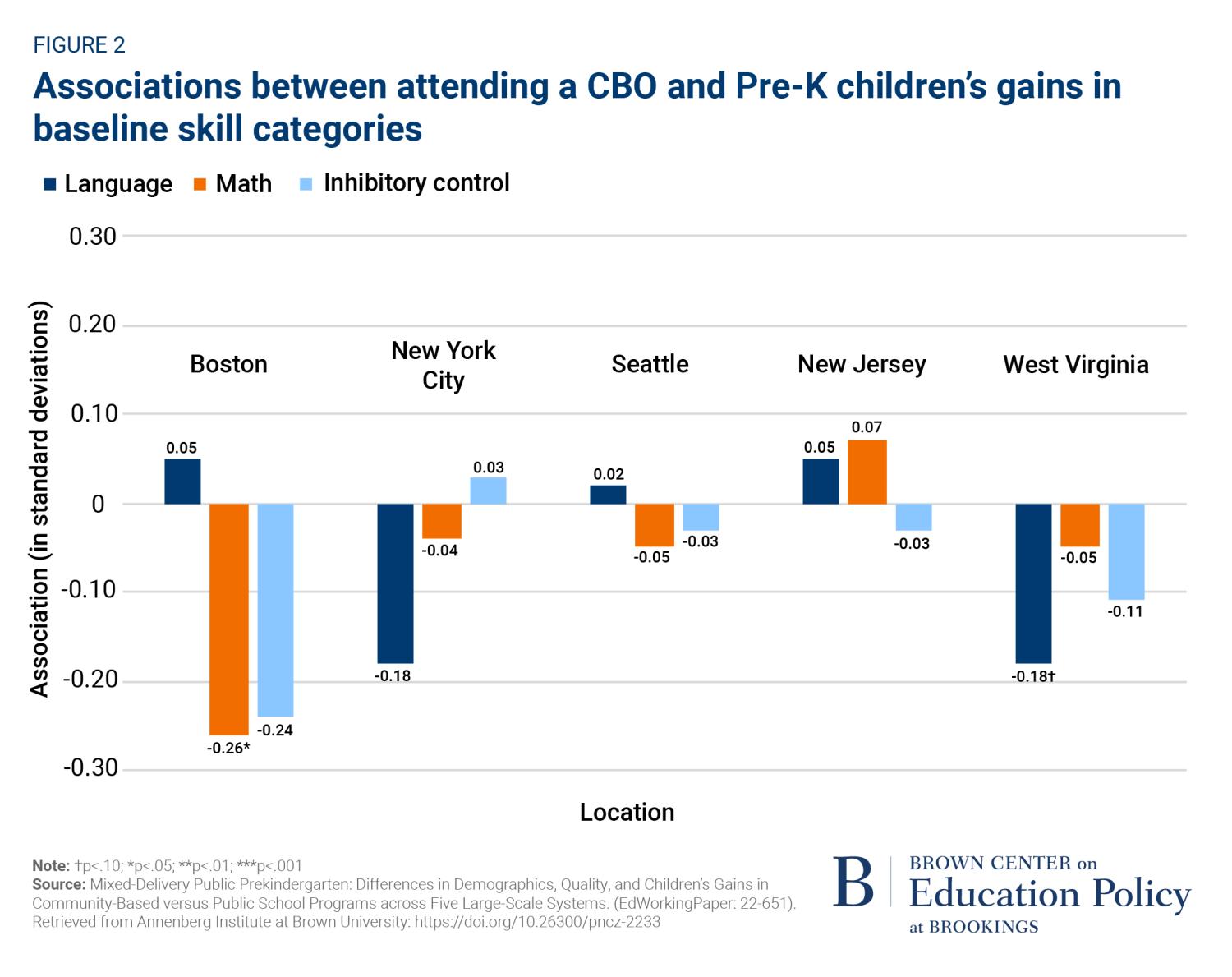

Children from marginalized backgrounds—including Black children, Latino children, and children from families with low incomes—were more likely to attend CBOs than public schools. Although, on average, these children all showed learning gains across the pre-K year, children in CBOs gained less overall than their peers in public schools. This is a surprising finding because children with more room to grow typically show larger learning gains than their peers. But in our study, children in CBOs started behind their public school peers on average (Figure 1) and gained less than children in public school on most comparisons (Figure 2). The largest differences represented nearly three months of learning.

To be sure, more research on this topic is needed, including studies on additional localities and with stronger designs. For example, studies that randomly assign children to CBO and public school-based programs are needed to identify the causal effects of setting. Although our study is descriptive, our findings do shine new light on a persistent problem. Even within systems that should be commended for taking explicit steps to improve equity—systems that in many ways have been leaders nationally in expanding access and improving quality—important differences in quality and children’s learning have persisted across settings.

Where to go from here

Solutions to these longstanding inequities aren’t easy, especially given the disproportionately devastating effects of the pandemic on CBO programs. So, what can localities do? At a minimum, our findings illustrate how and why localities should monitor equity by setting in their mixed-delivery systems. To our knowledge, this isn’t a common lens used by localities, but it should be. Currently, only about 60% of state-funded pre-K programs report enrollment by race/ethnicity and family income. The first step towards addressing these inequities is measuring them—a step that will require investments to build stronger early learning data systems.

Second, we did find some suggestive evidence that holding CBOs and public-school programs to the same standards might help. Specifically, the two localities in our study with smaller differences in teacher education, quality, and child gains by setting (Seattle and New Jersey) also had the fewest CBO-public school policy differences. But policies like pay and working conditions parity require resources that are scarce in many localities.

Federal COVID-19 relief funds can and should be used to implement more equitable policies in mixed-delivery systems. These are time limited, however, and the likelihood for new federal resources has been murky since the push for building a comprehensive 0-5 system stalled out last year. The looming funding cliff for ECE programs once COVID-19 relief funds expire could spur renewed momentum. If so, pre-pandemic data like our findings highlighting setting inequities—and complementary experimental work finding particularly large impacts of evidence-based investments in CBOs—demonstrate the importance of considering program setting when determining where resources should go.

It’s also important to highlight what could be counterproductive as a solution as well—concentrating programs in public schools instead or attempting to change who goes where. Without a significant increase in 0-5 early care and education funding at the federal level, a mixed-delivery approach is needed to stabilize 0-3 care and to give parents more choices. Further, we need data on how and why families make decisions within mixed-delivery systems. Many families may be picking CBOs because they offer hours that better match work schedules, to match their own linguistic and racial/ethnic background, or because a younger sibling can be served at the same location. We don’t know. We do know that some families do not apply to public pre-K at all when it is available, particularly families from historically marginalized groups. Any changes affecting where programs are located and who goes where require new data on family needs and voices. Otherwise, we risk reducing access and increasing inequities, particularly for children who stand to benefit the most.

The bottom line is that no locality has yet completely cracked this difficult nut—before the pandemic or since. Policymakers, advocates, and researchers should be asking hard questions about these longstanding issues, continuously assessing how program delivery is going across settings, and working toward new solutions to ensure access to high quality pre-K for all families.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

![Leo, left, and Jeffery, right, listen as their teacher, Justin Armbruster, goes through a math lesson at Rochester Elementary School in Rochester, Ill., Wednesday, September 15, 2021. Illinois students and school staff in K-12 and early childhood care centers are required to wear masks indoors because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Illinois students and school staff in K-12 and early childhood care centers are required to wear masks indoors because of the COVID-19 pandemic. [Justin L. Fowler/The State Journal-Register]Rochester School District](https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/2021-09-17T102557Z_1037560367_MT1USATODAY16767858_RTRMADP_3_LEO-LEFT-AND-JEFFERY-RIGHT-LISTEN-AS-THEIR-TEACHER.jpg?quality=75&w=500)