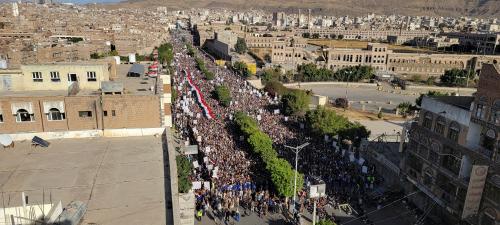

As the world has focused on the Russian invasion of Ukraine, rightly, the war in Yemen is entering its eighth year. Saudi Arabia has completely failed in its campaign to defeat the Zaydi Shia Houthi rebels, who control the capital, Sana’a, most of northern Yemen, and 80% of the population. The Yemeni people are paying a horrific price from the war which has no end in sight.

The Saudi intervention in Yemen has many similarities to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Like the Russians, the Saudis greatly underestimated their opponents. The Saudi mission was initially code-named Operation Decisive Storm; it is anything but decisive. In 2015, its architect, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (a.k.a. MBS) told then-Central Intelligence Agency Director John Brennan that the Houthis would be toppled in a matter of a few weeks. As Brennan notes in his memoirs, he wondered what MBS “was smoking.” The Saudi ground forces never even got close to Sana’a. They seemed to assume the rebels would be defeated with air power, a badly flawed strategy.

Unlike Ukrainians, more than 3.6 million of whom have fled the country to neighbors like Poland and Moldova in the past month, few average Yemenis can flee the war to refuge outside the country. There are many internally displaced persons, however, who have lost their homes — more than 3.6 million as of December 2020. Poverty is acute.

The partial Saudi blockade of Yemen has led to a massive humanitarian catastrophe. Yemen imports most of its food and medicine. According to the World Food Program, at least half of Yemeni children under the age of five — 2.3 million people — are at acute risk of malnutrition. The United Nations estimates 377,000 deaths in seven years, the vast majority from malnutrition and related causes. With the war in Ukraine blocking exports of grain from the two combatants, which together make up a third of global wheat exports, food prices are going up, and the poorest country in the Arab world will suffer.

The blockade also prevents fuel from getting into the country. By one estimate, Yemen is getting only one tenth of the fuel it imported before the war. This impacts on the already weak health and education infrastructure.

The Houthis continue to take the war to the Saudis by firing missiles and drones at targets in the kingdom. Most of the targets are in the border area near Yemen, but the Houthis also strike Riyadh and other cities. Earlier this month they attacked a refinery in the Saudi capital; last Sunday they launched a wave of attacks including on oil installations. So far the damage has been small, but one shot could injure hundreds of people if it hits a crowded place like an airport lounge or a hotel.

The Houthi strikes are far fewer than the Saudi air strikes in Yemen. The Saudis have launched almost 25,000 air strikes in seven years while the Houthis have fired fewer than 1,300 missiles and drones in the same period.

The rebels have not resumed their attacks on the United Arab Emirates, which I wrote about last month. The Emiratis withdrew the Giants Brigade, a Yemeni militia they fund, from the frontline with the Houthis, effectively caving to their demands. Last week, Dubai received Syrian President Bashar Assad in an apparent step at rehabilitating the dictator. It is the first time Assad has been welcomed in an Arab country since the Syrian civil war began in 2011. Syria and Iran are the Houthis’ only state allies.

There is one crucial difference between the war in Ukraine and the war in Yemen. The Houthis are not a democratically-elected government. They are serial human rights abusers. They have rallied support and sentiment behind them because of the invasion and blockade from Yemen’s historic enemy, Saudi Arabia. They have included other parties and leaders in their government, but they are not democrats.

In the Ukraine war the Houthis have tilted toward Russia, but they have nothing to offer Moscow. Along with Damascus, they recognized the independence of the two Russian-created rebel states in eastern Ukraine. They have blamed Kyiv — and in particular, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s Jewishness — for the war. The intense anti-American ideology of the Houthis, reinforced by seven years of being bombed by American-made aircraft with American munitions, probably explains the decision to appease Moscow. Russia has also been a longtime critic of the one-sided United Nations Security Council resolution that tilts toward the Saudis and was pushed through the council by Washington in 2015. It was renewed last month.

The world is right to be focusing on Ukraine: As President Joe Biden says, it could pave the way to World War III, which must be avoided. As someone who helped build the Operation Southern Watch no-fly zone in Iraq in August 1992 from the National Security Council staff, I agree fully that a no-fly zone in Ukraine is a declaration of war with Russia.

But we should also make every effort to end the war in Yemen, as Biden promised a year ago. The immediate step is to end the blockade which causes so much damage to the most vulnerable, the children of Yemen who need America’s help and protection.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Yemen war turns seven

March 24, 2022