President Biden’s July 29 proposal for undoing the Supreme Court’s presidential immunity decision and imposing term limits on the justices also “call[ed] for a binding code of conduct for the Supreme Court.”

Biden’s symbolic and short-on-specifics recommendations and the predictable criticisms they kicked up have overshadowed an idea that Justice Elena Kagan offered days earlier to put some teeth in the Court’s November 2023 Code of Conduct.

Responding to a question at the U.S. Ninth Circuit’s judicial conference, she endorsed1 having other federal judges assess complaints alleging misconduct by Supreme Court justices. Kagan said that the “the rules [i.e., the Code] that we put out are good ones,” but while “rules usually have enforcement mechanisms attached to them, this set of rules does not”— “a fair” criticism.

A “good solution,” she said, would be “[i]f the chief justice appointed some sort of committee of highly respected judges with a great deal of experience with a reputation for fairness.” She emphasized that she was speaking only for herself and not hinting about a plan in the works. But she surely knew the question could arise, so it was hardly a spur-of-the-moment response.

The Wall Street Journal editorial page dismissed the proposal as unworkable and “constitutionally dubious.” Other commentators made questionable assumptions about how it would work or said it was little more than a public relations ploy. But, given the polarized Congress’s inability to enact a mandatory judicial ethics regime for the Court and the infeasibility of the Court’s creating one by itself, Kagan’s idea may—emphasis on “may”—be the half-loaf that is better than none.

What are the pros and cons of a non-statutory committee of lower court judges appointed by the chief justice to consider complaints of Supreme Court justice misconduct and how might such a committee operate? The short answer that I see: It wouldn’t function as a judicial conduct commission for the Court but could be a neutral forum to provide determinations of whether a justice committed misconduct—determinations akin to public reprimands, one of the enforcement tools that conduct commissions regularly employ.

Biden contrasted the Court’s Code—“weak and self-enforced”— to what he and countless others have mislabeled the “enforceable code…that applies to every other federal judge.” He thus perpetuated the confusion between the federal judiciary’s advisory code of judicial conduct and the1980 Judicial Conduct Act, the statutory created mechanism to evaluate and take appropriate action on judicial conduct complaints about lower federal court judges.

Biden’s statement, however imprecise, still highlights the fact that Supreme Court justices are the only federal judges for which there is no formal mechanism to receive and assess complaints of misconduct. Unease with the Court’s exempt status is not new. In 1976 hearings on a forerunner of the 1980 Act, Senate Judiciary subcommittee chair Quentin Burdick (D-N.D.) put it simply: “I don’t know how to answer somebody in my hometown, saying ‘Why do you treat the district judge here in Fargo differently than you treat the Supreme Court judge…?”

One can acknowledge the uneven treatment but worry that a cure might be worse. Kagan herself, while acknowledging the need for enforcement, said who should do so is “a super hard question.” The “enforcers should be judges” (not a universal view but a practical one), but it would be “quite bad…for [the justices] to do it to each other.” That leaves lower court judges, which “creates perplexities” (“we review all of your decisions and then you’re…reviewing our decisions and that’s not usually the case”).

Those “perplexities” underlay stated opposition to legislation in the current Congress that would have five chief circuit judges, randomly selected by the Court, evaluate complaints against justices and report findings to the other justices, who could, depending on the findings, impose “disciplinary actions.” Objectors criticized having lower court judges “preside over their bosses.” But judges’ assessing the conduct of judges who review their judicial decisions on appeal is not necessarily what a Washington Post critic called “distorting the judicial hierarchy.” For almost 50 years, district judges have been members of the committees, councils, and conferences that review allegations of misconduct by “their bosses,” circuit judges. (And the Court’s Code explains that, “for purposes of sound judicial administration,” justices file their statutorily mandated financial disclosure reports with the U.S. Judicial Conference, the statutory council of circuit chief judges and district judges that provides administrative governance and oversight of the lower courts.)

Some have tried to constitutionalize the “perplexity.” The Wall Street Journal editorial page noted that the Constitution established the Supreme Court but Congress created the other courts. “A lower-court tribunal would therefore subject the High Court to supervision by a creature of Congress, which is constitutionally dubious.” We can assess later whether Kagan proposed a “tribunal” and whether it would “supervise” the Court. But even if the proposed committee’s role were a form of supervision, what would make it “dubious”? Are Internal Revenue Service audits of the president’s tax returns “constitutionally dubious”?

Still, that Kagan’s proposal responds to a need, and is consistent with federal judicial conduct statutes, doesn’t mean it will work. Her idea raises questions of detail that necessarily went undiscussed in her four-minute conversation with Arizona Bankruptcy Judge Madeleine Wanslee.

Committee status and mission

Implied but unspoken in Kagan’s brief proposal is that the committee would receive and investigate allegations of misconduct by justices—allegations filed by others or, we can presume, raised on the committee’s own initiative, based on information available to it (equivalent to the Judicial Conduct Act’s authorizing chief judges to “identify” a complaint).

Kagan envisioned the committee as a creature of the Court itself, not a statutory body or part of the Judicial Conference. She talked of the chief justice’s appointing the committee, which he could do, but as a practical matter, it would need buy-in by all the justices. More on that later.

Resources

The committee would need administrative support that Congress would have to fund through appropriations. The Wall Street Journal is no doubt correct that the committee’s creation would “encourage frivolous complaints,” but retaining a staff to screen frivolous and otherwise clearly unmeritorious complaints is the price to pay for a transparent and accountable complaint mechanism.

One sticky question is not staff resources but authority, particularly what authority or resources the committee would have to compel witness testimony.

Reporting

For credibility, the committee would need to establish some kind of reporting mechanism, similar to but less elaborate than what Congress has required2for the 1980 Act’s operations. The committee would also need policies about when to publicize or formally acknowledge the fact that it is pursuing an investigation.

Workload

The committee would, as noted, attract frivolous complaints, but we should not overestimate the task the committee would face. Last year, under the 1980 Judicial Conduct Act, which applies to the entire lower federal judiciary of about 2,400, chief judges dismissed slightly over 1,300 complaints. Over four-fifths of the dismissals were because the complaints objected to judicial decisions (complaints not cognizable under the Act), a quarter were frivolous, and two-thirds presented insufficient evidence (dismissals could be for multiple reasons). Chief circuit judges found only nine complaints that presented facts reasonably in dispute and thus merited the creation of investigating committees (and based on earlier studies, we can assume that chief judges were applying the Act properly).3

Obviously, it’s not possible to infer the number of complaints likely to be presented to the proposed committee about the nine active status and three senior status justices, but it seems reasonable to assume a manageable number of unmeritorious complaints, and a handful of complaints meriting the committee’s attention.

What kind of “enforcement”?

Kagan talked about “enforcing” the “rules” in the Court’s code, and referred, without naming any, to “sanctions [that] would be appropriate for violations of our rules.” It’s hard to see how, without statutory authorization, such a committee could impose restrictions on justices’ behavior, such as the temporary suspension of case assignments that the Judicial Conduct Act authorizes for federal judges, or the more extensive sanctions that some state judicial conduct commissions impose, unrestricted by the federal constitutional protections of life tenure and irreducible salaries.

Rather than the state judicial conduct commissions or the federal judicial councils, Kagan’s proposal might be better analogized—but with two big differences —to the Judicial Conference Codes of Conduct Committee, which provides advice to judges (and justices) contemplating actions that might contravene the code.

The differences: Questions would come to the Kagan-proposed committee from complainants, and its responses, at least to non-frivolous complaints, would not be advisory and confidential but rather dispositive and likely public, belying one critic’s complaint that it “would achieve nothing.” A committee finding that a justice had committed misconduct would be the equivalent of the public “censure” or “reprimand” that the Conduct Act authorizes.

For that matter, the committee could also, as the judicial councils are authorized, recommend possible reference to the House of Representatives for possible impeachment. But even a mild rebuke is something any justice would want to avoid.

Standards for assessing misconduct

Kagan described such a committee as reviewing allegations of “violations of the rules” in the Code. In fact, the Code is a mixture of specific rules and general admonitions. The Code’s “commentary” says as much; some “Canons provide fairly specific guidance,” such as the ban on testifying voluntarily as character witnesses, but in “many cases [the] Canons are broadly worded general principles informing conduct, rather than specific rules requiring no exercise of judgment or discretion. It is not always clear, for example, whether particular conduct undermines, promotes, or has no effect on ‘public confidence in the integrity and impartiality of the judiciary’…”

The difficulty of adjudicating violations of well-taken generalizations is why most codes of conduct themselves don’t have enforcement mechanisms, or at least specify which provisions are subject to disciplinary review and which are advisory. Rather than charge the Kagan-proposed committee with determining misconduct by assessing violation of the “rules,” the Court might charge it with a task similar to that in the 1980 Judicial Conduct Act. The Act’s standard for judging misconduct is not whether a lower court judge violated the judiciary’s code of conduct but rather whether the judge’s conduct was “prejudicial to the effective and expeditious administration of the business of the courts.” The code of conduct can sometimes provide guidance as to what behavior falls within the general standard, but that is not the same as saying any violation of the code is misconduct.

Recusal

Many of the Court’s Code’s specific “rules” relate to recusal and disqualification. Canon 3.B is essentially the justices’ collective interpretation of how they should apply the judicial disqualification statute to themselves. Much of the published or reported commentary on Kagan’s proposal (the Wall Street Journal editorial and a single news article) assume that the committee would assess justices’ recusal decisions, but Kagan said nothing to that effect and it would seem odd to assign to an administrative committee a determination of whether a justice correctly applied the law (the recusal statute). The lack of any appellate body to which to appeal a recusal refusal may well be a problem in need of resolution, but the committee Kagan proposed is not it.

Would it work?

The first question is—assuming the chief justice would consider appointing a committee of lower court judges to assess allegations of justices’ misconduct—whether the rest of the Court would agree. As noted above, Kagan spoke only for herself, but as a practical matter the others’ buy-in would be necessary and not necessarily easily obtained. It took several years of pressure to produce the Code published last November.

The selling point would be, as Kagan put it, that the committee “would also benefit us in various kinds of ways because it would provide a kind of safe harbor” from unfounded allegations. “Sometimes people accuse us of misconduct where we haven’t engaged in misconduct.”

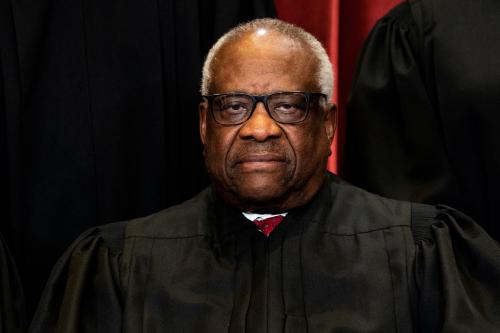

The second question is whether lower court judges with the qualities Kagan identified—respected, experienced, and with a reputation for fairness—are also willing to let the chips fall where they may. Most federal judges’ attitudes toward the Court are characterized, understandably, by a deep reservoir of what political scientists call “diffuse support” —support for the institution and its role even among those having little “specific support” for the Court’s policies. That leads to reluctance to speak candidly, in public, about the justices. Thus, the problem with Kagan’s proposal is probably not what the Wall Street Journal called “political pressure to rule against this or that Justice” but rather a reluctance to do so, out of deference to the institution. (The Judicial Conference’s Financial Disclosure Committee’s recently released March 2024 report of its “ongoing review of public written allegations of errors or omissions in a filer’s [i.e., Justice Thomas’s] financial disclosure reports” denotes a year-long-and-counting investigation, which may reflect the complexity of the matter, or a quandary among federal judges over how to deal with problematic Supreme Court behavior.)

To sum up, Kagan has offered a suggestion that, while modest, is probably unnerving to at least some members of the Court. And many details of its operation are unresolved. But it may invigorate the debate over how to police the Court, a debate that has been largely unproductive so far.

-

Footnotes

- Starting at about minute 45:37.

- At subsection (h) (2).

- Complaint data and bankruptcy and magistrate numbers based on tables S-22, 11 and 12 of the latest report of federal judicial statistics. Sitting life-tenured judges derived from Federal Judicial Center data.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Fleshing out Justice Kagan’s modest idea for Supreme Court ethics enforcement

August 21, 2024