Over the last 18 months of the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers have compiled a host of metrics to describe its ongoing impact on children, who are suffering through school closures that may have immense effects on their life outcomes. Existing metrics describe students’ stymied academic progress, increasing depression, stress, and anxiety, decreasing college enrollment, and potential long-term economic setbacks. On most measures, students from economically disadvantaged and minoritized backgrounds have endured more remote learning and are suffering more than their more privileged peers.

Parents also have key insight into the extent to which and in which areas their kids may have been struggling. This insight can help guide educators and other community members supporting children and families to determine where to focus supports, and for whom. Therefore, we surveyed the same nationally representative sample of Understanding America Study (UAS) parents of K-12 children at three points in time: in October 2020 (when 28% had fully in-person school), April/May 2021 (when 50% had fully in-person school), and June 2021 (when 79% were on summer break).

We asked parents their level of concern about the amount of learning they felt their children were gaining during the school year, their social lives and psychological well-being, and their relationships with their peers and teachers. We collapsed the four possible responses into two categories: not concerned (which combined the “a little concerned” and “not at all concerned” responses) and concerned (“concerned” and “very concerned”).

We reached three main conclusions from our analysis.

Parents of in-person learners were less concerned than other parents

Compared to parents of children who attended school exclusively remotely, we found parents whose children attended only in-person during the 2020-21 academic year were meaningfully—and statistically significantly—less concerned about how much their child was learning, their engagement with school, and their social and emotional well-being (see Figure 1). The concern gap between parents of remote and in-person students was largest regarding the amount of learning (15 percentage points). These gaps are average differences without adjustment for demographic or other factors.

Figure 1: Parents of in-person learners were less concerned than parents of remote learners.

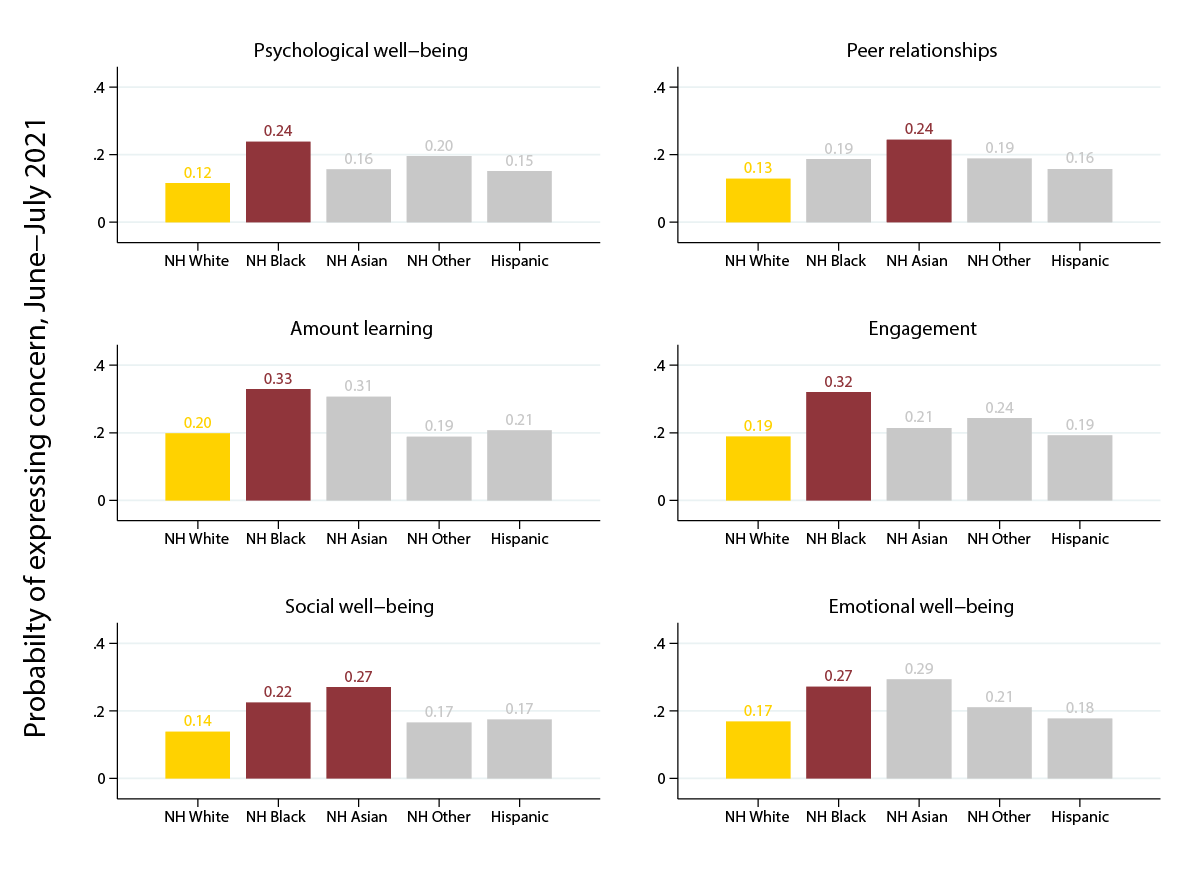

Black and Asian-American parents were more concerned than parents of other races

As shown in Figure 2 below, we also found large differences in parental concern across race/ethnic groups. Across most measures, Asian-American and Black parents expressed higher levels of concern relative to white parents. Asian-American parents were statistically significantly more likely than white parents to be concerned about their children’s social and emotional well-being.

Relating these first two findings, it is important to note that mode of attendance varied considerably by student race/ethnicity. For example, whereas 36% of white students attended exclusively in-person throughout the 2021-22 school year, 26% of Hispanic, 23% of Asian-American, and 21% of Black students did the same. Still, the results of supplementary analyses suggest that racial differences and modality differences largely persist when including both factors simultaneously in a regression.

Figure 2: Asian-American and Black parents expressed higher levels of concern than white parents.

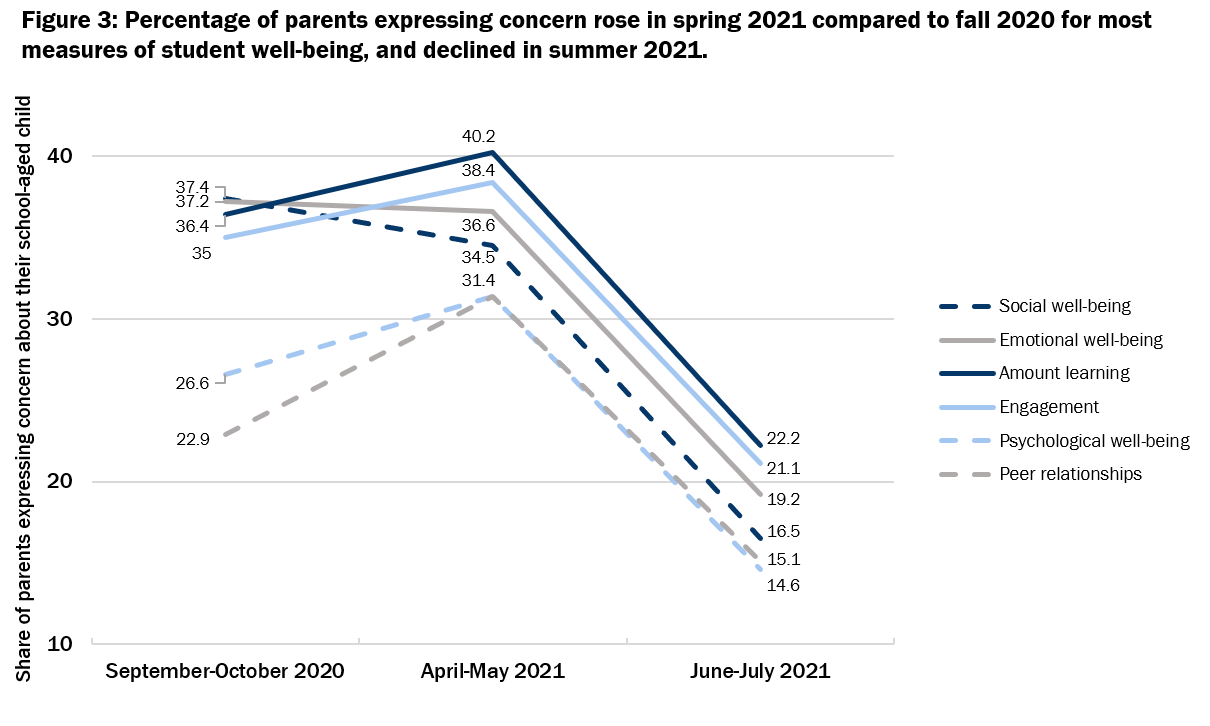

Concerns dropped precipitously at the beginning of summer 2021

When we broke out concerns over the three time points, we found parents’ concern about their children’s well-being was higher in spring 2021 than fall 2020, but it had dropped substantially by June 2021. In Figure 3 below, we show the percentage of parents who expressed concern about their children during each of the three time points. For nearly every measure of parental concern about their children, the percentage of parents expressing concern rose between fall 2020 and spring 2021, with two exceptions being students’ social well-being and their level of engagement in school. However, levels of concern fell sharply in summer 2021 for all students.

The declines in concern were especially pronounced for parents who responded to the survey after their child was out of school for the summer. For instance, while the percentage of parents concerned about the amount their child was learning rose nearly four percentage points between the fall and spring of the 2020/21 school year, it dropped approximately 18 percentage points between spring and summer 2021. This difference between the responses of parents whose children were still in school versus out of school for the summer remained even when accounting for parents’ race/ethnicity, family income, and other characteristics.

This analysis does not probe the reasons for the disparity between the responses of parents whose children were and were not still in school as of the timing of their survey responses. On the one hand, they could reflect real differences in parent attitudes, perhaps signaling that parents’ worst fears about the school year did not materialize. Alternatively, parents may have been less stressed in the summer when school was out. Parents’ responses may even indicate optimism about the upcoming school year, with most anticipating predominantly in-person instruction nationwide.

Interpreting parental concerns and looking forward

These results contribute to understanding the extent of COVID-19 on child well-being and among which groups. Parents of remote and hybrid learners were more concerned than parents of in-person learners. This result aligns with the widely accepted notion that most children’s well-being is better served attending school in-person, though the results we present here are descriptive and should not be interpreted causally.

Parents of Black and Asian-American children were more concerned than parents of white children. This result, in conjunction with the first, would suggest that parents of Black and Asian-American children would be keen to send their children to school in-person in fall 2021. However, as of August 2021, these groups—23% of Black and 20% of Asian-American—have disproportionate numbers of “school hesitant” parents relative to 15% of white parents. Both groups have been concerned about student safety, from COVID-19 and from racial discrimination. These results bolster those from the recent Education Next poll showing stark racial differences in preferences for COVID-19 safety protocols, indicating more needs to be done to ensure that Black and Asian-American families feel safe—and are safe—in schools.

Parents were far less concerned at the end of the 2020-21 school year relative to the fall and spring. These results may help to contextualize the Education Next results showing little change in the public’s annual evaluations of public schools’ quality from the end of the school year pre-pandemic as compared to May/June 2021. Lower concern levels at the end of the year may have driven tepid parent interest in tutoring and summer school in spring 2021. They also suggest that parents may be more interested in enrolling their children in extended time and other acceleration programs during the school year rather than during the summer.

Finally, our data reveal another interesting phenomenon. Between December 2020 and February 2021, we asked UAS respondents (the full panel as well as the parent subsample) how concerned they were that today’s generation of K-12 students may not make as much academic progress this year as they would during a typical academic year. Across groups, levels of concern ranged from 70% to over 80%—more than twice the range of concern we found when we asked parents about their own children. The difference between these two sets of results is worth investigating further. Why do Americans feel so differently about their own children’s progress and other children’s progress? Which results more accurately reflect the degree of damage done by school closures and the COVID-19 pandemic?

Overall, our results offer some room for optimism—despite all that has gone on, parents’ level of concern about their own children was not as high over the summer as it was during the 2020-21 school year. Still, there were important gaps corresponding to inequalities in access to in-person instruction. As the 2021 academic year continues and the Delta variant affects in-person learning opportunities, we will continue to monitor parents’ attitudes, experiences, and concerns toward their children’s education.

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the National Science Foundation Grants No.2037179 and 2120194, and the Hewlett Foundation. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding organizations. We are also grateful to Amie Rapaport, Daniel Silver, Michael Fienberg, and the UAS administration team for their contributions to this work.

Commentary

Concerns about child well-being during the 2020-21 school year were greatest among parents of remote learners

September 23, 2021