The rapid spread of digital technologies has been a development success. But has it also resulted in successful development? No, not when the basic foundations of economic development are missing, argues the World Development Report 2016: Digital Dividends.

Increased prosperity and our incessant desire to stay connected have contributed to the rapid spread of digital technologies. More households in developing countries own a mobile phone than have access to electricity or clean water. Nearly 70 percent of the bottom-fifth of the population in developing countries own a mobile phone. The number of Internet users has more than tripled in the last decade—from 1 billion in 2005 to an estimated 3.2 billion at the end of 2015.

The digital revolution has brought immediate private benefits—easier communication and information, greater convenience, free digital products, and new forms of leisure. It has also created a profound sense of social connectedness and global community.

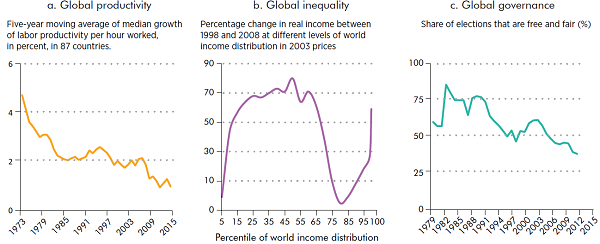

But despite great expectations—and frequent claims—of transformational impacts, the broader benefits of higher growth, more jobs, and better services have fallen short. Firms are more connected than ever before, but global productivity growth has been stagnant. Digital technologies are making workers more productive, but at the same are “hollowing out” the middle class, particularly in the wealthier countries. And while the Internet was expected to spread democracy and liberty around the world, the unfortunate reality is that the share of elections that are free and fair is falling (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Digital technologies have spread rapidly, but digital dividends have lagged behind

Source: World Development Report 2016: Digital Dividends

.

Wael Ghonim, who played an instrumental role in triggering the Arab Spring in his home country of Egypt, said in 2011, “If you want to liberate a society, all you need is the Internet.” In 2016, having witnessed both the strengths and shortcoming of social media, he retracted his earlier comments: “I was wrong….Today, I believe if we want to liberate society, we first need to liberate the Internet.”

Why is the Internet, with its ability to dramatically transform our economy, society, and politics, failing to live up to its potential? To paraphrase Bill Clinton’s 1992 presidential campaign, it’s the analog complements, stupid!

For too long, the world has succumbed to a simplistic theory that greater connectivity equates to faster development. This theory had a credible beginning. As the Internet spread from the United States to the rest of the advanced economies in the 1990s, most of its early adopters were skilled professionals, living in countries with an enabling business environment, and governed by accountable politicians. When the Internet became accessible, they put it to good use: Firms, incentivized by competition, used technology to explore innovative business practices, skilled workers exploited technology to become more productive, and accountable governments deployed technology to address citizens’ needs. The techno-optimists among us felt vindicated, equating the spread of the Internet with faster growth, more jobs, and better services. But had they looked deeper, they would have noticed that the transformation brought about by technology was conditional on the presence of three complements: a favorable business climate, strong human capital, and good governance.

The link between technology and development grew more tenuous over time. As the digital revolution forged ahead, almost everyone had access to the technology, but many lacked the necessary complements. So in the hands of unaccountable governments, the Internet was no more a platform for development, but a tool for state control and elite capture. When workers lacked skills, technological progress did not translate to more jobs but to greater automation. And in the presence of vested interests and a poor business climate, technology was monopolized by entrenched incumbents, limiting entry of disruptive startups and innovative business models. Not surprisingly, connectivity without complements produced disappointing development outcomes.

What, then, should we do? Dropping the rhetoric that connectivity is sufficient to accelerate development will be a good start. The harder task is to continue to build a strong analog foundation to make the Internet work for everyone—by strengthening regulations that ensure competition among businesses, by investing in workers’ skills that meet the demands of the new economy, and by ensuring that institutions are accountable. The good news is that the Internet can help, by enabling, and perhaps accelerating, the formation of these analog complements.

Editor’s Note: To read the

World Development Report 2016:

Digital Dividends and to see how technology is transforming the lives of people from China to India, click here

.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Why have the digital revolution’s broader benefits fallen short for development?

January 28, 2016