Preschool attendance in the United States grew only slightly over the most recent decade–with enrollment among 3- and 4-year-olds never reaching 50%–and survey evidence suggests the ongoing pandemic has pushed the numbers even lower. But there are signs that the momentum is shifting.

The latest federal COVID-19 relief package included a $1 billion infusion for Head Start, and the Biden administration’s latest budget proposal called for a similar increase for 2022. In addition, the president’s Build Back Better proposal includes universal preschool as one of its central planks. That legislation is likely doomed, but these proposals have reignited questions over whether publicly funded preschool is worth the investment from taxpayers.

Debate over preschool’s effectiveness has sparked controversy for decades. One common source of skepticism is an influential finding that, while preschool programs tend to improve children’s test scores in the short term, those gains tend to “fade out” by the time they reach elementary school. The latest example of this is a study of Tennessee’s pre-K program that reports results through sixth grade, and it has received considerable media attention in recent weeks. While we must acknowledge that other recent work questions the methodological soundness of “fade-out” findings, a more fundamental issue is that studies of test scores and elementary-school outcomes provide, at best, an incomplete answer to the question we really want to answer: Does preschool help children build skills that will benefit them throughout life, even into adulthood?

Our research, just published in American Economic Review, provides new evidence on this debate from the early years of Head Start. This period represented an enormous expansion of access to public preschool. As part of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s “War on Poverty,” Head Start was also explicitly intended to break the cycle of poverty. But, like today, its critics expressed skepticism about its effectiveness.

Our analysis uses a new, large-scale dataset that connects children’s exposure to Head Start in its early years to their outcomes as adults. These data allow us to test the effectiveness of preschool in terms of its effects on children’s lives–not just in terms of short-run test scores. Are Head Start children more likely to finish high school, go to college, have stable employment, or escape poverty?

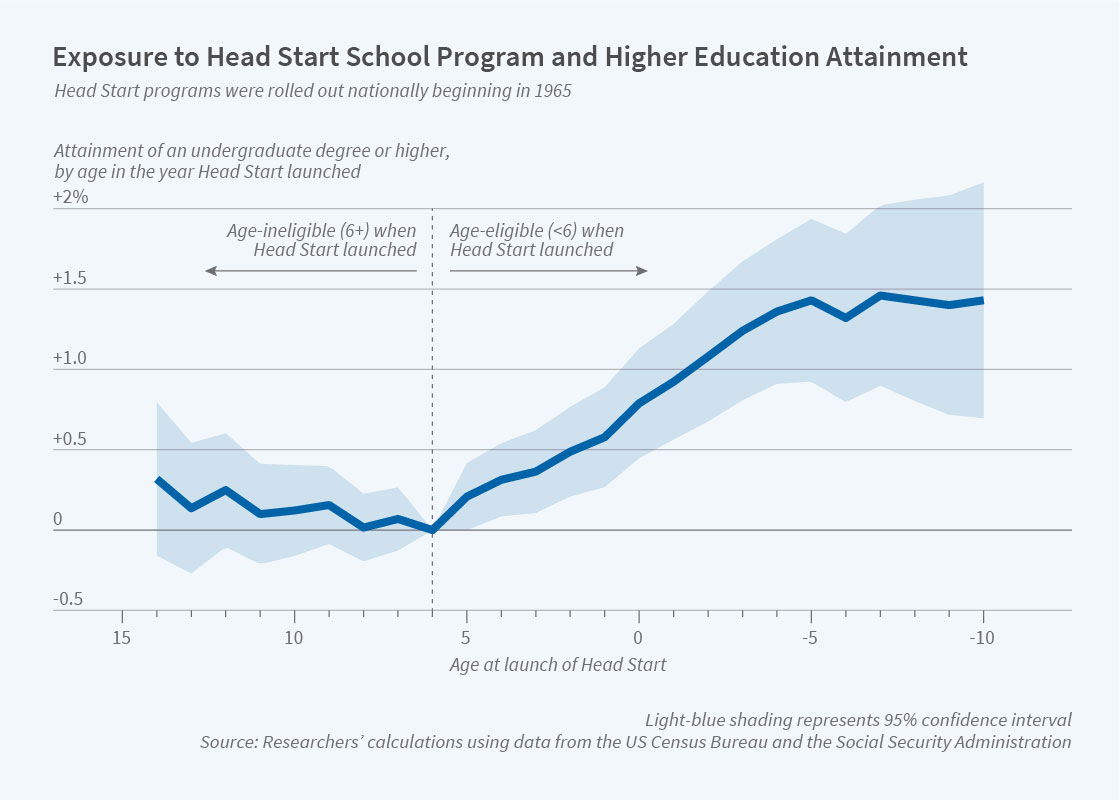

Our results show that Head Start had striking impacts on the long-run educational and economic success of its students. An example is shown in Figure 1 below. Compared to children who were age 6 (and less likely to benefit) when Head Start arrived, children ages 3 to 5 saw a substantial increase in the likelihood of earning a four-year college degree. The effect is largest for younger cohorts, who were eligible to attend Head Start for more years and benefited from the gradual improvement in classroom quality.

Our results show the gains were pervasive, appearing throughout the distribution of educational attainment: We estimate that students who were eligible for three years of a fully implemented program were 3% more likely to finish high school, 8.5% more likely to attend college, and 39% more likely to finish college.

These benefits translated to economic outcomes as well. Head Start attendees were more likely to work and have professional jobs. Female students were 32% less likely to live in poverty as adults, and male students saw a 42% decrease in the likelihood of receiving public assistance–an effect primarily driven by a reduction in the share relying on Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) to make ends meet.

The credibility of these findings rests on a simple research design rooted in the chaos of the early years of the War on Poverty. When Head Start launched in the 1960s and 1970s, it was established at different times in different places–in some places, not at all. As a result, access to Head Start was partly a matter of luck: Children who were 5 or younger when the program was launched enjoyed access to preschool, while their slightly older siblings and neighbors missed out because they were already in elementary school. Since these older children were similar to Head Start students in every other way, we are able to circumvent standard concerns about differences between parents who send their children to Head Start and those who don’t, thus allowing us to isolate Head Start’s impact on outcomes.

These results suggest that the children who attend preschool enjoy substantial benefits over the course of their lifetime. A skeptic might still be justified to ask: Is it worth the cost to taxpayers? A conservative, back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that the answer is yes.

Adjusted for inflation, the cost of Head Start in its early years was about $5,400 per student. From the taxpayer’s point of view, the benefits of the program came when these children reached adulthood: They were about 5% more likely to be employed, worked about 8.7% more hours per week, and were 27% less likely to receive public assistance from sources such as SSDI. If we account only for the extra income-tax revenue and the savings on SSDI benefits, the government’s initial investment in Head Start earned a healthy return of between 5% and 9%. From the students’ point of view, the rate of return to Head Start attendance (counting only the economic success the individual receives) is over 13%.

It is worth emphasizing that our calculations almost certainly underestimate the true effect of Head Start because they leave out savings on harder-to-measure expenditures, like the Medicare coverage granted to SSDI recipients as well as any immediate benefits associated with giving families access to childcare via Head Start. In addition, our calculations omit intergenerational effects of Head Start, which recent research suggests could be substantial.

What do these findings mean for the debate over whether to expand preschool today? We believe there are many reasons to be optimistic. One is that the Head Start program was launched at breakneck speed, and many of participants in the early period attended a program that was underfunded and lower quality than programs today. These early programs did not have the benefit of 40 years of research about best practices in preschool education. Yet even the nascent, underfunded Head Start programs of the 1960s delivered sizable benefits.

A second reason is that studies for more recent periods suggest large benefits from today’s programs as well. While findings such as the Tennessee pre-K evaluation remind us that gains may not always be positive or pervasive, its limitation is that it only looks at short-run effects. Another study of a recent cohort of Boston preschool students found no improvement in test scores during their younger years, but large, positive effects on high school graduation and college attendance–suggesting that the benefits of preschool may not appear in earlier years.

There is no guarantee that the children of today will benefit as much as Head Start kids from their parents’ and grandparents’ generation. But evidence is mounting that the benefits of universal pre-K are likely to show up in the long run, and that the lasting benefits of preschool programs need not be limited to the 1960s.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

![Leo, left, and Jeffery, right, listen as their teacher, Justin Armbruster, goes through a math lesson at Rochester Elementary School in Rochester, Ill., Wednesday, September 15, 2021. Illinois students and school staff in K-12 and early childhood care centers are required to wear masks indoors because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Illinois students and school staff in K-12 and early childhood care centers are required to wear masks indoors because of the COVID-19 pandemic. [Justin L. Fowler/The State Journal-Register]Rochester School District](https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/2021-09-17T102557Z_1037560367_MT1USATODAY16767858_RTRMADP_3_LEO-LEFT-AND-JEFFERY-RIGHT-LISTEN-AS-THEIR-TEACHER.jpg?quality=75&w=1500)