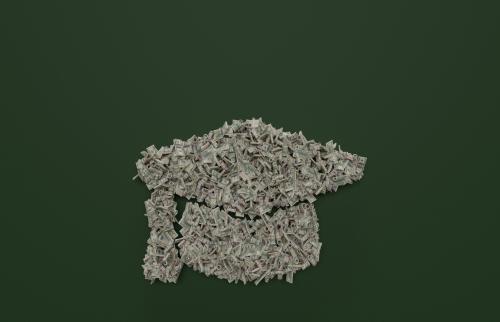

Tuition and fees at four-year colleges have more than doubled in the last 20 years, rising significantly faster than median wages. Although college attendance rates have increased over this time period, the gap between low-income and high-income families has not narrowed.

Financial aid programs are one way to help low-income students overcome the short-term challenges of paying for higher education. Beginning with early work on the Pell Grant and other aid programs, research has pointed to aid having positive impacts on college attendance, persistence, and, in a few studies, degree completion. Yet research to date has likely understated the total societal returns to financial aid programs, as some of the benefits cannot be observed until many years after students leave the college campus. State support of higher education often comes under scrutiny due to budget concerns. Yet, if these subsidies lead to better job prospects and higher earnings, and produce a positive return to the state in the form of tax revenues, the state could possibly be underinvesting in students’ higher education.

To investigate financial aid’s long-term impacts, we developed a relationship with the California Student Aid Commission, which administers the Cal Grant program, one of the largest state-based financial aid programs in the nation. State programs that allocate aid based on either financial need or academic merit have become more prominent over the past two decades, with funding increasing by 83% from 2002 to 2012. At the time of our study (full paper here), students were eligible for the Cal Grant if they submitted the FAFSA, were low- or middle-income (e.g., the income limit for a family of three was $59,000 in 2000, which would be about $87,000 in 2019), and had a high school GPA of roughly 3.0 or higher. The program was extremely generous, offering four years of full tuition at any in-state public college or close to $10,000 per year to attend an in-state private college. Low-income students were also given a cash subsidy of roughly $1,500 per year for any student, including those attending community colleges.

We identified tens of thousands of students who graduated from high school from 1998 through 2000 and examined their college enrollment, degree completion, and wage outcomes for 14 years after high school. This approach was feasible for two reasons. First, we were able to link the FAFSA applications of Cal Grant students to federal tax return data held by the U.S. Department of the Treasury. Having federal tax data enabled us to track students across the country, which would not have been possible with state-specific data. Second, eligibility for the Cal Grant was determined by a series of income and GPA cutoffs that were unknown to applicants. We produced causal estimates of Cal Grant impacts by comparing essentially identical students who fell just below and above these eligibility thresholds (using a regression discontinuity design).

Results

Overall, we found that financial aid led to positive long-term impacts on obtaining both bachelor’s and graduate degrees and, for some students, raised longer-run annual earnings and the likelihood that they resided in California. Students with the lowest income and GPA were 10% (4.6 percentage points) more likely to earn a bachelor’s degree. This is not due to increases in college enrollment, but rather that aid reduced the likelihood that students dropped out along the way. Students did not stop there, as they were 27% (3.1 percentage points) more likely to continue their schooling and earn a graduate degree. As a result of these changes, earnings reported on 1098 tax forms were about 3 to 4% higher between the ages of 28 to 32.

We observed more muted effects among higher-income and higher-GPA students. Many of these students used state money to shift into more expensive—but not necessarily higher quality—private colleges. Bachelor’s and graduate degree completion increased but by smaller amounts, and we were unable to detect changes in earnings. (Our project lacks statistical power to detect small gains or losses in earnings.) Yet states might still be interested in subsidizing these students, as they were about 1% (2.4 percentage points) more likely to reside in California, thus making significant contributions to the state’s tax base.

One important finding in our study is that financial aid may have only small impacts on student debt. We find that the size of student’s federal loans is unchanged after 10 years, likely as the Cal Grant raised student expenditures by increasing undergraduate persistence, increasing graduate school enrollment, and inducing some students to attend more expensive institutions. One shortcoming is that we do not observe all debt, just federal loans; more research is needed in this area.

Conclusion

State sponsored merit- and need-based aid constitutes one of the most important and fastest growing sources of student assistance for postsecondary education. Using California’s large and generous state-aid program, we find that aid eligibility led to long-term increases in degree completion and wages, particularly for the neediest students. We estimate that the program could increase individual earnings of eligible low-income, low-GPA students by a net present value of $40,000 to $50,000 over their lifetime, yet in our data the state paid just over $4,000 per eligible student (only a share of eligible students participate and persist for all four years; estimates of costs and benefits to participating students are higher). Although only a fraction of these increased wages would be returned to the state through taxes, the results suggest that the benefits of aid programs may be frequently understated without taking these long-term impacts into account. Similar work on the long-term impacts of state aid in West Virginia and federal aid in Texas generally supports our findings.

“State sponsored merit- and need-based aid constitutes one of the most important and fastest growing sources of student assistance for postsecondary education.”

We believe our results are likely to hold broadly, even though we only study California-based students in the late 1990s. At the time, California had a highly subsidized postsecondary system with high attendance rates, suggesting that students in states with more expensive and less heavily attended institutions may see equal or larger impacts on degree completion. Equally important is that we focus only on a subset of relatively highly motivated students who have taken the time to file a FAFSA form and a Cal Grant application; getting financial aid to students who do not typically take these steps may lead to stronger attendance and completion outcomes.

How can we ensure that financial aid programs best support student success? The current version of the Cal Grant program uses transparent eligibility criteria, subsidizes enrollment in every postsecondary sector, and is a “first-dollar” scholarship, meaning that state aid is applied before other financial aid programs. Transparency matters, because offering students a clear and early message that college is affordable typically increases access, as in the case of “Promise” programs or targeted outreach programs such as Michigan’s HAIL scholarship. Programs that restrict aid to a subset of postsecondary institutions, such as Massachusetts’s Adams Scholarship, may lead students to enroll in less selective colleges, ultimately decreasing graduation rates. Programs that take a “last-dollar” approach, where existing forms of aid such as the Pell Grant are applied prior to the newly allocated funds, are often criticized as regressive for directing more money to middle-income students than those most in need.

Our results suggest that a financial aid program like Cal Grant can indeed produce long-term impacts on both educational and labor force outcomes, with particular benefits for low-income students with low GPAs. States should consider these potential benefits when designing or weighing the explicit costs of these programs.

Commentary

Evidence from California on the long-run benefits of financial aid

April 4, 2019