Editor’s Note: This blog post draws from the longer paper published today by the Brown Center on Education Policy entitled “Educational success in two Inner London boroughs: Lessons for the U.S.”

As education policymakers in the United States grapple with the issue of how to improve low performing schools in urban areas with large concentrations of low-income pupils, they might want to consider the experience of their counterparts in London.

The academic performance of primary and secondary school pupils in London has improved dramatically since the late 1990s and now exceeds national averages. Strikingly, the improvement is largely attributable to the rapid achievement gains of low income students in the 13 boroughs of Inner London that include the greatest concentrations of low-income and ethnic minority students. This remarkably strong performance of London students was first highlighted in an article in the Financial Times and has been dubbed the “London Effect.”

During the fall, we spent a month in London examining the factors that contributed to the success of primary (elementary) school pupils in two of these Inner London boroughs, Hackney and Tower Hamlets. Both boroughs are economically disadvantaged, have large concentrations of immigrants and ethnic minority pupils, and were ranked among the country’s three lowest achieving boroughs in 1996. Both have made tremendous strides in student achievement. Pupils in Tower Hamlets make large improvements in the early 2000s and reaching national averages in 2004, while those in Hackney made more gradual progress, starting in 2006 and reaching the national averages in 2011.

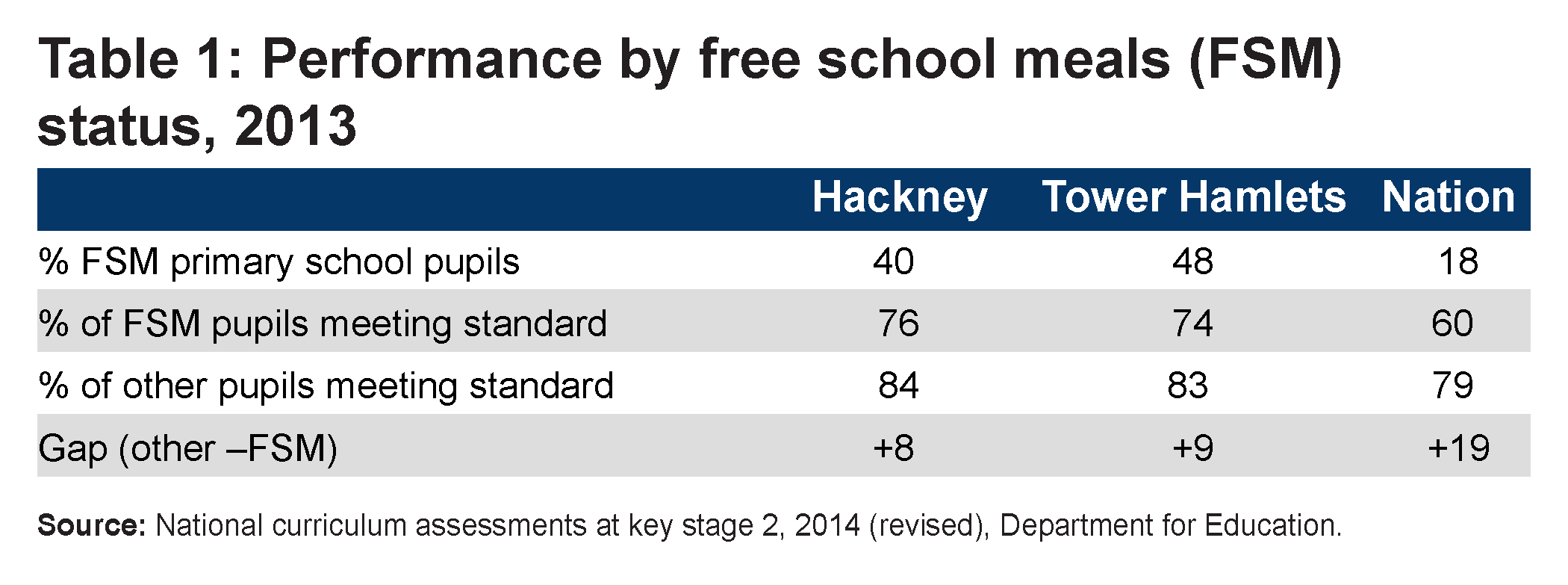

Table 1 shows the percentage of pupils meeting academic standards in Hackney and Tower Hamlets in 2013 by free school meal status (a measure of student disadvantage). Students who met standards scored at level 4 or above in reading, writing and math – the equivalent of being at grade level. The table shows that while free school meal (FSM) students in our two London boroughs continue to underperform relative to their more advantaged local counterparts, their achievement levels far exceed that of FSM students in the nation. Moreover, the gap between the achievement of FSM and non-FSM students in Hackney and Tower Hamlets is less than half that in the nation.

What did Hackney and Tower Hamlets do right?

Observers have noted several contextual factors that may have contributed to the educational successes in the two boroughs. These include the changing ethnic mix of the students, gentrification and economic growth, increases in national school funding targeted at boroughs with higher proportions of disadvantaged students, and other national or London-specific policy initiatives. We conclude, however, that these factors are not the whole story. In particular they do not account for the difference in the timing of the success in the two boroughs or for the fact that in both boroughs the schools themselves got better.

We were able to determine that the schools improved by tracking the judgments made by Ofsted, England’s school inspectorate. Ofsted sends review teams to each state-funded school on a periodic basic to review the leadership and managerial capacity of the school, its internal policies and practices, and student outcomes relative to those of comparable students. Based on our review of Ofsted’s public reports on each school over time, we found that the schools in Tower Hamlets had improved dramatically by the early 2000s, and those in Hackney somewhat later.

Through research, observation, and interviews with English educators, we found that a key factor in the success in both boroughs was strong leadership at the borough level. In Tower Hamlets that leadership emerged in the late 1990s in the form of a new director of education services who gained the strong support of the Borough Council. In Hackney, the leadership took the form of a non-profit organization which, because of a dysfunctional city council, was given responsibility for education in the borough starting in 2002 for a 10-year period. After addressing crucial problems at the secondary level, the new leaders in Hackney were able to turn their attention to the primary schools by the middle of the decade.

In both boroughs leaders were driven by essentially the same vision of how to operate a successful urban district. This vision rested on the twin pillars of (1) a commitment to high academic expectations for all children, including those from low-income backgrounds, and (2) the importance of establishing a culture of mutual responsibility and of cooperation throughout the borough. The borough leaders worked hard to make sure this vision was shared by all head teachers (school principals) throughout the borough who could work with other head teachers and their own teachers to implement it. They typically described their educational work as the pursuit of a “moral purpose.”

Importantly, the leaders understood that fulfilling their two-pronged shared vision requires a systemic approach in which all elements involved in the delivery of education work together toward common goals. The education system is seen not as a collection of independent schools competing with each other but rather as a coherent whole. Operationally, such an approach implies borough-wide coordination of curriculum, professional development, assessment and other key elements as well as cooperative deployment of teachers and other personnel. Under such a systemic approach, success is defined not by the performance of a few high-flying schools but by how well all schools are doing, especially those serving the most disadvantaged students.

Importantly, schools in both boroughs pursued a range of strategies to address the needs of disadvantaged students. These included the use of detailed and sophisticated data to monitor individual pupil performance and to diagnose their learning needs; early interventions to address the learning deficiencies that they identified; the development of strong relationships with families; and efforts to address the social, emotional, and other needs of families in order to reduce the stress on their children.

What can U.S. policymakers learn?

One of the first things to note is that both boroughs were well-funded. Having resources, of course, is no guarantee that they will be well spent, but strong financial support from the central government enabled borough and school leaders to implement promising policies and programs. Aside from the value of adequate funding, we came away with three major lessons for U.S. policymakers.

Lesson 1. The power of district-wide reforms

Much school turnaround activity in the U.S. is centered on reforming isolated low-performing schools rather than the district-wide systems of which they are a part. In contrast, the London strategy was area wide. The lesson that we take from this experience is that states would do well to think in terms of area-wide strategies, rather than reform strategies that focus on individual schools or that combine schools into “achievement zones” that cut across district lines. States would be well advised to recognize that individual schools are embedded in districts and that well- funded districts with strong leaders have an important role to play in assuring high quality schooling for all children.

Lesson 2. The benefits of broader accountability systems

Under No Child Left Behind, the U.S. federal government held individual schools accountable for student outcomes primarily as measured by test scores in math and reading. Under the new Every Child Succeeds Act, states now have more flexibility to explore other forms of accountability. One way to do this, taking a cue from England’s inspection system, is to move beyond the use of student test scores by incorporating input from trained professional inspectors. Such inspectors would visit schools and then report on the quality of their internal policies and practices that contribute not only to student achievement but also to the quality of the child’s experience in school. In addition, the London experience suggests that states should consider expanding their accountability programs to cover the performance of whole school districts as well as that of individual schools.

Lesson 3. The need for support within school systems for disadvantaged students

The major U.S. federal education initiatives of the last 15 years – No Child Left Behind, Race to the Top, and School Improvement Grants – have made strong declarations about the importance of high expectations for all children. However, insufficient attention has been given to the supports needed to meet those expectations. The London experience illustrates how ample resources can be effectively mobilized to address the challenges that many low-income children bring to school so that they can achieve to their potential. We have seen some progress recently in the U.S. in the greater emphasis on early childhood programs, the expansion of health care coverage, and the provision of nutrition supports and wraparound social services in some communities. Nonetheless large numbers of disadvantaged children lack the individualized attention they need to succeed, and many schools are not equipped to help address the emotional and other problems that such children bring to the classroom. The London experience indicates the value of funding programs that direct more money to districts with high proportions of needy students and the role that districts can play in assuring that individual schools have the resources and capacity they need to meet the needs of the specific children they serve.

Although districts and schools obviously lack the capability to eliminate poverty in general, they do have the ability to mitigate many of the ways in which poverty has a negative impact on student learning. Some of the English educators with whom we spoke suggested that there was nothing particularly new or innovative about the strategies they were pursuing. They were simply implementing fundamental time-honored principles of effective education by establishing an overall vision and working closely with strong head teachers and other leaders to implement it.

Final thought

London is one of the relatively few urban areas in any developed country to have found a way to generate educational excellence while serving large concentrations of low-income pupils. The London Effect is real. To American eyes, the educational successes in Tower Hamlets and Hackney are particularly noteworthy because of the overall approach that they took. Rather than trying to improve schools through governance, structural, or other changes that have little direct impact on what happens in classrooms, they focused their attention on time-honored fundamentals of education. And it worked!

Liana Stiegler contributed to this post.

Commentary

The “London Effect”: What U.S. policymakers can learn from the success of Inner London schools

February 17, 2016