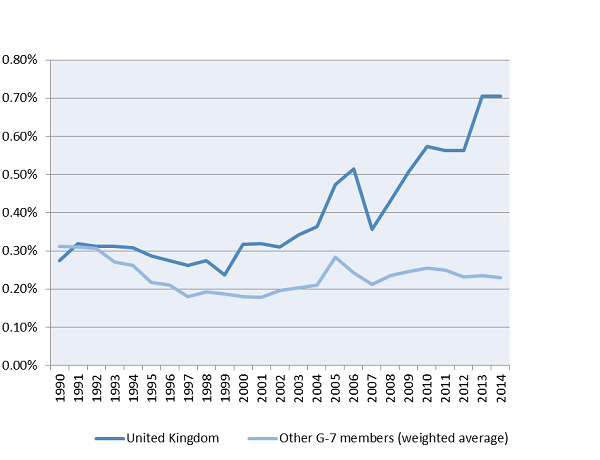

With elections in the United Kingdom now over, the public have returned a majority Conservative government—and over the same night we have seen huge changes in our political landscape. But one thing is pretty certain: the U.K.’s status as the only G-7 donor ever to deliver the U.N. 0.7 percent target for official development assistance (ODA) is not in doubt. The U.K. reached the target of 0.7 percent of GNI for aid in 2013.

Since the U.N. target was established in 1970, just seven donors have met it. Norway, Denmark, and Sweden have mostly exceeded 0.7 percent since 1975; the Netherlands did so until 2013 and Luxembourg since 2000. Finland hit the target once in 1991. And now the United Kingdom has for two years. So how has this been achieved?

Figure 1. Official Development Assistance as a percentage of Gross National Income, 1990-2014

Source: Development Initiatives, based on OECD data

Public support in the U.K. for helping people in other countries has long been high in polls. But it is a mistake to think that public opinion has been the crucial factor in getting the U.K. to 0.7 percent.

Opinion polls in 1988, 1989, 1991, and 1992 put U.K. support for aid at 71 percent, 72 percent, 85 percent, and 75 percent respectively. But this support did not prevent a decline in U.K. aid from 0.51 percent of GNI in 1979 to 0.31 percent in 1993. Similarly, public support for aid in Norway rose from 77 percent to 84 percent between 1990 and 1993, but over the same period Norwegian aid fell from 1.17 to 1.01 percent of GNI.

So if public opinion has not been the crucial factor underpinning the U.K.’s historic achievement, what has? The answer is that one ingredient has been key: political leadership. And leadership at the highest level.

It was in 2004 under a Labour government led by Tony Blair, with Gordon Brown as chancellor of the exchequer and Secretary of State Hilary Benn, that the U.K. set a timetable to reach 0.7 percent by 2013. U.K. aid in 2004 stood at 0.36 percent, rising to 0.57 percent by the time Labour left office. In 2009, the opposition Conservative Party led by David Cameron pledged: “If elected, a new Conservative Government will be fully committed to achieving, by 2013, the U.N. target of spending 0.7 percent of national income as aid.”

Despite the austerity facing all OECD countries, the Conservative-led government and Liberal Democrat coalition partners, (with their longstanding commitment to the U.N. target), have delivered on this pledge. The outgoing government protected just two areas of spending from budget cuts designed to reduce debt after the 2008 crash: health and international development.

So will the U.K. stick to 0.7 percent and are there lessons for others?

Of course politicians and governments in many other countries over many years have set a course for 0.7 percent. But the record shows how often they have been blown off-course by an election or economic headwinds. During the election campaign, four mainstream parties (Conservative, Labour, the Liberal Democrats, and the Scottish National Party) endorsed the U.K. commitment. And in 2015 the U.K. Parliament enshrined in legislation the commitment to keep aid at this level.

The political leadership both builds on and is underpinned by three decades of investment in global education—teachers helping young people understand local-to-global linkages and interdependence. The U.K.’s very strong civil society sector has nurtured public and political support through awareness-raising, fundraising, and campaigns such as Make Poverty History. Since Live Aid in 1985, the entertainment industry and more recently major corporations have also helped to manifest an often invisible but widespread public engagement.

But there are signs of something deeper too.

Canvassing for the election, a local Conservative candidate campaigning in my village, Evercreech in Somerset, deployed three powerful arguments when the question of why we are spending $19.4 billion on aid came up on the doorstep:

- “It’s the right thing to do.”

- “It’s in our interests.”

- “It’s just who we are.”

The moral argument was front and center. Second was enlightened self-interest—recognizing the mutual benefits in trade and stability that translate into security and prosperity. But it is the third answer that is most intriguing.

Who would have expected to see a British foreign secretary making the campaign against female genital mutilation a personal, a governmental, and a Foreign Office priority? Or expected the U.K. Home Office to be focused, as it is, on issues of human trafficking? Fair trade has gone from being caricatured as a preoccupation of the “beards and sandals brigade” to goods on the shelves of every supermarket.

The U.K. has changed. It has become more diverse and more inclusive. It is emerging from the uncertainties and hang-ups of the post-colonial, post-war era. It is adjusting to the necessity of soft power and the potential advantages in terms of diplomacy, trade, and security; and it is recognizing the reality of shared global challenges and the political returns of delivering on commitments.

In September, world leaders will agree on a new set of universal and sustainable development goals to be reached by 2030. The United Kingdom government’s approach to those negotiations should reflect these changes and a country less stuck in the narrative of the last 50 years, and more focused on the opportunities of the next 15.

***Note: This blog was updated on May 8, 2015 at 9:30 a.m. EST to better incorporate the final election results.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Why the new UK government will stick to its commitments on aid

May 8, 2015