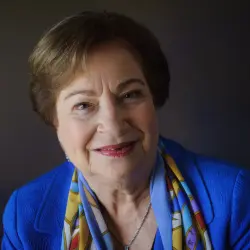

In the aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union, the United States sought to integrate the new Russia into Euro-Atlantic and global institutions, writes Angela Stent. That didn’t work, she argues. The next U.S. president needs to redouble efforts to ensure that Russia does not thwart America’s commitment to create a peaceful, rules-based post-Cold War order. This piece originally appeared in the Washington Post.

It’s been a quarter-century since the Soviet Union collapsed. In the aftermath, the United States had two main goals: The first was integrating the new Russia into Euro-Atlantic and global institutions; the second, if that did not work out, was ensuring that Russia not thwart America’s commitment to create a peaceful, rules-based post-Cold War order. A quarter-century later, it is clear that the first goal was not achieved. That means the next occupant of the White House will have to redouble efforts to achieve the second.

The Russia challenge has radically changed since the 1990s. Today we read new allegations that Russia is interfering in the U.S. election, hacking into the Democratic National Committee and, through intermediaries, posting confidential and sometimes damaging information. Whatever the accuracy of these charges and scope of these disclosures, they seem clearly intended to sow doubts about the legitimacy of our democratic election process. From the Kremlin’s point of view, the more uncertainty and questioning the better.

How should the United States respond? First, we need to understand the domestic motivations for Russia’s actions. Recent shakeups in top leadership—most notably the firing of Vladimir Putin’s longtime aide Sergei Ivanov and the creation of Putin’s own Praetorian Guard to protect him both from a “color” revolution and a palace coup—suggest that the president remains focused on ensuring that the September elections to the Russian Duma and his own re-election in 2018 are carefully managed to prevent a repetition of 2011, when tens of thousands of Muscovites took to the streets to protest what people believed were falsified elections results. Putin blamed Hillary Clinton for the demonstrations.

Since then, Russia’s economic situation has deteriorated because of economic mismanagement, falling oil prices and Western sanctions imposed after the Crimean annexation. But the Kremlin has skillfully played a weak hand by appealing to patriotism. It blamed the United States for Russia’s economic problems and launched an air campaign in Syria last September that forced the United States to negotiate and recognize its enhanced international role.

Faced with a Kremlin that defines the United States as its main adversary, how should the next U.S. president approach Russia? She or he should not seek another “reset” but accept the fact that the Russia we are dealing with today requires a different approach. Engagement for engagement’s sake does not work.

The United States should continue negotiating with Russia over both Syria and Ukraine, but it should only open an intensified dialogue with the Kremlin if and when the Russian leadership is genuinely interested in offering constructive proposals. The gap between U.S. and Russian interests in both cases is significant.

As long as Russia supports the conflict in eastern Ukraine that has already claimed 10,000 lives, U.S. sanctions should remain in place. The United States should consider enhancing its own military presence in Europe and needs to deter any further attempts by Russia to destabilize its neighboring countries. The Russia challenge is long-term and will likely outlast both the next U.S. president’s term and Putin’s time in office.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Why there will be no “reset” with Russia

August 22, 2016