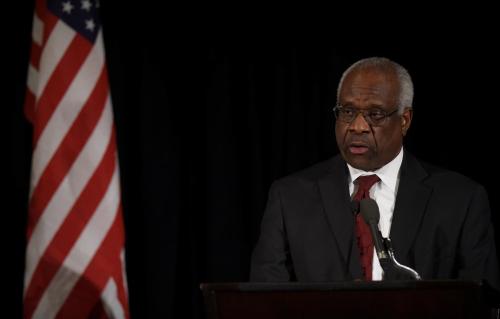

Another shoe dropped at the Supreme Court last month. Once more, a ProPublica article alleges ethical impropriety by a Supreme Court justice. The article asserts that in 2018 Justice Clarence Thomas was flown on a private jet to speak at a fundraising summit for donors to the Koch network, which he failed to report on his financial disclosure forms. According to the article, at the summit the Koch donors also strategized about Supreme Court matters.

A former federal district judge commented in the article that it took his breath away to learn that Justice Thomas had attended this fundraising event, and that if that judge had gone to a Koch summit, “I’d have gotten a letter that would’ve commenced a disciplinary proceeding.” The former judge added, “What you are seeing is a slow creep toward unethical behavior. Do it if you can get away with it.”

Are these new allegations true? We don’t know. Do they undermine trust in the Court? Yes. Will the Supreme Court take any action to get to the bottom of them? Unlikely, if history is any guide.

The Supreme Court has not taken the basic step of adopting an ethics code for its Justices. And the Supreme Court lacks a credible internal investigative mechanism to investigate serious allegations of ethical violations. Without an investigation into the recent allegations, the truth or falsity of them will be viewed through a partisan lens, and the facts of what occurred will remain in dispute. As a result, faith in the ethics, impartiality, and independence of the Court will continue to plummet.

It is long past time to rectify these deficiencies. The Supreme Court needs an ethics code and an effective mechanism to investigate facts related to serious allegations of judicial misconduct.

How the executive branch handles allegations of ethical misconduct is instructive. It has applicable ethical codes as well as mechanisms to investigate allegations of misconduct, including ethical violations. To illustrate how allegations similar to those lodged by ProPublica would be handled in the executive branch, consider this hypothetical scenario. Imagine that the media reported credible allegations that a high-level Department of Energy official was flown on a private jet to a dinner for donors intent on influencing Energy Department regulations related to fossil fuels. Allegedly, the plane was arranged by an advocate for regulations to curtail climate change, and the energy official failed to report the trip on his financial disclosure forms.

Undoubtedly, this allegation would be reviewed by one or more oversight entities. The Office of Special Counsel would assess whether the official violated the Hatch Act, which prohibits executive branch officials from participating in activities to promote a partisan political group. The Office of Government Ethics would examine the official’s financial disclosure forms and possibly refer the matter for investigation to an inspector general or the Justice Department.

Most important, the inspector general (IG) of the Energy Department would also review the allegations, to determine if the evidence seemed credible and the allegations of misconduct serious. If so, the IG would likely conduct a full investigation into the facts of the case. The IG would interview the energy official and sponsors of the event, other attendees, and other individuals with knowledge about the trip. The IG would review documentary evidence, including emails, about the planning for the trip. The IG could also subpoena relevant documents from non-governmental organizations or individuals. The IG would examine whether the official had exhibited a pattern of improperly accepting gifts and previously omitting such gifts on financial disclosure forms to assess whether the alleged misconduct was intentional or inadvertent.

If the energy official said that he had consulted with agency counsel about the ethics of flying on a private plane to attend such an event, the IG would interview the counsel to determine what exactly the official had told counsel about the trip and what the counsel had advised. Often, IGs find that officials seeking ethics advice only provide selected details to counsel, rather than the full story. In those cases, a claim that a trip was approved by agency counsel is not persuasive.

At the end of the IG investigation, the IG would refer the investigative report to agency leaders for appropriate action, if the allegations were substantiated, and also ordinarily issue a public report detailing the full facts of what the IG uncovered. As a result, while the energy official, agency leaders, Congress, and the public might disagree on the appropriate response to the substantiated allegations, at least they would have a similar understanding about the facts of the incident. And if the IG report cleared the official, the report would more credibly put the allegations to rest.

Unfortunately, similar investigations are not conducted when serious allegations arise about ethical misconduct by Supreme Court justices, as they have recently with increasing frequency. The Supreme Court does not have – but needs — an experienced, permanent internal investigative capacity.

For example, when the draft of the Dobbs opinion was leaked, the Chief Justice called the leak an egregious breach of trust and assigned the matter to the Court’s Marshal to investigate. She did not have the experience or independence to conduct such an investigation, and her investigation was limited and flawed.

Another ProPublica article accused Justice Alito of having accepted undisclosed luxury travel and vacations from a hedge fund billionaire who allegedly had interests before the Court, but no investigation seems to have been conducted. Justice Alito issued his own prebuttal in the Wall Street Journal before the ProPublica article was published, disputing its allegations. This caused intensified debate on the facts of what had occurred, as well as on the propriety of Justice Alito providing his prebuttal in a newspaper opinion piece.

Other ProPublica articles alleged that Justice Thomas failed to report many gifts from Harlan Crow on his financial disclosure forms, such as Crow’s paying school tuition for Thomas’s grandnephew and Crow’s purchase of his mother’s home at above-market value. Chief Justice Roberts sent complaints about Justice Thomas’s financial disclosures to the Judicial Conference Committee on Financial Disclosure, composed of lower court federal judges “responsible for addressing allegations of errors or omissions in the filings of financial disclosure reports.” We have heard nothing from this committee or whether there will be a public report describing any factual findings.

The Court’s response to these allegations is not optimal. Although Congress could play a role by legislating reforms, such as imposing an ethics code on the Court and establishing an investigative body to investigate judicial misconduct, such legislation is unlikely to be enacted. If passed, the legislation might not survive a separation of powers constitutional challenge, particularly since the Court itself would decide its constitutionality.

Rather, the Court should police itself, which it does not do now. First, the Supreme Court should adopt a code of ethics. A judicial code of conduct applies to lower federal court judges, but not to the Supreme Court. The Court should adopt its own code. This would affirm that every Justice should observe certain ethical norms, rather than determine themselves which ethical standards apply.

Second, the Supreme Court should seek to establish a professional, permanent investigative office, with powers like an inspector general, to investigate serious allegations of judicial misconduct as well as other allegations of fraud or abuse in the judiciary’s administrative operations. Unaddressed allegations of ethical violations tarnish the entire Court, as well as confidence in the impartiality of its decisions.

The investigative entity could be called something other than an inspector general, such as an ethics investigation counsel, or an office of compliance, as long as the office had the experience, independence, and resources to credibly investigate serious allegations of misconduct. Preferably, the Court would seek, or agree to, a statutory basis for the office, with a reasonable appropriation to staff the office.

The Court may be concerned, however, that such an office, whatever its title, would likely be inundated with petty, partisan complaints. That concern could be addressed by tasking the office with investigating only the most serious allegations that have some indicia of credibility. Most of the complaints would not require a response from the Justices or need to be investigated.

This investigative office would not need all the powers and responsibilities of traditional inspectors general in the executive branch, such as requirements to report to Congress, criminal law enforcement authority, or some of the other duties that IGs exercise. And the office should have no responsibility for investigating any matter involving judicial decisions, including recusal decisions. To address separation of powers concerns, the IG could be appointed by the Chief Justice or the Court, like IGs in several federal agencies who are appointed by the head of the agency.

The Court should adopt an ethics code and seek to create an effective and credible internal oversight mechanism. Otherwise, trust and confidence in the ethics and impartiality of the Court, which is so essential to our democracy and the rule of law, will decline even further. This is not good for anyone, including the Court.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edYet another ethics allegation — When will the Supreme Court act?

October 2, 2023